1. The Stage is Set:

“Whence came the European seemed to disturb them (the Osages) very little. He was an off-brand whom they had not seen before who came paddling up the river. He was not one of them, then he was a potential enemy, even if not at the moment. But he was of breath stopping interest to them. When they first saw him, they had no idea that this pale, hairy man would later overrun their domain …”

John Joseph Mathews “The Osages - Children of the Middle Waters, 1961

“Whence came the European seemed to disturb them (the Osages) very little. He was an off-brand whom they had not seen before who came paddling up the river. He was not one of them, then he was a potential enemy, even if not at the moment. But he was of breath stopping interest to them. When they first saw him, they had no idea that this pale, hairy man would later overrun their domain …”

John Joseph Mathews “The Osages - Children of the Middle Waters, 1961

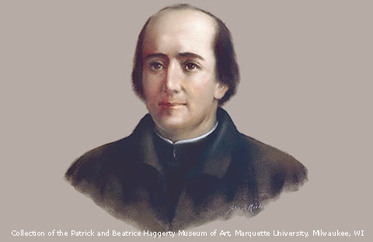

Father Jacques Marquette

Father Jacques Marquette

John Joseph Mathews said it was sometime in the mid to late seventeenth century when two Europeans paddled a canoe into the Osages’ awareness. They were immediately a curiosity and not entirely pleasant. The Osages had very little body hair, bathed and in warm weather, dressed lightly. The “Heavy Eyebrows” were covered with body hair, even on their backs and hands. Their eyes and mouths were nearly covered with hair. Their mouths, and remaining teeth, resembled the den of an old beaver overhung with roots. The Heavy Eyebrows wore sweat-stained buckskin shirts, leggings and moccasins and they smelled terrible. Also unsettling was the Europeans interest in their women.

In time the Osages developed some tolerance with their new neighbors. The Europeans kept a stock of beads, blades, scrapers and sparkling things that could be traded for furs. Some of the Heavy Eyebrows were nearly as skilled at hunting and processing game as themselves. Later they were introduced to the wood and metal machine that belched fire, smoke and thunder that could kill. As long as they could keep a distance, the Europeans were tolerable.

In time, relationships formed. But the Osages stayed more distant from the English and Spanish Heavy Eyebrows. They were arrogant—a trait the Indians didn’t entirely understand but disliked. They built strange temples in their villages and practiced ritualistic prayer the Indians didn’t understand. Then, they ridiculed their belief in Wah’Kon-Tah, the center of their own religious life. The Spanish in particular viewed the Osages as one of their worst, but strongest, tribal “problems” which likely increased their arrogance. These visitors were not trusted.

The French were different. They were less arrogant in their dealings with the Indians—or perhaps they were just more shrewd. Both the French and Osages recognized they could augment one another. The French traders wanted furs and the Osages were among their best suppliers. The Osage also exhibited a keen, if not crude, business sense. In addition to trade potential, it just made good sense to schmooze the race of giant people who were a recognized military force in the region.

The French religion was not unlike that of the other Europeans but the French seemed to flaunt it less and accepted the Osages beliefs. The Osages took notice of the French holy men or “Black Robes.” The Jesuit Priests seemed to treat the French, the Indian and area settlers with equal respect. The relationship among the Osages, the French and the Black Robes endured and eventually led many southeast Kansas residents to their homes.

An Important Influence.

If you have to select a single influence that shaped the development of central Missouri and southern Kansas it would be the Osage Nation. They, and the changes they brought, shaped the development of commerce, education, religion and civilization across a broad region. They also put St. Paul, Kansas exactly where it is on the map. Without the Osage people St. Paul would not exist; and some of the older families that came together here during the late 1800’s might not exist.

Why did we end up here? An underlying reason is the government’s persistence in pushing the Indian tribes west, until they could be “civilized.” Events that led the Osage into southern Kansas, and to Osage Mission, follow a series of treaties and a relationship between the Osage, the French and the Jesuits.

