Above - May 31 Banquet in St. Paul Kansas.

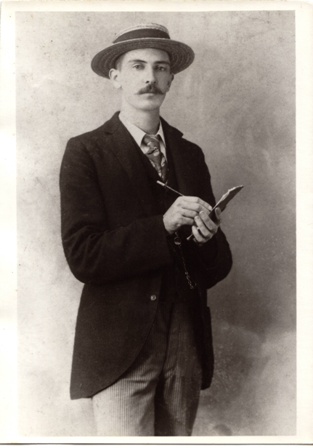

William Whites Graves - The Man of the Journal.

"I have never put out a book for which I entertained any prospects of monetary reward. I have always written because I couldn't help doing it; it has been the accolade of earthly happiness to be engaged in assembling data for another book." William Whites (W. W.) Graves

William Whites Graves - The Man of the Journal.

"I have never put out a book for which I entertained any prospects of monetary reward. I have always written because I couldn't help doing it; it has been the accolade of earthly happiness to be engaged in assembling data for another book." William Whites (W. W.) Graves

W. W. Graves’ photo appeared front-page-center on the July 24, 1952 issue of the St. Paul Journal. The obituary that followed started: “Death took this community’s most esteemed and honored citizen Tuesday evening.” Mr. Graves sudden death sent a shock wave through the community. The grand old scholar’s health had been in decline for years, but his death was a surprise. During his honors banquet, only weeks before, he was happy, appreciative and characteristically modest. But he was frail. Members of the local and statewide community felt fortunate they were able to honor him before he passed. The introduction to his obituary was written with purpose. Few men have received the level of respect that Graves received at the banquet.

Graves' birthplace near Manton and Bear Wallow, Kentucky shared many similarities with Osage Mission/St. Paul. The Osage Mission Loretto Sisters were from nearby Nerinx. Holy Cross Catholic Church, just south of Manton, was a founding center of Catholicism. Two of his aunts were Lorettos.

Graves' birthplace near Manton and Bear Wallow, Kentucky shared many similarities with Osage Mission/St. Paul. The Osage Mission Loretto Sisters were from nearby Nerinx. Holy Cross Catholic Church, just south of Manton, was a founding center of Catholicism. Two of his aunts were Lorettos.

Kentucky Roots:

William Whites Graves was the oldest of nine children of John Paul (J. P.) and Minerva Ballard Graves. Two siblings died young—one in Kentucky, one in Kansas. He was born on a farm in the moonshine district of Kentucky on October 26, 1871. Much of his Kentucky life is traced to the three central Kentucky counties of Nelson, Marion and Washington; and many of the prominent locations and events he talked about later occurred near the hamlet of Manton, Kentucky. Graves’ middle name “Whites (or Wuyts?)” was the name of the pastor of the Holy Rosary Catholic Church in Manton where he was baptized. The “moonshine district” was in and east of the counties mentioned above and that area has flourished into Kentucky’s premium bourbon production region. But distilled liquor would not be the spirit that held Graves’ attention for most of his life. He would focus much of his attention on the courage and spirituality of a group of Loretto sisters who traveled from nearby Nerinx to Kansas twenty-four years before his birth. A missionary sister from Nerinx was the subject of one of his several books (Mother Bridget Hayden).

William Whites Graves was the oldest of nine children of John Paul (J. P.) and Minerva Ballard Graves. Two siblings died young—one in Kentucky, one in Kansas. He was born on a farm in the moonshine district of Kentucky on October 26, 1871. Much of his Kentucky life is traced to the three central Kentucky counties of Nelson, Marion and Washington; and many of the prominent locations and events he talked about later occurred near the hamlet of Manton, Kentucky. Graves’ middle name “Whites (or Wuyts?)” was the name of the pastor of the Holy Rosary Catholic Church in Manton where he was baptized. The “moonshine district” was in and east of the counties mentioned above and that area has flourished into Kentucky’s premium bourbon production region. But distilled liquor would not be the spirit that held Graves’ attention for most of his life. He would focus much of his attention on the courage and spirituality of a group of Loretto sisters who traveled from nearby Nerinx to Kansas twenty-four years before his birth. A missionary sister from Nerinx was the subject of one of his several books (Mother Bridget Hayden).

