People's Party candidate nominating convention held at Columbus, Nebraska, July 15, 1890 (Wikipedia photo)

Mary Elizabeth Lease - Queen of the Populists.

A definition of Firebrand: “a person who is passionate about a particular cause, typically inciting change and taking radical action.” That fits Mary Elizabeth well and it was a trait she inherited from flaming Irish Patriot Joseph P. Clyens — her father.

Mary Elizabeth Lease - Queen of the Populists.

A definition of Firebrand: “a person who is passionate about a particular cause, typically inciting change and taking radical action.” That fits Mary Elizabeth well and it was a trait she inherited from flaming Irish Patriot Joseph P. Clyens — her father.

Mary Elizabeth Lease [2]

Mary Elizabeth Lease [2]

Struggle.

In his book “Queen of the Populists”[1] Richard Stiller describes the Clyens family story in a chapter called “Struggle.” During the days of the Irish potato famines, 1845-1847, the Clyens family were one step above the peasant class. Joseph Clyens was a squireen in County Monaghan in Northern Ireland. His wife, Elizabeth, was of Scottish descent. Squireen was an Irish term that meant “little squire”—a man who owns a small farm. Also, Elizabeth was a niece of the Bishop of Dublin and this raised the family status a little higher. In fact, they were able to hide a little cash at their home because they didn’t trust the banks or English government.

Joseph Clyens was an angry man. He believed the government could have helped the starving peasants; and he thought the government was profiting from the sale of grain that had been sent from America as aid. Clyens began to collect arms and comrades with the intent of launching a rebellion. When the government found out he was declared a traitor which was punishable by hanging. Joseph and Elizabeth decided to use their cash to flee to America. Their property was seized by the Crown.

The family settled in Ridgeway, Pennsylvania where Mary Elizabeth was born on September 11, 1853. The Clyens family discovered that farming in Pennsylvania was much different than Ireland. Also, without the link to aristocracy they had in Ireland, life here was difficult. In a short time they were desperately poor.

The Civil War started when Mary was eight. President Lincoln needed Union soldiers and the government began the first draft. However, in those days a prosperous man could buy a substitute for $300. Perhaps John Clyens carried over some of his patriotism from Ireland; or it might have been desperation that led John and two grown sons to sign up and give their $900 to Elizabeth and the children. Then, the three men took up arms and marched to their deaths. The two sons died of wounds at the battles of Fredericksburg and Lookout Mountain. Joseph Clyens was captured and imprisoned at the notorious Andersonville death camp. When Mary Elizabeth learned that her father was starved to death in captivity; she developed a life-long hatred of the Democrats who led the Confederate succession movement.

Elizabeth Clyens was able to achieve enough prosperity to educate her children. Mary Elizabeth attended St. Elizabeth’s Boarding Academy in Allegheny where she was a superior student. When she graduated at age fifteen, she had been exposed to the arts, literature and had studied several languages. She also wrote poems that were published locally. After graduation she began to teach at Ceres, New York which was just across the state line from Ridgeway. She enjoyed teaching but teachers were in strong supply and wages were low. She also noted that wages for women teachers were much less than men. That didn’t set well with Mary.

In his book “Queen of the Populists”[1] Richard Stiller describes the Clyens family story in a chapter called “Struggle.” During the days of the Irish potato famines, 1845-1847, the Clyens family were one step above the peasant class. Joseph Clyens was a squireen in County Monaghan in Northern Ireland. His wife, Elizabeth, was of Scottish descent. Squireen was an Irish term that meant “little squire”—a man who owns a small farm. Also, Elizabeth was a niece of the Bishop of Dublin and this raised the family status a little higher. In fact, they were able to hide a little cash at their home because they didn’t trust the banks or English government.

Joseph Clyens was an angry man. He believed the government could have helped the starving peasants; and he thought the government was profiting from the sale of grain that had been sent from America as aid. Clyens began to collect arms and comrades with the intent of launching a rebellion. When the government found out he was declared a traitor which was punishable by hanging. Joseph and Elizabeth decided to use their cash to flee to America. Their property was seized by the Crown.