Earliest contracts between The Osage and Jesuits.

The earliest mention of an Osage-Jesuit connection is from the journal of Father Jacques Marquette. During his historic voyage down the Mississippi with Louis Jolliet, he visited them in 1673 on the banks of the Osage River and its tributaries in what is today southwestern Missouri. Following his short visit the Osage heard of the works Father Jacques Gravier, S.J., was performing among the Illinois, Peoria's and Kas-Kas-Kias, who under his teaching, had become Christians. At about the end of the 17th century, the Osage requested that Father Gravier visit their villages on the Osage River. Father Gravier agreed to visit them, but he died before he could do so.

There were other brief contacts between the time of the Marquette encounter and the opening of the Osage Catholic Mission. But perhaps the most enduring connection occurred as a result of the Osage relationship with the French.

(Note: There is disagreement as to whether Fr. Marquette actually visited the Osage or was only aware of them. However, his awareness did influence future contacts between the Jesuits and Osages.)

In time the Osages developed some tolerance with their new neighbors. The Europeans kept a stock of beads, blades, scrapers and sparkling things that could be traded for furs. Some of the Heavy Eyebrows were nearly as skilled at hunting and processing game as themselves. Later they were introduced to the wood and metal machine that belched fire, smoke and thunder that could kill. As long as they could keep a distance, the Europeans were tolerable.

In time, relationships formed. But the Osages stayed more distant from the English and Spanish Heavy Eyebrows. They were arrogant—a trait the Indians didn’t entirely understand but disliked. They built strange temples in their villages and practiced ritualistic prayer the Indians didn’t understand. Then, they ridiculed their belief in Wah’Kon-Tah, the center of their own religious life. The Spanish in particular viewed the Osages as one of their worst, but strongest, tribal “problems” which likely increased their arrogance. These visitors were not trusted.

The French were different. They were less arrogant in their dealings with the Indians—or perhaps they were just more shrewd. Both the French and Osages recognized they could augment one another. The French traders wanted furs and the Osages were among their best suppliers. The Osage also exhibited a keen, if not crude, business sense. In addition to trade potential, it just made good sense to schmooze the race of giant people who were a recognized military force in the region.

The French religion was not unlike that of the other Europeans but the French seemed to flaunt it less and accepted the Osages beliefs. The Osages took notice of the French holy men or “Black Robes.” The Jesuit Priests seemed to treat the French, the Indian and area settlers with equal respect. The relationship among the Osages, the French and the Black Robes endured and eventually led many southeast Kansas residents to their homes.

An Important Influence.

If you have to select a single influence that shaped the development of central Missouri and southern Kansas it would be the Osage Nation. They, and the changes they brought, shaped the development of commerce, education, religion and civilization across a broad region. They also put St. Paul, Kansas exactly where it is on the map. Without the Osage people St. Paul would not exist; and some of the older families that came together here during the late 1800’s might not exist.

Why did we end up here? An underlying reason is the government’s persistence in pushing the Indian tribes west, until they could be “civilized.” Events that led the Osage into southern Kansas, and to Osage Mission, follow a series of treaties and a relationship between the Osage, the French and the Jesuits.

Earliest contracts between The Osage and Jesuits.

The earliest mention of an Osage-Jesuit connection is from the journal of Father Jacques Marquette. During his historic voyage down the Mississippi with Louis Jolliet, he visited them in 1673 on the banks of the Osage River and its tributaries in what is today southwestern Missouri. Following his short visit the Osage heard of the works Father Jacques Gravier, S.J., was performing among the Illinois, Peoria's and Kas-Kas-Kias, who under his teaching, had become Christians. At about the end of the 17th century, the Osage requested that Father Gravier visit their villages on the Osage River. Father Gravier agreed to visit them, but he died before he could do so.

There were other brief contacts between the time of the Marquette encounter and the opening of the Osage Catholic Mission. But perhaps the most enduring connection occurred as a result of the Osage relationship with the French.

