7. The Missionary Trails From Osage Mission

“Osage Mission was a great distributing center of civilization in the state because of the nature of its organization, the genius of the missionaries, the accessibility of its location, its long duration, and its numerous outposts flung across southern Kansas.”

Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald, Beacon on the Plains.

“Osage Mission was a great distributing center of civilization in the state because of the nature of its organization, the genius of the missionaries, the accessibility of its location, its long duration, and its numerous outposts flung across southern Kansas.”

Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald, Beacon on the Plains.

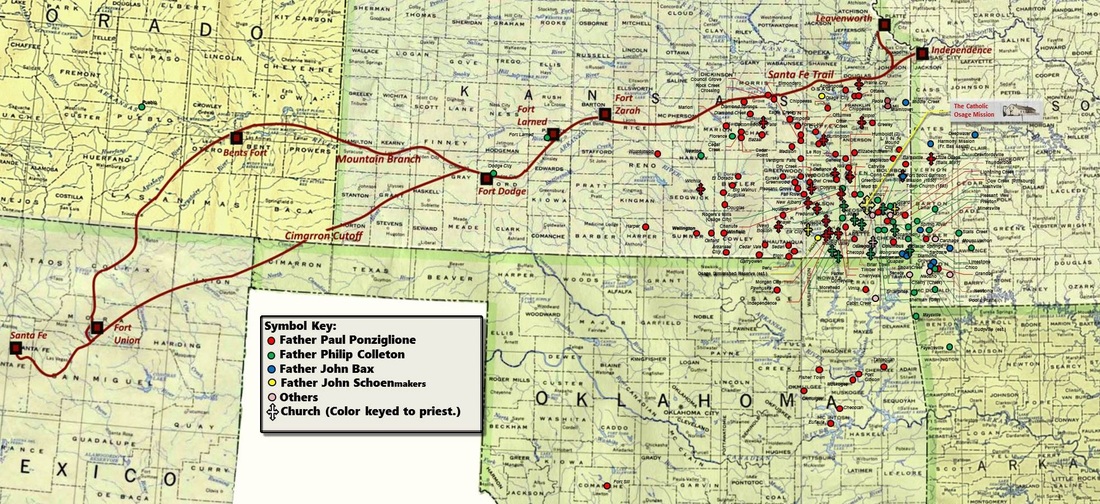

When Sister Fitzgerald wrote Beacon on the Plains in 1939, her focus was on Kansas. Appendix H of the book lists 113 missionary stations and churches established in Kansas by the Jesuits from Osage Mission. That number included Osage Mission itself.

Now we know that number exceeds 150 and we continue to find more. We also know that the Jesuit missionary range extended from Mount Vernon, Missouri, west to Pueblo Colorado; and from the Santa Fe Trail, south to central and southern Oklahoma. The number does not include three Wyoming missions served by Father Ponziglione after he left our Mission.

This is only one example of the widespread influence that emanated from our small southeast Kansas town.

The “Missions” of the Catholic Mission

The Catholic Mission was a government sponsored Indian school operated by the Jesuits. In that capacity it operated from 1847, winding down by 1870. What is less understood is another role of the Jesuit missionaries: That was disseminating the Catholic faith in the area south of the Santa Fe Trail. The term of this work spanned from 1847 well into the 1880’s and the Jesuits were very successful in this endeavor.

Now we know that number exceeds 150 and we continue to find more. We also know that the Jesuit missionary range extended from Mount Vernon, Missouri, west to Pueblo Colorado; and from the Santa Fe Trail, south to central and southern Oklahoma. The number does not include three Wyoming missions served by Father Ponziglione after he left our Mission.

This is only one example of the widespread influence that emanated from our small southeast Kansas town.

The “Missions” of the Catholic Mission

The Catholic Mission was a government sponsored Indian school operated by the Jesuits. In that capacity it operated from 1847, winding down by 1870. What is less understood is another role of the Jesuit missionaries: That was disseminating the Catholic faith in the area south of the Santa Fe Trail. The term of this work spanned from 1847 well into the 1880’s and the Jesuits were very successful in this endeavor.

