6. The Early Days – Progress and Tragedy.

“The Jesuits and Sisters of Osage Mission, probably more than any other outside factor, were responsible for the survival of the Osage people. It is no small wonder that eighty percent of the Osages are still Catholic today. These dedicated souls accomplished more than they lived to realize. Their Influence on the souls and aspirations of the Osage people is still present today.”

Louis F. Burns, A History of the Osage People, 1989

“The Jesuits and Sisters of Osage Mission, probably more than any other outside factor, were responsible for the survival of the Osage people. It is no small wonder that eighty percent of the Osages are still Catholic today. These dedicated souls accomplished more than they lived to realize. Their Influence on the souls and aspirations of the Osage people is still present today.”

Louis F. Burns, A History of the Osage People, 1989

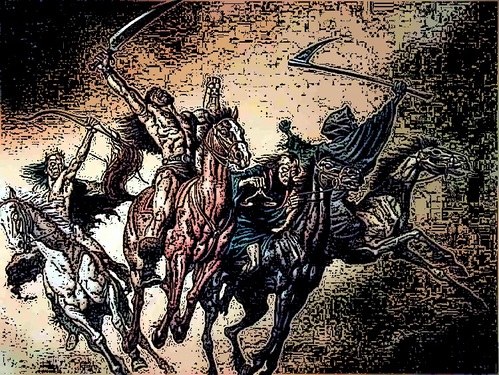

In Part Four of his book, Louis Burns positions the Mission and the missionaries as the main line of defense between the Osages and what he describes as the Four Horsemen, or extinction. His comparison is related to his adaptation of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse of the Book of Revelation. There are various interpretations of this part of the New Testament; particularly with the rider of the white horse. But in general: War rode a red horse; Famine was on a black horse and Death or pestilence rode the pale horse. The white horse has been described as a warrior god (perhaps Christ), the anti-Christ, or conquest. Together, the four horsemen represent events that will occur as mankind approaches the end times. His analogy suggests that when the Osages turned to the religion of the Black Robes, their sovereign being, Wa Kon Ta, was angered and unleashed the horsemen to judge and punish them.

It is interesting that Burns suggests the Black Robes, might have contributed to the mythical onslaught; but as the Osages protectors, he holds them in esteem. But the analogy related to war, famine, and death and the near-apocalypse of the Osage nation, during the period of 1850 through 1870, is hauntingly appropriate.

It is interesting that Burns suggests the Black Robes, might have contributed to the mythical onslaught; but as the Osages protectors, he holds them in esteem. But the analogy related to war, famine, and death and the near-apocalypse of the Osage nation, during the period of 1850 through 1870, is hauntingly appropriate.

It Wasn’t All Bad.

In addition to the Mission and missionaries, the Osages had another powerful influence in their favor. During the period of 1849 through 1861 Major Andrew J. Dorn served as the Osage’s agent with the government. Agent Dorn was in charge of the Neosho Agency and he also became a close friend of Father Schoenmakers. Both held the Osages interests in their hearts. Dorn has been described as one of the most honest and highly esteemed of the government’s agents. In his capacity he did all he could to process the Osages annuity payments, oversee improvements at the mission and act as the official cheerleader for the mission schools with the government. He also worked tirelessly to see that the Osages got desperately needed medical care during the terrible 1850’s. According to Burns, in Dorn’s decade as agent, not one complaint was lodged against him.

With Dorn’s support the missionaries saw sporadic, if not steady, improvements with their assignment. Perhaps most important, they gained the trust of parents who readily sent their youth to the schools. The young Osage proved themselves to be as capable as any white student in the classrooms. But attempts to teach farming to the Osage were marginally successful. Initially the Indians approach to agriculture was to till the soil; plant the seeds and then abandon the plots. They had watched plants grow on their own for decades and saw no reason to abandon hunting interests to watch dirt. However, Father Schoenmakers was successful in paying some of the Osage boys to maintain small plots and the interest grew into about twenty-five farm plots by 1855.

Also important was the Jesuit’s acquaintance with the fur traders. Instead of the antagonistic relationship that Protestant predecessors, like Benton Pixley, had churned; the Chouteau’s and other traders were friendly with the Jesuits. They might not have supported the attempts to agriculturize the Osage but they permitted it—they probably didn’t think it would work anyway.

Success with converting the Osage was also mixed. The mission staff was small and their efforts were divided among teaching, farming, medical care, the church and administrative tasks. The full-blood Indians would grasp the religion and submit to the authority of the missionaries. But trying to keep them engaged, with their nomadic lifestyle, was difficult. Many of the mixed-blood Osages were French Canadians who had been baptized. They clung tenaciously to the Catholic Faith, but knew practically nothing about it. In one of his Annual Letters Father Ponziglione penned his discouragement:

“It is difficult at this Mission among the Osage to write annual letters for there are but few things worthy of notice. From the very beginning of this mission in 1847 to the present very little was accomplished …..”

