17 Sisters

The September 1930, reinterment Mass for the pioneer Sisters of Loretto, at St.Paul, was likely the most remarkable such service in Kansas history — but no more remarkable than the lives those women lived.

The September 1930, reinterment Mass for the pioneer Sisters of Loretto, at St.Paul, was likely the most remarkable such service in Kansas history — but no more remarkable than the lives those women lived.

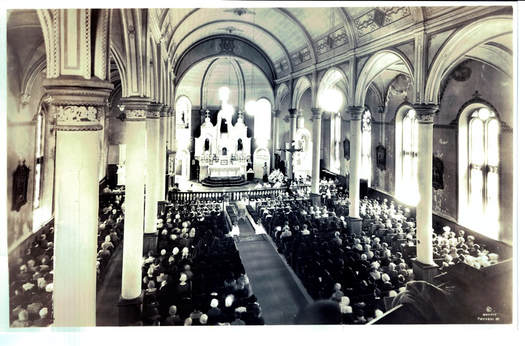

St. Francis Catholic Church, September 15, 1930 (Click to enlarge).

St. Francis Catholic Church, September 15, 1930 (Click to enlarge).

The Photo.

The photo shown here is nearly forgotten but it records one of the most significant moments in St. Paul’s past (click to enlarge). The yellowed black and white photograph was taken from the choir loft of St. Francis Catholic Church.

Some things pop out at first sight. The glare of the old chandeliers and east windows seem like unintentional highlights rendered by the early film. Also, the church showed signs that the fresco wall treatment of thirty years earlier was in need of repair. The church was packed. Pews were full and people appear to be seated in chairs in front of the pews. Forward of the Communion Rail, there were thirty or more clergy and servers sitting in chairs or standing. Coats thrown over the choir loft rail in the foreground suggest the loft was full too. There were the habits of many, many nuns.

But the scene at center-aisle and behind the Communion Rail is extraordinary (top banner). A coffin surrounded by sixteen black boxes. The coffin and boxes contained the remains of the women who served the Catholic Osage Mission and the town of Osage Mission [1] between 1847 and 1894 — seventeen coffins.

The photo shown here is nearly forgotten but it records one of the most significant moments in St. Paul’s past (click to enlarge). The yellowed black and white photograph was taken from the choir loft of St. Francis Catholic Church.

Some things pop out at first sight. The glare of the old chandeliers and east windows seem like unintentional highlights rendered by the early film. Also, the church showed signs that the fresco wall treatment of thirty years earlier was in need of repair. The church was packed. Pews were full and people appear to be seated in chairs in front of the pews. Forward of the Communion Rail, there were thirty or more clergy and servers sitting in chairs or standing. Coats thrown over the choir loft rail in the foreground suggest the loft was full too. There were the habits of many, many nuns.

But the scene at center-aisle and behind the Communion Rail is extraordinary (top banner). A coffin surrounded by sixteen black boxes. The coffin and boxes contained the remains of the women who served the Catholic Osage Mission and the town of Osage Mission [1] between 1847 and 1894 — seventeen coffins.

A Plan to Move the Loretto’s.

The photo was taken in September of 1930. Three of the pioneer women in the coffins had arrived on October 10, 1847, and started the Osage girl’s school on the date of their arrival. The other fourteen came later and served in various capacities such as educators, administrators, or support staff. Many had seen southeast Kansas grow from desolate, unsettled grassland into a landscape of thriving settlements and farms. Some of the women endured the Civil War and had fed or dressed wounds for both Union and Confederate soldiers. They were the silent backbone of the Catholic Mission that kept it going during difficulty and successes. During the early 1870’s they transitioned the Osage Manual Labor Schools into public schools and one of the most respected frontier women’s schools — St. Ann’s Academy. The Osage Mission Loretto’s were refined, well-educated women but their time on the prairie had toughened them.