The family settled in Ridgeway, Pennsylvania where Mary Elizabeth was born on September 11, 1853. The Clyens family discovered that farming in Pennsylvania was much different than Ireland. Also, without the link to aristocracy they had in Ireland, life here was difficult. In a short time they were desperately poor.

The Civil War started when Mary was eight. President Lincoln needed Union soldiers and the government began the first draft. However, in those days a prosperous man could buy a substitute for $300. Perhaps John Clyens carried over some of his patriotism from Ireland; or it might have been desperation that led John and two grown sons to sign up and give their $900 to Elizabeth and the children. Then, the three men took up arms and marched to their deaths. The two sons died of wounds at the battles of Fredericksburg and Lookout Mountain. Joseph Clyens was captured and imprisoned at the notorious Andersonville death camp. When Mary Elizabeth learned that her father was starved to death in captivity; she developed a life-long hatred of the Democrats who led the Confederate succession movement.

Elizabeth Clyens was able to achieve enough prosperity to educate her children. Mary Elizabeth attended St. Elizabeth’s Boarding Academy in Allegheny where she was a superior student. When she graduated at age fifteen, she had been exposed to the arts, literature and had studied several languages. She also wrote poems that were published locally. After graduation she began to teach at Ceres, New York which was just across the state line from Ridgeway. She enjoyed teaching but teachers were in strong supply and wages were low. She also noted that wages for women teachers were much less than men. That didn’t set well with Mary.

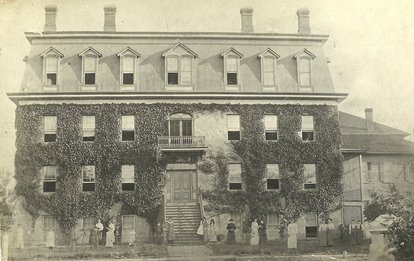

St. Ann's Academy Main Building, Osage Mission Kansas

St. Ann's Academy Main Building, Osage Mission Kansas

Osage Mission, Kansas.

She heard about Kansas. It was a new state that had joined the union in 1861. It was a state that had fought slavery even before the war. There was good government land that was being made available to the people. New towns seemed to be popping up daily. Women in Kansas had more freedom to speak their minds. Kansas needed people. Most importantly, Kansas needed teachers who would be well paid. In 1870 Mary Elizabeth Clyens sent an application to St. Ann’s Academy girl’s school in the new town of Osage Mission. Fr. John Schoenmakers, was impressed with her honors certificate from a good Catholic academy and she was hired.

When she arrived she found the town of Osage Mission to be fascinating but much different than the Pennsylvania-New York countryside. The landscape was flat but nearly everything around the sprawling settlement was new including the inhabitants. When she arrived in 1870 most of the Osage Indians had left, the town had just been started and new buildings were going up everywhere. There was promise that a large, stone church would be built across the road from the St. Ann’s campus. It was exciting and she loved the school, students and staff.

At age seventeen Mary Elizabeth was exhibiting a strong-minded boldness that was not appreciated in women of that day. St. Ann’s superior, Mother Bridget Hayden, expressed concern that some of her behavior and beliefs might be signs of a weakening Catholic faith. But Mary was an excellent teacher who, otherwise, fit in well. Mother Bridget’s instinct was probably accurate because Mary took up with a local non-Catholic druggist and in January of 1873, Mary and Charles Lease were married.

It was not a marriage made in heaven, but it did weather some early difficulties. Charles did not have strong political convictions, and she was able to overlook the fact that the shy, industrious man was a Democrat. Both wanted to try their hands at farming and the Homestead Act made land available to settlers willing to commit to a five-year stay on a land claim.

When the Leases staked their 160 acre claim near present Kingman, Kansas, they probably had no idea of what they were getting themselves into!

She heard about Kansas. It was a new state that had joined the union in 1861. It was a state that had fought slavery even before the war. There was good government land that was being made available to the people. New towns seemed to be popping up daily. Women in Kansas had more freedom to speak their minds. Kansas needed people. Most importantly, Kansas needed teachers who would be well paid. In 1870 Mary Elizabeth Clyens sent an application to St. Ann’s Academy girl’s school in the new town of Osage Mission. Fr. John Schoenmakers, was impressed with her honors certificate from a good Catholic academy and she was hired.