The map above is unreadable but a mouse click enlarges it a bit. As you look at the image it is interesting to look for individual towns and locations. Perhaps it is more interesting to note the density of the dots as you move away from the Catholic Mission. The heaviest density of missionary work was in an area from Mt. Vernon, Missouri, west to Wichita, Kansas; and from the Santa Fe Trail, south to northern Oklahoma—but there are also many in east central Kansas to the western Oklahoma region. Then, you move west to the scattered outposts like Fort Larned, Dodge and Pueblo, Colorado. Many, not all, of the mission stations in the 100 mile radius were founded in the span of 1847 through the late 1860’s. The majority of those stations, and the Oklahoma stations, were founded and served by priests on horseback or horse and wagon.

Those who have hiked in mountains or canyons have found themselves surrounded by terrain, with no visual bearing beyond the immediate hills or rocks. If you have done so, you can appreciate the challenges of navigating the steep valleys of the Kansas Flint Hills or Oklahoma Osage hills using only time, sun position and a well-developed sense of direction. There were no water towers, power lines, hedge rows and only a few trails and dusty roads to assist with navigation. A few thoughts about the missionary trails of the Jesuits are discussed below:

Those who have hiked in mountains or canyons have found themselves surrounded by terrain, with no visual bearing beyond the immediate hills or rocks. If you have done so, you can appreciate the challenges of navigating the steep valleys of the Kansas Flint Hills or Oklahoma Osage hills using only time, sun position and a well-developed sense of direction. There were no water towers, power lines, hedge rows and only a few trails and dusty roads to assist with navigation. A few thoughts about the missionary trails of the Jesuits are discussed below:

The Adventurous, Romantic Lives of the Trail Riders.

There is little doubt that men like Fathers Paul Ponziglione or Philip Colleton were driven by the burning desire to spread God’s word, fueled by a dose of wanderlust. Not all priests were cut out to do the incessant traveling, planning and then riding again as a very small group of trail riders. There are paintings and statues of missionaries riding tall in the saddle with a prayer book in hand. Their day’s ride often ended, with head on saddle under a starlit sky—they did that. But those who imagine sleeping on the prairie probably don’t consider burrowing inside of a wool blanket on a 90 degree evening to escape an onslaught of hundreds of mosquitoes. They did that too!

It was hard, dirty, hazardous work. The priests spent much of their time in the saddle, or on a wagon seat behind a team of horses. Food was often a supply of dried biscuits and smoked meat packed among hosts, a chalice, a small oil lamp, prayer books and other things the rider might need to celebrate the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass or to read his prayers after dark. On one excursion to Wichita Father Ponziglione, dressed in boots, flannel shirt and broad hat was so caked with grime that locals considered driving the tramp out of town—luckily a Catholic familiar with the priest intervened.

During the late 1850’s through mid-60’s they had to be vigilant of roaming bands of Confederate guerillas or inebriated Union troops, either of which might decide to execute a stranger on the roadside. Horses went lame, wagon axles broke and illness could incapacitate. Father Colleton got caught in a hailstorm in 1869 and had to take shelter under his saddle to avoid injury. If a serious problem occurred, the lone rider had to solve it himself. Not doing so could be fatal.

There is little doubt that men like Fathers Paul Ponziglione or Philip Colleton were driven by the burning desire to spread God’s word, fueled by a dose of wanderlust. Not all priests were cut out to do the incessant traveling, planning and then riding again as a very small group of trail riders. There are paintings and statues of missionaries riding tall in the saddle with a prayer book in hand. Their day’s ride often ended, with head on saddle under a starlit sky—they did that. But those who imagine sleeping on the prairie probably don’t consider burrowing inside of a wool blanket on a 90 degree evening to escape an onslaught of hundreds of mosquitoes. They did that too!