Prior to the destruction of St. Ann’s Academy the Loretto’s maintained a small, well-kept cemetery east of the academy buildings [2]. After the departure of the Loretto’s in 1896, the Loretto land and Academy ruins were turned over to a caretaker who lived on the grounds and began a garden. Over the years the garden expanded, and the land east of the ruins was under cultivation except for the small cemetery plot. Eventually, it was only accessible through plowed fields.

When the cemetery started showing signs of neglect, the Passionist Fathers, across the street, requested permission from the Loretto’s in Nerinx, Kentucky, to move the seventeen graves ¼ mile east to St. Francis Cemetery. Permission was granted and Reverend Theodore Judd, C. P., rector of the Passionist Monastery in St. Paul, set his reinterment plan in motion.

The photo was taken in September of 1930. Three of the pioneer women in the coffins had arrived on October 10, 1847, and started the Osage girl’s school on the date of their arrival. The other fourteen came later and served in various capacities such as educators, administrators, or support staff. Many had seen southeast Kansas grow from desolate, unsettled grassland into a landscape of thriving settlements and farms. Some of the women endured the Civil War and had fed or dressed wounds for both Union and Confederate soldiers. They were the silent backbone of the Catholic Mission that kept it going during difficulty and successes. During the early 1870’s they transitioned the Osage Manual Labor Schools into public schools and one of the most respected frontier women’s schools — St. Ann’s Academy. The Osage Mission Loretto’s were refined, well-educated women but their time on the prairie had toughened them.

Prior to the destruction of St. Ann’s Academy the Loretto’s maintained a small, well-kept cemetery east of the academy buildings [2]. After the departure of the Loretto’s in 1896, the Loretto land and Academy ruins were turned over to a caretaker who lived on the grounds and began a garden. Over the years the garden expanded, and the land east of the ruins was under cultivation except for the small cemetery plot. Eventually, it was only accessible through plowed fields.

When the cemetery started showing signs of neglect, the Passionist Fathers, across the street, requested permission from the Loretto’s in Nerinx, Kentucky, to move the seventeen graves ¼ mile east to St. Francis Cemetery. Permission was granted and Reverend Theodore Judd, C. P., rector of the Passionist Monastery in St. Paul, set his reinterment plan in motion.

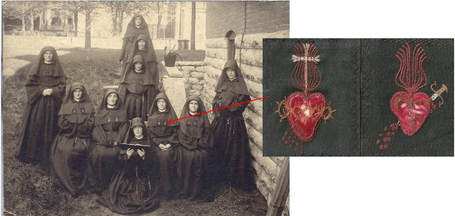

Sisters of Loretto and Sacred Heart Images (click to enlarge)

Sisters of Loretto and Sacred Heart Images (click to enlarge)

Men of the parish began the meticulous process of digging up each grave. The remains were identified by grave location and were placed in separate containers. The first sister had been buried in 1867 and the last in 1894. Little remained in the graves except for bones, scraps of habits, and the Sacred Heart images embroidered on the front of the Loretto habits. The original caskets had long-ago disintegrated.

There was one exception. Mother Bridget Hayden had been in the earth for forty years and the lower part of her casket remained. Her body and habit were in a remarkable state of preservation.

The exhumed bodies were taken to the basement chapel of St. Francis Catholic Church where the caskets were finally prepared. Sixteen child-sized containers and one full-sized casket for Mother Bridget. During the exhumation, word of the condition of Mother Bridget’s remains spread like wildfire. The remains lied in repose for some time and scientists, scholars, and newsmen were puzzled about the incorrupt condition of Mother Bridget’s body. Older local residents — the Osage Mission settlers — were not puzzled in the least:

“See. We told you Mother Bridget was a saint. There's your proof!”

There was one exception. Mother Bridget Hayden had been in the earth for forty years and the lower part of her casket remained. Her body and habit were in a remarkable state of preservation.