To Kansas in 1881:

In February of 1881 his family took the leap of faith that many were taking and moved to the Kansas Frontier. His Kentucky background plus the things he witnessed during the 10-15 years after his arrival in Osage Mission left a defining impression on him. During the following seventy years Graves became a father of his new community; and a prominent literary figure.

Graves continued his education in the new Osage Mission public schools. At some point the administrator of the local Jesuit boarding college took notice of the young man and offered him free tuition if he wanted to finish his education. He jumped on the offer and graduated from St. Francis Institute, with honors, in the spring of 1892. He later wrote that St. Francis instilled a spirit of rivalry and competition that served him for life.

In February of 1881 his family took the leap of faith that many were taking and moved to the Kansas Frontier. His Kentucky background plus the things he witnessed during the 10-15 years after his arrival in Osage Mission left a defining impression on him. During the following seventy years Graves became a father of his new community; and a prominent literary figure.

Graves continued his education in the new Osage Mission public schools. At some point the administrator of the local Jesuit boarding college took notice of the young man and offered him free tuition if he wanted to finish his education. He jumped on the offer and graduated from St. Francis Institute, with honors, in the spring of 1892. He later wrote that St. Francis instilled a spirit of rivalry and competition that served him for life.

Reporter Graves:

After graduation, he tried teaching for a while and worked in his father’s Osage Mission store. Neither provided satisfaction. He decided he wanted to be a printer and newspaper man. In May of 1893 he worked briefly for the Fort Scott Lantern and then moved south to secure an apprenticeship with the Pittsburg World. His introduction to the trade was rocky. Pittsburg was a much larger town, the population was largely immigrant and he had trouble adapting to the new assignment. His boss, Abe Steinberger, decided to send him to the Girard desk where Graves excelled as a reporter and he also picked up some editing duties. Then, the World moved to Girard where he became one of Steinberger’s valued employees. His job with the World took on another positive aspect. He met World bookkeeper Emma Hopkins and they were married on May 1, 1895. But early married bliss hit a bump in November of 1895 when the paper folded and both of the Graves’s were unemployed.

Graves admits that much of his success in life came from opportunity and some of his opportunities were probably luck. The timing of his unemployment led to the luckiest opportunity of his life. Within two months of his termination, he was offered the opportunity to buy The Neosho County Journal (formerly Osage Mission Journal). A friend, B. B. Fitzsimmons, assisted with financing and within four years the twenty-nine year old editor owned his own small town newspaper business. Graves eventually changed the name of the paper to The St. Paul Journal in April of 1901.

After graduation, he tried teaching for a while and worked in his father’s Osage Mission store. Neither provided satisfaction. He decided he wanted to be a printer and newspaper man. In May of 1893 he worked briefly for the Fort Scott Lantern and then moved south to secure an apprenticeship with the Pittsburg World. His introduction to the trade was rocky. Pittsburg was a much larger town, the population was largely immigrant and he had trouble adapting to the new assignment. His boss, Abe Steinberger, decided to send him to the Girard desk where Graves excelled as a reporter and he also picked up some editing duties. Then, the World moved to Girard where he became one of Steinberger’s valued employees. His job with the World took on another positive aspect. He met World bookkeeper Emma Hopkins and they were married on May 1, 1895. But early married bliss hit a bump in November of 1895 when the paper folded and both of the Graves’s were unemployed.

Graves admits that much of his success in life came from opportunity and some of his opportunities were probably luck. The timing of his unemployment led to the luckiest opportunity of his life. Within two months of his termination, he was offered the opportunity to buy The Neosho County Journal (formerly Osage Mission Journal). A friend, B. B. Fitzsimmons, assisted with financing and within four years the twenty-nine year old editor owned his own small town newspaper business. Graves eventually changed the name of the paper to The St. Paul Journal in April of 1901.

Another Opportunity!

And then opportunity knocked again—LOUD! The Anti-Horse Thief Association (A.H.T.A.) was a well-respected volunteer vigilance organization that wanted to improve it's multi-state communications. In 1901 Graves was given an opportunity to bid a lucrative contract to start and publish the A.H.T.A. Weekly newspaper. In spite of being woefully short of printing capacity, he won. This contract provided revenue to move to a larger shop, and gradually grow his business. It also gave him a great deal of influence with the A.H.T.A. During the early 1900’s he also secured contracts with the Knights of Columbus and other groups for publishing their papers. Graves’ Journal Publishing grew into one of the most modern printing and publishing plants in the area.