The mission had made real progress but there was reason for discouragement—especially for the Osage.

In addition to the Mission and missionaries, the Osages had another powerful influence in their favor. During the period of 1849 through 1861 Major Andrew J. Dorn served as the Osage’s agent with the government. Agent Dorn was in charge of the Neosho Agency and he also became a close friend of Father Schoenmakers. Both held the Osages interests in their hearts. Dorn has been described as one of the most honest and highly esteemed of the government’s agents. In his capacity he did all he could to process the Osages annuity payments, oversee improvements at the mission and act as the official cheerleader for the mission schools with the government. He also worked tirelessly to see that the Osages got desperately needed medical care during the terrible 1850’s. According to Burns, in Dorn’s decade as agent, not one complaint was lodged against him.

With Dorn’s support the missionaries saw sporadic, if not steady, improvements with their assignment. Perhaps most important, they gained the trust of parents who readily sent their youth to the schools. The young Osage proved themselves to be as capable as any white student in the classrooms. But attempts to teach farming to the Osage were marginally successful. Initially the Indians approach to agriculture was to till the soil; plant the seeds and then abandon the plots. They had watched plants grow on their own for decades and saw no reason to abandon hunting interests to watch dirt. However, Father Schoenmakers was successful in paying some of the Osage boys to maintain small plots and the interest grew into about twenty-five farm plots by 1855.

Also important was the Jesuit’s acquaintance with the fur traders. Instead of the antagonistic relationship that Protestant predecessors, like Benton Pixley, had churned; the Chouteau’s and other traders were friendly with the Jesuits. They might not have supported the attempts to agriculturize the Osage but they permitted it—they probably didn’t think it would work anyway.

Success with converting the Osage was also mixed. The mission staff was small and their efforts were divided among teaching, farming, medical care, the church and administrative tasks. The full-blood Indians would grasp the religion and submit to the authority of the missionaries. But trying to keep them engaged, with their nomadic lifestyle, was difficult. Many of the mixed-blood Osages were French Canadians who had been baptized. They clung tenaciously to the Catholic Faith, but knew practically nothing about it. In one of his Annual Letters Father Ponziglione penned his discouragement:

“It is difficult at this Mission among the Osage to write annual letters for there are but few things worthy of notice. From the very beginning of this mission in 1847 to the present very little was accomplished …..”

The mission had made real progress but there was reason for discouragement—especially for the Osage.

Maybe the horsemen were unleashed around 1850 ... or before.

Maybe the horsemen were unleashed around 1850 ... or before.

Problems …. Serious Problems.

It seems as though the horsemen were unleashed in about 1850.—or maybe Wa Kon Ta had been angered even earlier than that.

The Pale Horse Rider – Pestilence and Death. An unpleasant by-product of compressing a nomadic culture into a reservation is sanitation. As people settled into villages, and wandered less, disease became more prevalent. As early as 1830 there were reports of influenza epidemics that took the lives of “hundreds” of Osage. In 1833 and 1834 alternate flooding and drought took an initial toll. Then, by summer of 1834, the Osage and other Plains nations were in the grip of a cholera epidemic. 300 to 400 Osage died. By the beginning of 1852 scurvy had become widespread. Then measles broke out that spring. More than ½ of the Osage children and many adults died. It was reported than more than 800 Osage died and some estimates were higher. It was during this period that Father John Bax worked himself to exhaustion trying to treat and baptize as many of his flock as he could. On August 5, 1853 he himself died of scurvy at the infirmary in Fort Scott. He was 35 years old.

In 1855 and 1856 smallpox and scrofula epidemics killed a reported 500 more Osages. According to Louis Burns’ tabulation pestilence took the lives of more than 2,500 Osages during the period of 1829 to 1856.

The Black Horse Rider – Famine. Death tolls related to famine are difficult to quantify because hunger is accompanied by diseases. Without modern crop-management and irrigation, crop failure was common. In addition to the flood-drought cycle of 1833 and 1834; two significant famine periods were recorded. In 1834 grasshopper infestation not only destroyed crops, but wigwams were invaded and food stores were destroyed. In 1860 a severe drought led to food shortages that affected both the Osages and settlers. This drought compounded the tensions of the border strife that led to the Civil War.

The Red Horse Rider – War. The white man’s war compounded the Osages problems and nearly brought an end to the Mission. A separate segment has been set aside which has been linked here.

It seems as though the horsemen were unleashed in about 1850.—or maybe Wa Kon Ta had been angered even earlier than that.