The exhumed bodies were taken to the basement chapel of St. Francis Catholic Church where the caskets were finally prepared. Sixteen child-sized containers and one full-sized casket for Mother Bridget. During the exhumation, word of the condition of Mother Bridget’s remains spread like wildfire. The remains lied in repose for some time and scientists, scholars, and newsmen were puzzled about the incorrupt condition of Mother Bridget’s body. Older local residents — the Osage Mission settlers — were not puzzled in the least:

“See. We told you Mother Bridget was a saint. There's your proof!”

A Mass of Celebration, Not Mourning.

Five of the Loretto’s were originally buried from the original log mission church. One had already been moved from an old mission cemetery to the small Loretto Cemetery. Now a single Mass would be celebrated, for all seventeen sisters, and they would be taken to a prominent resting place. That place was in the center of St. Francis Catholic Cemetery. Founding women of Kansas would now rest across a cemetery path from their Jesuit counterparts who started many missions and churches in our state.

The service itself was held on September 15, 1930, in the majestic stone church that replaced the log mission church forty-six year earlier. Priests, Sisters and laity representing almost every parish in the diocese were in attendance; along with members of statewide press groups and local citizens. With extra seating St. Francis can accommodate nearly 1,000 people and that was not enough. Some estimates said at least two hundred people waited outside of the entrance for the funeral procession. The cemetery burial was witnessed by about two thousand.

Before the services, ten Sisters of Loretto quietly entered the church down the main aisle on a path of flower petals strewn by flower girls. Some of the women had worked with the deceased. Immediately after the Loretto’s, a Fourth Degree Knights of Columbus Honor Guard entered by the side aisles and took seats near the front of the church.

The Solomon Requiem Mass was read by Very Rev. Eugene Creegan C. P., Provincial of the Passionist Fathers of Chicago with Rev J. M. Monnier, of Humboldt, Kansas, as Deacon and Rev. A. P. Heimann of Piqua, Kansas, as Sub-deacon. The Very Rev. Theodore Judd, C. P., Rector of the St, Paul Passionist Monastery served as Master of Ceremonies and Rev. John Fox, C. P. delivered an eloquent sermon that was beautiful in text and delivered with the inspiration of the moment. Father Fox’s message was not a funeral message — it was not a funeral. The time for mourning the seventeen women was long past. It was time to celebrate the remarkable lives these women had lived. [7]

Five of the Loretto’s were originally buried from the original log mission church. One had already been moved from an old mission cemetery to the small Loretto Cemetery. Now a single Mass would be celebrated, for all seventeen sisters, and they would be taken to a prominent resting place. That place was in the center of St. Francis Catholic Cemetery. Founding women of Kansas would now rest across a cemetery path from their Jesuit counterparts who started many missions and churches in our state.

The service itself was held on September 15, 1930, in the majestic stone church that replaced the log mission church forty-six year earlier. Priests, Sisters and laity representing almost every parish in the diocese were in attendance; along with members of statewide press groups and local citizens. With extra seating St. Francis can accommodate nearly 1,000 people and that was not enough. Some estimates said at least two hundred people waited outside of the entrance for the funeral procession. The cemetery burial was witnessed by about two thousand.

Before the services, ten Sisters of Loretto quietly entered the church down the main aisle on a path of flower petals strewn by flower girls. Some of the women had worked with the deceased. Immediately after the Loretto’s, a Fourth Degree Knights of Columbus Honor Guard entered by the side aisles and took seats near the front of the church.

The Solomon Requiem Mass was read by Very Rev. Eugene Creegan C. P., Provincial of the Passionist Fathers of Chicago with Rev J. M. Monnier, of Humboldt, Kansas, as Deacon and Rev. A. P. Heimann of Piqua, Kansas, as Sub-deacon. The Very Rev. Theodore Judd, C. P., Rector of the St, Paul Passionist Monastery served as Master of Ceremonies and Rev. John Fox, C. P. delivered an eloquent sermon that was beautiful in text and delivered with the inspiration of the moment. Father Fox’s message was not a funeral message — it was not a funeral. The time for mourning the seventeen women was long past. It was time to celebrate the remarkable lives these women had lived. [7]

The Loretto Plot (Click to Enlarge)

The Loretto Plot (Click to Enlarge)

A Burial Procession Like None Other.