When she arrived she found the town of Osage Mission to be fascinating but much different than the Pennsylvania-New York countryside. The landscape was flat but nearly everything around the sprawling settlement was new including the inhabitants. When she arrived in 1870 most of the Osage Indians had left, the town had just been started and new buildings were going up everywhere. There was promise that a large, stone church would be built across the road from the St. Ann’s campus. It was exciting and she loved the school, students and staff.

At age seventeen Mary Elizabeth was exhibiting a strong-minded boldness that was not appreciated in women of that day. St. Ann’s superior, Mother Bridget Hayden, expressed concern that some of her behavior and beliefs might be signs of a weakening Catholic faith. But Mary was an excellent teacher who, otherwise, fit in well. Mother Bridget’s instinct was probably accurate because Mary took up with a local non-Catholic druggist and in January of 1873, Mary and Charles Lease were married.

It was not a marriage made in heaven, but it did weather some early difficulties. Charles did not have strong political convictions, and she was able to overlook the fact that the shy, industrious man was a Democrat. Both wanted to try their hands at farming and the Homestead Act made land available to settlers willing to commit to a five-year stay on a land claim.

When the Leases staked their 160 acre claim near present Kingman, Kansas, they probably had no idea of what they were getting themselves into!

Prairie Dugout Home (Santa Fe Trail Center, Larned, KS)

Prairie Dugout Home (Santa Fe Trail Center, Larned, KS)

Failures.

Prairie life was brutal. Their first shelter was a tent; then a dugout with a canvas top. Finally Charles was able to construct a sod home with dirt floors that crumbled during dry weather; and the sod walls were either dusty or muddy. The work was exhausting, weather was dry and in spite of their effort, the returns were minimal. The farmer was on the bottom of the feeding chain. Dealers, railroads and eastern businesses enjoyed most of the benefits of their labor. Worst of all, the prairie homesteads were lonely. Bone-numbing isolation drove weaker settlers to drink or madness. Some simply died of exposure or suicide.

Failure and exhaustion led the Leases to Denison, Texas in the late summer of 1874. There Charles could practice his profession of pharmacy. While not prosperous, they did enjoy a modest home with wood floors and glass windows. It was also in Denison that the first of four children, Charles Henry, was born. Denison was a wild railroad and cattle town but it also had a respectable side. Mary was able to associate with women with similar interests and became a leader of a women’s activist group that was promoting, among other things, suffrage and prohibition. Charles Lease and the other husbands were not thrilled.

In the winter of 1883 two things occurred: A daughter was born and they made a decision to try farming again. They moved back to Kingman and enjoyed a little more success. Good weather replaced grasshoppers and drought. They produced a good corn crop. While corn sold at good prices in the eastern cities, nothing was left for the farmers after others took the profits. With no money left for seed, repairs or livestock, the Leases failed again. By the time the Leases moved to Wichita in 1884 life had taught Mary Elizabeth three things:

Prairie life was brutal. Their first shelter was a tent; then a dugout with a canvas top. Finally Charles was able to construct a sod home with dirt floors that crumbled during dry weather; and the sod walls were either dusty or muddy. The work was exhausting, weather was dry and in spite of their effort, the returns were minimal. The farmer was on the bottom of the feeding chain. Dealers, railroads and eastern businesses enjoyed most of the benefits of their labor. Worst of all, the prairie homesteads were lonely. Bone-numbing isolation drove weaker settlers to drink or madness. Some simply died of exposure or suicide.

Failure and exhaustion led the Leases to Denison, Texas in the late summer of 1874. There Charles could practice his profession of pharmacy. While not prosperous, they did enjoy a modest home with wood floors and glass windows. It was also in Denison that the first of four children, Charles Henry, was born. Denison was a wild railroad and cattle town but it also had a respectable side. Mary was able to associate with women with similar interests and became a leader of a women’s activist group that was promoting, among other things, suffrage and prohibition. Charles Lease and the other husbands were not thrilled.