The Pale Horse Rider – Pestilence and Death. An unpleasant by-product of compressing a nomadic culture into a reservation is sanitation. As people settled into villages, and wandered less, disease became more prevalent. As early as 1830 there were reports of influenza epidemics that took the lives of “hundreds” of Osage. In 1833 and 1834 alternate flooding and drought took an initial toll. Then, by summer of 1834, the Osage and other Plains nations were in the grip of a cholera epidemic. 300 to 400 Osage died. By the beginning of 1852 scurvy had become widespread. Then measles broke out that spring. More than ½ of the Osage children and many adults died. It was reported than more than 800 Osage died and some estimates were higher. It was during this period that Father John Bax worked himself to exhaustion trying to treat and baptize as many of his flock as he could. On August 5, 1853 he himself died of scurvy at the infirmary in Fort Scott. He was 35 years old.

In 1855 and 1856 smallpox and scrofula epidemics killed a reported 500 more Osages. According to Louis Burns’ tabulation pestilence took the lives of more than 2,500 Osages during the period of 1829 to 1856.

The Black Horse Rider – Famine. Death tolls related to famine are difficult to quantify because hunger is accompanied by diseases. Without modern crop-management and irrigation, crop failure was common. In addition to the flood-drought cycle of 1833 and 1834; two significant famine periods were recorded. In 1834 grasshopper infestation not only destroyed crops, but wigwams were invaded and food stores were destroyed. In 1860 a severe drought led to food shortages that affected both the Osages and settlers. This drought compounded the tensions of the border strife that led to the Civil War.

The Red Horse Rider – War. The white man’s war compounded the Osages problems and nearly brought an end to the Mission. A separate segment has been set aside which has been linked here.

Side-Notes:

Louis Burn’s introduction quote notes that the Osages have maintained a strong loyalty to the Catholic Faith and especially Father John Schoenmakers. Two things illustrate their admiration of Father John:

Also, to say the Osages have maintained loyalty with traditional Catholicism is not entirely accurate. Many have blended their Catholic faith and ritual with traditional Native American Ritual. According to James D. White in “Getting Sense – The Osages and Their Missionaries” Their Catholicism has evolved over time and continues to evolve (See the note in “Sources”).

Louis Burn’s introduction quote notes that the Osages have maintained a strong loyalty to the Catholic Faith and especially Father John Schoenmakers. Two things illustrate their admiration of Father John:

- Before the Osage Manual Labor Schools, the Osage had no written language. Their written language was developed after 1847. As they developed their dictionary they had no word for “priest.” The current Osage word for priest is “Shouminka” {šǫmįhka (variants šǫmįʾhke, šǫmį'hka) [After an early Catholic missionary named Father Schoenmakers] —a partial definition from the Osage Language Dictionary.}

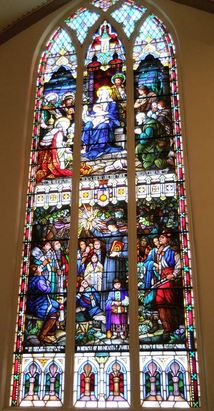

- The Immaculate Conception Catholic Church in Pawhuska, Oklahoma is also known as “The Cathedral of the Osage.” A thirty-six foot tall window in the north transcript of this church is known as the “Osage Window.” The window depicts Father Schoenmakers with a group of Osage adults and children. The parishioners had to request permission, from the Vatican, to install this window because it did not depict a saint, and some of the people illustrated were living Osage.

Also, to say the Osages have maintained loyalty with traditional Catholicism is not entirely accurate. Many have blended their Catholic faith and ritual with traditional Native American Ritual. According to James D. White in “Getting Sense – The Osages and Their Missionaries” Their Catholicism has evolved over time and continues to evolve (See the note in “Sources”).

Go to: 7. The Missionary Trails From Osage Mission - or - Story

Some Reference Information:

- A History of the Osage People by Louis F. Burns, CIGA press, 1989

- Beacon on the Plains, Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald, 1939 (Reprinted by the Osage Mission Historical Society)

- Father John Schoenmakers S. J.– Apostle to the Osages, W.W. Graves, 1928

- Getting Sense - The Osages and Their Missionaries, James D. White, 1997 (White takes a slightly different slant at telling the Osage history. It is an interesting book but expensive. However, it is available via inter-library loan from several area libraries.)

- The Osages – Children of the Middle Waters, John Joseph Mathews, 1961

- I adapted the header art from an image that appears in many web pages for gamers, game developers, sports enthusiasts and relationship counselors (interesting). The closest to a credit I could find was a video game site which tagged it “Comicus67”. If I have violated anyone’s copyright please let me know.