After the ceremony, the tower bells began a slow tolling as the procession to the cemetery began. Sixteen small coffins were borne on the shoulders of sons of former students of St. Ann’s Academy. A team of six pallbearers carried the full-sized coffin of Mother Bridget Hayden. As the church bells tolled, the procession extended from the church steps to the burial spot in St. Francis Cemetery.

Today, Mother Bridget’s gravestone is found under a small, round cedar tree and the stones of her sisters surround her [3].

After the ceremony, the tower bells began a slow tolling as the procession to the cemetery began. Sixteen small coffins were borne on the shoulders of sons of former students of St. Ann’s Academy. A team of six pallbearers carried the full-sized coffin of Mother Bridget Hayden. As the church bells tolled, the procession extended from the church steps to the burial spot in St. Francis Cemetery.

Today, Mother Bridget’s gravestone is found under a small, round cedar tree and the stones of her sisters surround her [3].

|

Sisters of Loretto Buried in St. Francis Cemetery:

Sister Mary Regis Lawrence - d. April 18, 1867.** Sister Mary Benvin Tracy - d. January 22, 1873. Sister Mary Vincentia McCool - d. July 10, 1873.* Sister Mary, Syra Bourdanais - d. December 27,1876. Sister Mary Borgia Martin - d. January 14, 1880. Sister Mary Bathildes Neighbors - d. November 30, 1884. Sister Mary Petronilla Fouche Van Prather - d. August 11, 1887.* Sister Philomena Bernier - d. March 10, 1887. Sister (Mother) Mary Bridget Hayden - d. January 23, 1890.* Sister Mary Teresa August McDonough - d. February 4, 1890. Sister Mary Eudocia White - d. February 19, 1890. Sister Mary Eugenia Friel - d. June 3, 1890. Sister Mary Teresa Bellier - d. October 11, 1890. Sister Mary Leo Cambern - d. July 28, 1891. Sister Mary Aloysius Connelly - d. July 31, 1893. Sister Mary Edwina Beddiger - d. August 8, 1892. Sister Mary Benedicta Kemna - d. October 7, 1894. Sister Alonza Smith - d. May 11,1983*** |

Vertical Divider

|

* Sisters Mary Bridget Hayden, Mary Vincentia McCool and Mary Petronella Fouche Van Prater were among the first group of Loretto missionaries who arrived in October of 1847 ** Sister Mary Regis Lawrence was originally buried in a small, mission cemetery that was located near the existing football field in St. Paul. The date of her removal to the Loretto Cemetery is unknown, but her grave site is recorded in Father Hugh Barr's notes [2]. *** Sister Alonza Smith was the daughter of Joe and Anna, O'Brien, Smith. She was a Sister of Loretto who was buried here after her death in El Paso, Texas, in 1983. |

Some Reference Information:

[1] The term “Osage Mission” includes the government Osage Indian school (Catholic Osage Mission) operated by the Jesuits, with the Loretto’s, from 1847 to 1870; and the town of Osage Mission that was founded in 1867 as the Catholic Mission operations wound down. The town of Osage Mission was renamed as St. Paul in 1895.

[1] The term “Osage Mission” includes the government Osage Indian school (Catholic Osage Mission) operated by the Jesuits, with the Loretto’s, from 1847 to 1870; and the town of Osage Mission that was founded in 1867 as the Catholic Mission operations wound down. The town of Osage Mission was renamed as St. Paul in 1895.