(Note: There is disagreement as to whether Fr. Marquette actually visited the Osage or was only aware of them. However, his awareness did influence future contacts between the Jesuits and Osages.)

Auguste Chouteau

Auguste Chouteau

The French, The Osage and The Jesuits.

Auguste Chouteau was born in New Orleans to a teen-age mother with an abusive husband. When he was fourteen, they fled to the wilderness with Pierre de Laclede, who had gained a monopoly on the trading of furs in the Missouri region. On February 15, 1764, young Chouteau, under Laclede’s direction, supervised the mapping and the layout of first streets of St. Louis. This remote outpost was the headquarters of a company that would eventually handle nearly all the furs collected from the basins of the Missouri, Platte, Osage, and Arkansas Rivers.

Auguste Chouteau was born in New Orleans to a teen-age mother with an abusive husband. When he was fourteen, they fled to the wilderness with Pierre de Laclede, who had gained a monopoly on the trading of furs in the Missouri region. On February 15, 1764, young Chouteau, under Laclede’s direction, supervised the mapping and the layout of first streets of St. Louis. This remote outpost was the headquarters of a company that would eventually handle nearly all the furs collected from the basins of the Missouri, Platte, Osage, and Arkansas Rivers.

Jean Pierre Chouteau

Jean Pierre Chouteau

In 1768 Auguste Chouteau became a full partner in the company and when Laclede died in 1778, he took control. His brother Jean Pierre also took a prominent role in the company and set up several trading posts. Pierre Chouteau’s son, Pierre Jr., followed in the family footsteps and established successful trading posts in Indian Territory and with the Osage. A business partnership with John Astor’s American Fur Company propelled the Chouteau’s to wealth and political influence; and they enjoyed a virtual monopoly with Mississippi region trading. A key ingredient to the Chouteau success was their ability to work well with important suppliers—the Indian tribes along the Mississippi and its tributaries. Among their most reliable suppliers were the Osage of central and western Missouri.

The Osages were good for business. They were skilled hunters and negotiators who exhibited business savvy themselves. Over time, business relationships led to close friendships and eventually marriages. Perhaps most important, the Osage themselves commanded respect. They were physically large; and they had a reputation as being fierce warriors. At the turn of the 19th century the Osage were considered to be the most formidable military and economic force in the region. Even the government was reluctant to confront “the Osage problem.” The Osage knew the white man’s civilization was coming; but they were determined to meet it on their terms!

Another result of the Osage–French bond was a growing acquaintance with the Jesuits. They saw the respect the French held for the priests. They also admired the work the Jesuits did with the French, the local settlers, and the tribes. This admiration became very important later.

The Osages were good for business. They were skilled hunters and negotiators who exhibited business savvy themselves. Over time, business relationships led to close friendships and eventually marriages. Perhaps most important, the Osage themselves commanded respect. They were physically large; and they had a reputation as being fierce warriors. At the turn of the 19th century the Osage were considered to be the most formidable military and economic force in the region. Even the government was reluctant to confront “the Osage problem.” The Osage knew the white man’s civilization was coming; but they were determined to meet it on their terms!

Another result of the Osage–French bond was a growing acquaintance with the Jesuits. They saw the respect the French held for the priests. They also admired the work the Jesuits did with the French, the local settlers, and the tribes. This admiration became very important later.

Fort Osage near present Sibley Missouri is now a national historic site.

Fort Osage near present Sibley Missouri is now a national historic site.

Government Forts with Business Backing.

For the time being the government wanted the Osage to be content and cooperative. This led to the government, working with established fur traders, to establish privately-backed forts or fortified fur trading facilities. These forts provided security and central drop-off and trading spots for the Osage’s furs. They also served to control clashes between the tribes and encroaching white civilization.