It was hard, dirty, hazardous work. The priests spent much of their time in the saddle, or on a wagon seat behind a team of horses. Food was often a supply of dried biscuits and smoked meat packed among hosts, a chalice, a small oil lamp, prayer books and other things the rider might need to celebrate the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass or to read his prayers after dark. On one excursion to Wichita Father Ponziglione, dressed in boots, flannel shirt and broad hat was so caked with grime that locals considered driving the tramp out of town—luckily a Catholic familiar with the priest intervened.

During the late 1850’s through mid-60’s they had to be vigilant of roaming bands of Confederate guerillas or inebriated Union troops, either of which might decide to execute a stranger on the roadside. Horses went lame, wagon axles broke and illness could incapacitate. Father Colleton got caught in a hailstorm in 1869 and had to take shelter under his saddle to avoid injury. If a serious problem occurred, the lone rider had to solve it himself. Not doing so could be fatal.

Snow-Packed Trails.

Fathers Ponziglione and Colleton made long excursions during the winter months. Traveling could be miserable, but the likelihood of finding people at home was higher. One such excursion nearly took Father Paul’s life as described in Graves’ “Life and Letters of Fathers Ponziglione, Schoenmakers, ….”

Fathers Ponziglione and Colleton made long excursions during the winter months. Traveling could be miserable, but the likelihood of finding people at home was higher. One such excursion nearly took Father Paul’s life as described in Graves’ “Life and Letters of Fathers Ponziglione, Schoenmakers, ….”

“…. On one occasion he came near losing his life in a Kansas blizzard on the prairie between Winfield and Howard. In those days there were few fences and roads between towns were merely trails across the country. The good Father was on his way home from a long trip in the “southwest country” when a “northerner” came up, and with it came a driving snow which soon covered all traces of the trail. The broad prairie was one wide expanse of white. He was not very familiar with the country and lost his way. He kept driving but came in sight of no habitation. In due time his horses became so weary from the long trip in the storm that they could go no farther. They stopped in a valley with the back of the buggy to the wind that it might afford some protection from the storm. The Father was so cold he could do nothing for his horses. There he was out on the open prairie, he knew not where, with his horses exhausted, a storm raging and no aid in sight. Neither he nor his horses had anything to eat since morning, and night was coming on. There he sat in his buggy, telling his beads when Abe Steinberger, now of Oklahoma, but at that time a Kansas newspaper man, came along on his way to Howard from Winfield, driving a team of big horses. Mr. Steinberger told the writer of seeing the buggy a short distance off the trail and going to it. "The good Lord will take care of me," was the reply the Father gave his inquiry as to how he came to be there, but he was so cold he could hardly speak this loud enough to be heard in the storm. Mr. Steinberger helped the Father into his own buggy, wrapped him in a buffalo robe, tied his horses behind his buggy and proceeded to Howard. Half pulling the horses behind, they made slow progress but reached Howard just after dark. Father Ponziglione was put to bed in a hotel and given "hot drinks," and altho no serious results followed his experience, he was not able to proceed homeward for nearly a week.”

Iron Trails.

With the coming of railroads, the trail riders had the occasional luxury of a new means of travel. However two clips from Father Ponziglione's writings suggest he had some mixed feelings about the fledgling railroads:

“Since the introduction of railroads in this section of Kansas our way of travelling has changed considerably. Heretofore we went exclusively horseback, now however sometimes we travel as gentlemen in palatial cars.”

In another place he said: “ … travelling now becomes difficult, nay dangerous, and this especially upon our new rail-roads which are built rather superficially, in fact, here and there long tracks of grading are washed away, and bridges carried off, the result of this is that cars frequently run down from embankments and people are crippled and killed.”

This last clip leads to a discussion of a rail accident when a bridge on the Ouachita River [likely in Arkansas] washed out. The train, which was carrying a large number of construction laborers, and Father Colleton, derailed landing many of the men in the river. There were injuries and two fatalities, but another stout Irishman pulled Father Philip from the water by his collar. But Father Colleton’s railroad problems got much, much worse.