In the winter of 1883 two things occurred: A daughter was born and they made a decision to try farming again. They moved back to Kingman and enjoyed a little more success. Good weather replaced grasshoppers and drought. They produced a good corn crop. While corn sold at good prices in the eastern cities, nothing was left for the farmers after others took the profits. With no money left for seed, repairs or livestock, the Leases failed again. By the time the Leases moved to Wichita in 1884 life had taught Mary Elizabeth three things:

- She had an ability to lead and was a good speaker. The women’s group in Denison always let her take front stage at events and she received praise for her speaking.

- She hated the railroads, eastern banks and big businessmen as much as the Democrats. The farmers, miners and other labor groups had no chance to succeed with Wall Street and a greed-motivated government.

- She had become tough and nearly fearless.

Wichita and Opportunity.

Life in Wichita was still difficult but it also provided opportunity. Charles found pharmacy work and she supplemented income by doing laundry for people. She had considered law as a profession and now she knew her gift for speaking and her quick mind would fit the profession well. At the time an apprentice could work with a law firm to “read law” without actually going to school. She found a way to read law for the Aldrich and Brown law firm while watching three children, doing other people's and her own family washing and keeping the home orderly. As she took individual exams, she passed them easily. While doing all of this, child number four was born and she passed her final bar exam. On the day she was admitted to the bar she made her first address to a jury and astonished a courtroom with the force of her presence.

Now she had access to the Wichita elite. She began to mingle with wives of local businessmen, attorneys and politicians and started another women’s activist group—and local leaders began to notice her. It was during this period that Charles became less tolerant of his wife’s activism. At one point, the invitation of a local male republican editor to their home led to a loud argument and a fist fight that brought the police but no charges. This, plus increasing demand for his wife’s speaking services was the beginning of the end.

Life in Wichita was still difficult but it also provided opportunity. Charles found pharmacy work and she supplemented income by doing laundry for people. She had considered law as a profession and now she knew her gift for speaking and her quick mind would fit the profession well. At the time an apprentice could work with a law firm to “read law” without actually going to school. She found a way to read law for the Aldrich and Brown law firm while watching three children, doing other people's and her own family washing and keeping the home orderly. As she took individual exams, she passed them easily. While doing all of this, child number four was born and she passed her final bar exam. On the day she was admitted to the bar she made her first address to a jury and astonished a courtroom with the force of her presence.

Now she had access to the Wichita elite. She began to mingle with wives of local businessmen, attorneys and politicians and started another women’s activist group—and local leaders began to notice her. It was during this period that Charles became less tolerant of his wife’s activism. At one point, the invitation of a local male republican editor to their home led to a loud argument and a fist fight that brought the police but no charges. This, plus increasing demand for his wife’s speaking services was the beginning of the end.

Mary Elizabeth Lease (Wichita Eagle and Lawrence Journal World)

Mary Elizabeth Lease (Wichita Eagle and Lawrence Journal World)

An Orator.

In the late 1880’s there was no television or radio. Moving pictures were crude and “movie theaters” would not appear until the 1900’s. Opinions, education and information were often shared by skilled, eloquent speakers. Skilled orators might be paid, and very skilled speakers were paid well. Mary Elizabeth Lease is still recognized as one of the most skilled and powerful political orators of the time—and she had a cause. By the late 1880’s the government and Wall Street attitudes toward labor and the common people were near a breaking point. The People’s Party, also known as the Populists, were championing the small men. Kansas and Nebraska were becoming hot spots. Being able to publicly express her disgust against Wall Street, big business and a greedy government was right down Mary Elizabeth Leases’ alley and the Populists wanted her.

Nearing the age of forty, Mary Elizabeth Lease was an attractive woman. She was well-dressed, often in black, slender and rather tall. Much of the time she wore her hair in a bun on top of her head, or she wore a hat that accentuated her height. She was an imposing figure before she started to speak. When she began a speech she became formidable—especially if she was speaking against you. She had a deep voice for a woman and was a master of inflection. She never spoke from notes—she always connected with the audience early and spoke from the heart. Even without amplification equipment she routinely incited large crowds to fever pitch. It was reported that at one rural venue a farmer stepped up to the stage, opened his jacket, gripped the pistol in his belt and said “What do you need us to do?”