One fort was conceived in 1794 when tension between the Osage and white settlements along the Osage River reached an explosive stage. Spanish government officials found it necessary to establish a military fort near a main rendezvous of the Osage. Auguste Chouteau offered to build and maintain a garrison which was placed under the command of his brother, Pierre. He also agreed to pay $2,000 annually, provided he was given a six-year grant of exclusive trade with the Osage. The offer was accepted and Chouteau built Fort Carondelet on a bluff overlooking the principal village of the tribe. The spot is now Halley’s Bluff, Vernon County, Missouri, near present-day Nevada.

In 1804 Meriwether Lewis and William Clark noted another potential spot on a high vantage point along the Missouri River near present day Sibley Missouri, or just east of Independence. At about the same time Pierre Chouteau, and an agent for the Osages, met with President Thomas Jefferson about the possibility of building a trading post and fur processing facility in the same area. A fur factory at this location would provide the Osage with a lucrative drop-off point for their furs; and would pacify the tribe’s restlessness. In 1808, under the leadership of William Clark, Fort Osage was built on the high river bluff he previously visited. Fort Osage and the work of the Chouteau’s seeded present-day Kansas City; and it is now a national historic site.

The Stage is Set.

At this point, the Chouteau–Osage relationship and the Government’s need to handle the Indian problem set the stage for change and a westward movement. Also, the principle players were already familiar with the territory west of the Missouri-Arkansas lines.

All that was needed to get things moving was stimulus.

For the time being the government wanted the Osage to be content and cooperative. This led to the government, working with established fur traders, to establish privately-backed forts or fortified fur trading facilities. These forts provided security and central drop-off and trading spots for the Osage’s furs. They also served to control clashes between the tribes and encroaching white civilization.

One fort was conceived in 1794 when tension between the Osage and white settlements along the Osage River reached an explosive stage. Spanish government officials found it necessary to establish a military fort near a main rendezvous of the Osage. Auguste Chouteau offered to build and maintain a garrison which was placed under the command of his brother, Pierre. He also agreed to pay $2,000 annually, provided he was given a six-year grant of exclusive trade with the Osage. The offer was accepted and Chouteau built Fort Carondelet on a bluff overlooking the principal village of the tribe. The spot is now Halley’s Bluff, Vernon County, Missouri, near present-day Nevada.

In 1804 Meriwether Lewis and William Clark noted another potential spot on a high vantage point along the Missouri River near present day Sibley Missouri, or just east of Independence. At about the same time Pierre Chouteau, and an agent for the Osages, met with President Thomas Jefferson about the possibility of building a trading post and fur processing facility in the same area. A fur factory at this location would provide the Osage with a lucrative drop-off point for their furs; and would pacify the tribe’s restlessness. In 1808, under the leadership of William Clark, Fort Osage was built on the high river bluff he previously visited. Fort Osage and the work of the Chouteau’s seeded present-day Kansas City; and it is now a national historic site.

The Stage is Set.

At this point, the Chouteau–Osage relationship and the Government’s need to handle the Indian problem set the stage for change and a westward movement. Also, the principle players were already familiar with the territory west of the Missouri-Arkansas lines.

All that was needed to get things moving was stimulus.

Go to: 2. The Osages Enter Kansas - or - Story

Some Reference Information:

- A History of the Osage People, Louis F. Burns, 1989

- Beacon on the Plains, Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald, 1938

- Getting Sense – The Osages and Their Missionaries, James D. White, 1997

- St. Louis Catholic Historical Review, Quarterly Issue of January - April 1922, Rev. John Rothensteiner

- The Osage – Children of the Middle Waters, John Joseph Mathews, 1981

- Drawing of Fort Osage and additional information about the fort – From Graphical Fine Arts Press - http://www.epsi.net/graphic/osage.html

- American Journeys, Eyewitness Accounts of Early American Exploration. http://www.americanjourneys.org/aj-126/summary/

- Legends of America, The Chouteau's Early American Traders. http://www.legendsofamerica.com/we-chouteaus.html

- Encyclopedia of the Great Planes, Chouteau, Pierre, Jr. (1789- 1865) http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.ind.012