In a letter written in 1873 Father Ponziglione described a horrible accident that, again, involved Father Colleton. The priest was returning from Pueblo on a construction train loaded with 200 workers and equipment. They became snowbound in a blizzard on a stretch of rail between Fort Dodge and Fort Larned and subsisted for three days on scant provisions of biscuits and cheese. Finally, on day four, they were able to celebrate a break in weather and the crew prepared to depart. However, a second train appeared on the horizon and crashed engine-to-engine merging the two locomotives into a blazing inferno. Father Colleton was able to stay clear of the carnage and administered the Last Absolution to two crewmen as they burned to death in the tangled metal.

With the coming of railroads, the trail riders had the occasional luxury of a new means of travel. However two clips from Father Ponziglione's writings suggest he had some mixed feelings about the fledgling railroads:

“Since the introduction of railroads in this section of Kansas our way of travelling has changed considerably. Heretofore we went exclusively horseback, now however sometimes we travel as gentlemen in palatial cars.”

In another place he said: “ … travelling now becomes difficult, nay dangerous, and this especially upon our new rail-roads which are built rather superficially, in fact, here and there long tracks of grading are washed away, and bridges carried off, the result of this is that cars frequently run down from embankments and people are crippled and killed.”

This last clip leads to a discussion of a rail accident when a bridge on the Ouachita River [likely in Arkansas] washed out. The train, which was carrying a large number of construction laborers, and Father Colleton, derailed landing many of the men in the river. There were injuries and two fatalities, but another stout Irishman pulled Father Philip from the water by his collar. But Father Colleton’s railroad problems got much, much worse.

In a letter written in 1873 Father Ponziglione described a horrible accident that, again, involved Father Colleton. The priest was returning from Pueblo on a construction train loaded with 200 workers and equipment. They became snowbound in a blizzard on a stretch of rail between Fort Dodge and Fort Larned and subsisted for three days on scant provisions of biscuits and cheese. Finally, on day four, they were able to celebrate a break in weather and the crew prepared to depart. However, a second train appeared on the horizon and crashed engine-to-engine merging the two locomotives into a blazing inferno. Father Colleton was able to stay clear of the carnage and administered the Last Absolution to two crewmen as they burned to death in the tangled metal.

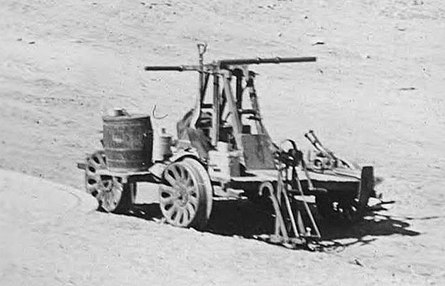

The push-bar of a simple handcar led to Father Philip's death.

The push-bar of a simple handcar led to Father Philip's death.

Having survived two train wrecks, the event that led to Father Colleton’s death seems cruelly ironic. On January 16, 1876 he was traveling between Parsons and Ladore on a common railroad handcar. The bar that propels the wheels struck him in the chest pushing him back into a metal tool chest. He was left unconscious and it was several days before he could return to the mission for medical care. On his return he was confined to his room under physician’s care for some time. He slowly began to recover and resume some of his work at the mission. On December 1, of 1876, Father Colleton died suddenly of an apparent hemorrhage.

In our present, cushy society that worships the ‘mental and physical toughness’ of obscenely paid athletes, neither they, nor we, can even imagine how tough these men were.

In our present, cushy society that worships the ‘mental and physical toughness’ of obscenely paid athletes, neither they, nor we, can even imagine how tough these men were.