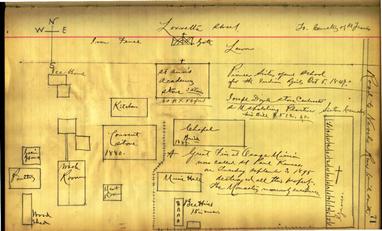

Figure 2-1. Click Father Barr's Map to Enlarge.

Figure 2-1. Click Father Barr's Map to Enlarge.

[2] An Educated Guess:

The location of the Loretto cemetery might be lost without the work of Passionist Father Hugh Barr. Father Barr was a Passionist historian who was given the assignment of writing the history of his order during the last decade of the 19th century. This brought him to Osage Mission on September 8 of 1894 at about the time the Passionist Monastery (former Jesuit Monastery) was activated. Father Barr remained at the mission until October 22 and compiled a body of handwritten information, sketches, and printed articles nearly all of which is written on or glued to yellowed ruled tablet paper. Among his sketches was a hand-drawn map of the St. Ann’s complex (Figure 2-1). His sketch shows the Loretto cemetery east of the school near the county road ("Road to Neosho River ...").

The location of the Loretto cemetery might be lost without the work of Passionist Father Hugh Barr. Father Barr was a Passionist historian who was given the assignment of writing the history of his order during the last decade of the 19th century. This brought him to Osage Mission on September 8 of 1894 at about the time the Passionist Monastery (former Jesuit Monastery) was activated. Father Barr remained at the mission until October 22 and compiled a body of handwritten information, sketches, and printed articles nearly all of which is written on or glued to yellowed ruled tablet paper. Among his sketches was a hand-drawn map of the St. Ann’s complex (Figure 2-1). His sketch shows the Loretto cemetery east of the school near the county road ("Road to Neosho River ...").

Figure 2-2. While not to scale, the overlay, compared with Father Barr's sketch, suggests the Loretto Cemetery was near the Museum schoolhouse and harness shop.

Figure 2-2. While not to scale, the overlay, compared with Father Barr's sketch, suggests the Loretto Cemetery was near the Museum schoolhouse and harness shop.

Comparing Father Barr's un-scaled sketch with an overlay of an 1882 Sanborn map, onto a satellite image of the existing Osage Mission - Neosho County Museum grounds, we can make an educated guess of the approximate location of the cemetery (Figure 3-2).

[3] Some photos of, and a satellite map of the existing St. Francis Cemetery, are shown HERE.

[4] Photos:

- The church photo, including the cropped banner, were scanned from a copy on file with the Osage Mission – Neosho County Historical Society.

- The photo of the group of Sisters of Loretto at Osage Mission – The Loretto Archives, Nerinx, Kentucky.

- Father Hugh Barr’s notebook image is one of more than 100 images from his 1894 visit to Osage Mission. We obtained a CD with both JPG images and a browser-enabled set of the images from the Passionist archive at Weinberg Memorial Library, The University of Scranton, PA.

- The satellite image overlay was made by combining a Google Earth Image of the museum grounds with an crop from an1892 Sanborn Map of St. Ann’s Academy. The Sanborn Map was obtained from the Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas by members of the Osage Mission – Neosho County Historical Society. At the time of writing the map was on display in the museum.

- The Life and Times of Mother Bridget, by W. W. Graves, Journal Press, St. Paul, Kansas, Copyrighted 1938.

- A large article titled "An Imposing Ceremony" in the September 18, 1930 issue of the St. Paul Journal.

- Beacon on the Plains by Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald, S.C.L., PhD, Copyright 1939, St, Mary College. The book includes a brief description of Mother Hayden's time here and the exhumation of the Lorettos. It is an excellent reference source for people wanting to acquaint themselves with the Catholic Mission. At the time of writing it is available from the Osage Mission - Neosho County Historical Society in St. Paul, Kansas.

- For more information about Mother Bridget Hayden, follow THIS LINK.

- For more information about St. Ann't Academy, follow THIS LINK.

- For more information about the Jesuit missionary work from Osage Mission, follow THIS LINK.