One of her most famous quotes, often used in speeches in the rural areas, was: “You farmers need to raise less corn and more hell!” In those days the word “hell” coming from a woman’s mouth was considered to be uncouth. Later she admitted that it wasn’t her who coined the comment, but she considered it to be “right good advice.”

During much of the 1890’s she was on the road constantly, sometimes traveling from coast to coast. During these trips she often took one or more of the children with her. In later years her oldest son, Charles Henry, actually took charge of some of her event planning. She spoke at conventions in front of the largest crowds ever assembled; and sometimes gave as many as ten speeches a day. But by the mid-to-late 1890’s the Populist fusion with the Democrats dampened her enthusiasm with the party and eventually destroyed the Populist movement. By then her marriage to Charles was pretty well over.

In the late 1880’s there was no television or radio. Moving pictures were crude and “movie theaters” would not appear until the 1900’s. Opinions, education and information were often shared by skilled, eloquent speakers. Skilled orators might be paid, and very skilled speakers were paid well. Mary Elizabeth Lease is still recognized as one of the most skilled and powerful political orators of the time—and she had a cause. By the late 1880’s the government and Wall Street attitudes toward labor and the common people were near a breaking point. The People’s Party, also known as the Populists, were championing the small men. Kansas and Nebraska were becoming hot spots. Being able to publicly express her disgust against Wall Street, big business and a greedy government was right down Mary Elizabeth Leases’ alley and the Populists wanted her.

Nearing the age of forty, Mary Elizabeth Lease was an attractive woman. She was well-dressed, often in black, slender and rather tall. Much of the time she wore her hair in a bun on top of her head, or she wore a hat that accentuated her height. She was an imposing figure before she started to speak. When she began a speech she became formidable—especially if she was speaking against you. She had a deep voice for a woman and was a master of inflection. She never spoke from notes—she always connected with the audience early and spoke from the heart. Even without amplification equipment she routinely incited large crowds to fever pitch. It was reported that at one rural venue a farmer stepped up to the stage, opened his jacket, gripped the pistol in his belt and said “What do you need us to do?”

One of her most famous quotes, often used in speeches in the rural areas, was: “You farmers need to raise less corn and more hell!” In those days the word “hell” coming from a woman’s mouth was considered to be uncouth. Later she admitted that it wasn’t her who coined the comment, but she considered it to be “right good advice.”

During much of the 1890’s she was on the road constantly, sometimes traveling from coast to coast. During these trips she often took one or more of the children with her. In later years her oldest son, Charles Henry, actually took charge of some of her event planning. She spoke at conventions in front of the largest crowds ever assembled; and sometimes gave as many as ten speeches a day. But by the mid-to-late 1890’s the Populist fusion with the Democrats dampened her enthusiasm with the party and eventually destroyed the Populist movement. By then her marriage to Charles was pretty well over.

Later Life.

By 1900 there was nothing left for her in Wichita. She was one of the most famous women in the United States but was far from wealthy. She had dedicated much of her life to politics but, outside of a brief political appointment, she had never held office. She heard of lecturing and writing opportunities up northeast. Sometime after 1896 she moved to New York where she finally found some financial comfort. Public lecture was popular and she could ask $100 to $150 per appearance—a large sum in those days. Some of her talks were as far away as California, and others in Kansas. She could also be more flexible with her speaking topics. A favorite subject was Irish history and multitudes of Irish immigrants enjoyed her lively descriptions of Irish life injected with some well-imitated brogue.

While writing was not one of her stronger suites her opinions were valued by publishers. She was hired to report for Joseph Pulitzer and his New York World. She also wrote for The National Encyclopedia of American Biography and the New York Press Bureau.

As her income grew she was able to do more with her children; all of whom eventually, located to New York. Son Charlie continued to manage much of her business until he died suddenly of a ruptured appendix. In later years she was able to buy a small farm in the Delaware Valley, near Callicoon, New York. She was a farmer’s daughter, a farmer’s wife and the farmer’s champion. Now she could settle on her own place with little fear of failure.

Back at Osage Mission - St. Paul the locals kept track of her with occasional newspaper articles. The May 29, 1902, issue of the St. Paul Journal noted that Mary E. Lease traveled back to Kansas and was granted a divorce from Charles E. Lease on May 22. In November of 1933 the Journal reported that she passed away on October 29. It was also mentioned that nearly all of the demands that she and the Populists made during the 1890’s had come to truth—it just took a little more time than she had expected.