Father Pierre Jean De Smet

Father Pierre Jean De Smet

Perspective

A curious fact that is disturbing—at least to me. Much of the Jesuit missionary work north of the Santa Fe Trail was done by Father Pierre Jean De Smet. Some of De Smet’s work was along the Missouri River corridor between St. Louis and the northwest United States. He also visited Kansas. In the areas where Father De Smet traveled there are many tributes to his name including a town, libraries, statues and at least one school. The name De Smet is almost synonymous with exploration, adventure and missionary persistence.

The work of the Catholic Mission Jesuits was no less important than De Smet’s labors; and the scope of their travels is also impressive, to say the least. They sowed the seeds of civilization in a very large area and assisted with the startup of many communities. They established churches, many of which nurtured schools. In fact, nearly all of the Catholic schools in the nine-county southeast Kansas area are linked to the Catholic Mission. They faced danger and they, too, were rigid in their determination to do the work of their church.

Then, why is it that here, in the hometown of their labors, our prairie missionaries are all but forgotten?

A curious fact that is disturbing—at least to me. Much of the Jesuit missionary work north of the Santa Fe Trail was done by Father Pierre Jean De Smet. Some of De Smet’s work was along the Missouri River corridor between St. Louis and the northwest United States. He also visited Kansas. In the areas where Father De Smet traveled there are many tributes to his name including a town, libraries, statues and at least one school. The name De Smet is almost synonymous with exploration, adventure and missionary persistence.

The work of the Catholic Mission Jesuits was no less important than De Smet’s labors; and the scope of their travels is also impressive, to say the least. They sowed the seeds of civilization in a very large area and assisted with the startup of many communities. They established churches, many of which nurtured schools. In fact, nearly all of the Catholic schools in the nine-county southeast Kansas area are linked to the Catholic Mission. They faced danger and they, too, were rigid in their determination to do the work of their church.

Then, why is it that here, in the hometown of their labors, our prairie missionaries are all but forgotten?

Also see this brief explaination of Missions, Stations and Churches.

Go to: 8. A Dangerous Balance - The Civil War (1861 - 1965) - or - Story

Go to: 8. A Dangerous Balance - The Civil War (1861 - 1965) - or - Story

Some Reference Information:

- Beacon on the Plains, Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald, St. Mary’s College, Leavenworth 1939 (Reprinted by Osage Mission Historical Society. (Appendix H of this book lists 113 Kansas Missions including Osage Mission.)

- The Jesuits of the Middle United States, Chapter 27, The Osage Mission. This is one chapter from a three-volume, forty-four chapter work that was published by Gilbert J. Garraghan, S. J. PhD in 1938. It is an incredible reference source. If you can find a hard copy it would probably be very expensive. Fortunately, it is available on-line: http://jesuitarchives.org/virtuallygarraghan/ (Select a chapter and it appears at the right of the screen. Then double click on the page image to download the chapter in PDF format.)

- Journal of the Western Missions Established and Attended by the Fathers of the Society of Jesus Residing at Osage Mission, Neosho County, Kansas, Transcribed by Reverend Eugene Grabner, Diocese of Wichita, 1995. This work is unpublished.

- Life and Letters of Fathers Ponziglione, Schoenmakers, and Other Early Jesuits at Osage Mission, William Whites Graves, 1916.

- The train wreck illustration was very heavily edited from a drawing of the Camp Hill disaster on the "Dangerous Crossings" page of the East Falls Local site. http://www.eastfallslocal.com/dangerous-crossings-railroads-19th-century/

- The hand-car photo is from Railroad Handcar History, http://www.railroadhandcar.com/. This is a pretty neat site for anyone interested in railroad, and especially handcar information. The website author, Mason Clark, builds and sells completed handcars and kits.

- The background map is a composite of six individual maps from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas, Austin. This collection provides a set of very uniformly drafted state maps showing counties, county seats, major water features, etc. Maps of Kansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, Colorado and New Mexico were digitally stitched together and edited to add the Santa Fe Trail, forts and the Jesuit missions. A cutout from this same map is used in 7.A. All six maps are "Base Maps" from the University website: https://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/united_states.html