But she was not a patient woman.

By 1900 there was nothing left for her in Wichita. She was one of the most famous women in the United States but was far from wealthy. She had dedicated much of her life to politics but, outside of a brief political appointment, she had never held office. She heard of lecturing and writing opportunities up northeast. Sometime after 1896 she moved to New York where she finally found some financial comfort. Public lecture was popular and she could ask $100 to $150 per appearance—a large sum in those days. Some of her talks were as far away as California, and others in Kansas. She could also be more flexible with her speaking topics. A favorite subject was Irish history and multitudes of Irish immigrants enjoyed her lively descriptions of Irish life injected with some well-imitated brogue.

While writing was not one of her stronger suites her opinions were valued by publishers. She was hired to report for Joseph Pulitzer and his New York World. She also wrote for The National Encyclopedia of American Biography and the New York Press Bureau.

As her income grew she was able to do more with her children; all of whom eventually, located to New York. Son Charlie continued to manage much of her business until he died suddenly of a ruptured appendix. In later years she was able to buy a small farm in the Delaware Valley, near Callicoon, New York. She was a farmer’s daughter, a farmer’s wife and the farmer’s champion. Now she could settle on her own place with little fear of failure.

Back at Osage Mission - St. Paul the locals kept track of her with occasional newspaper articles. The May 29, 1902, issue of the St. Paul Journal noted that Mary E. Lease traveled back to Kansas and was granted a divorce from Charles E. Lease on May 22. In November of 1933 the Journal reported that she passed away on October 29. It was also mentioned that nearly all of the demands that she and the Populists made during the 1890’s had come to truth—it just took a little more time than she had expected.

But she was not a patient woman.

Some Reference Information:

[1] I drew much of the above from “Queen of the Populists, The Story of Mary Elizabeth Lease” Richard Stiller, Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York, Copyright 1970. At the time it was part of an eight book series about Women of America. For those interested some of my other reference sources are below:

The above W. W. Graves sources also provide more details and snippets about Elizabeth and Charles’ life at Osage Mission before their departure.

Beacon on the Plains, by Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald (Copyright 1939) discusses Mother Bridget Hayden’s concern about Elizabeth’s pending marriage to non-Catholic Charles Lease.

In addition to the above, there are many web sources for information about Mary Elizabeth Lease and the late 19th century Populist movement. I listed only a couple of them above. Not all agree on details but I used Richard Stiller's book as a tie-breaker where possible.

[2] The photo of Mary Elizabeth Lease was downloaded from Wikipedia—one of dozens of sources for the picture.

[1] I drew much of the above from “Queen of the Populists, The Story of Mary Elizabeth Lease” Richard Stiller, Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York, Copyright 1970. At the time it was part of an eight book series about Women of America. For those interested some of my other reference sources are below:

- Annals of Osage Mission by W. W. Graves notes her birth-date and marriage to Charles Clyens.

- The Kansaspedia webpage by the Kansas Historical Society includes a biography that clarifies her birth date as compared to other sources. It also quotes William Allen White in saying "she could recite the multiplication table and set a crowd hooting and harrahing at her will." He respected her but was not one of her followers. https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/mary-elizabeth-lease/12128

- The Plains Humanities website provides a good, brief bio at: http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.pd.032

- W.W. Graves History of Neosho County, Volume 2 provides a two-page synopsis of her life under the heading “Remarkable Women.”

The above W. W. Graves sources also provide more details and snippets about Elizabeth and Charles’ life at Osage Mission before their departure.

Beacon on the Plains, by Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald (Copyright 1939) discusses Mother Bridget Hayden’s concern about Elizabeth’s pending marriage to non-Catholic Charles Lease.

In addition to the above, there are many web sources for information about Mary Elizabeth Lease and the late 19th century Populist movement. I listed only a couple of them above. Not all agree on details but I used Richard Stiller's book as a tie-breaker where possible.

[2] The photo of Mary Elizabeth Lease was downloaded from Wikipedia—one of dozens of sources for the picture.