Historian-Publisher Graves.

Becoming a publisher fit another vocation well. He was a writer and he loved history. He also had a deep Catholic faith. During the early 1900’s he almost certainly compared details of his Kentucky roots with his local experience. The Manton-Bardstown area and the Osage Catholic Mission were both birthplaces of Catholicism and civilization in their respective areas; and some of the same historical characters had been at both places [1]. He dedicated much of his life to telling the story of the Osage, the Jesuits, the Lorettos and the early growth of southern Kansas. In doing so he published or co-published a series of books or publications—most about the works of the church in early Kansas. [2] He and Emma were founding members of the original Neosho County Historical Society and the Kansas Catholic Historical Society. Graves also submitted countless articles to the Kansas State Historical Society. He worked tirelessly to preserve the history of his church and in 1952 the Vatican responded.

And then opportunity knocked again—LOUD! The Anti-Horse Thief Association (A.H.T.A.) was a well-respected volunteer vigilance organization that wanted to improve it's multi-state communications. In 1901 Graves was given an opportunity to bid a lucrative contract to start and publish the A.H.T.A. Weekly newspaper. In spite of being woefully short of printing capacity, he won. This contract provided revenue to move to a larger shop, and gradually grow his business. It also gave him a great deal of influence with the A.H.T.A. During the early 1900’s he also secured contracts with the Knights of Columbus and other groups for publishing their papers. Graves’ Journal Publishing grew into one of the most modern printing and publishing plants in the area.

Historian-Publisher Graves.

Becoming a publisher fit another vocation well. He was a writer and he loved history. He also had a deep Catholic faith. During the early 1900’s he almost certainly compared details of his Kentucky roots with his local experience. The Manton-Bardstown area and the Osage Catholic Mission were both birthplaces of Catholicism and civilization in their respective areas; and some of the same historical characters had been at both places [1]. He dedicated much of his life to telling the story of the Osage, the Jesuits, the Lorettos and the early growth of southern Kansas. In doing so he published or co-published a series of books or publications—most about the works of the church in early Kansas. [2] He and Emma were founding members of the original Neosho County Historical Society and the Kansas Catholic Historical Society. Graves also submitted countless articles to the Kansas State Historical Society. He worked tirelessly to preserve the history of his church and in 1952 the Vatican responded.

Businessman Graves.

Graves was a small-town newspaperman, publisher for state and national newspaper customers, historian and writer. But he had many other irons in the fire. He and his partner/brother-in-law A. J. Hopkins started three theaters in St. Paul—one outdoor and two in structures they built. He had his own electrical plant for the Journal office and theater ten years before St. Paul had a municipal grid. He owned part-interest in the local Sork Harness Shop. He and Ed George sold Maxwell motor cars for a while. He also dabbled in real estate. Property and casualty insurance was a sideline business for much of his life. Some businesses came and went; and in some cases he invested starting capital for a local business and then stepped back. He was a model of a post-frontier era entrepreneur.

Emma and W.W. were also active and generous with their church. In 1903 W.W. was a charter officer of Knights of Columbus Council 760. Three years later he took the lead when the council commissioned a portrait of Father Paul Ponziglione with Chicago artist Edgar Leon. This painting was displayed in St. Paul for a short time and then donated to the Kansas State Historical Society. In 1932 they donated a new public address system for St. Francis Church; and they provided printing services to the church. But Graves’ main act of stewardship was his work to record the growth of the Catholic Church in Kansas.

Hard Times and Tragedy.

To say that W.W. Graves stayed busy is a pretty obvious understatement—perhaps too busy. As early as 1913 he was fighting gastric ulcers. There are several mentions of illness and at one point illness affected his A.H.T.A. weekly contract. 1936 was a catastrophic year. In May he was hospitalized for more than a month after a serious operation. Later that month Emma had what appeared to be a minor heart attack. But on July 30 she died. W.W. Graves’ soulmate and partner—the woman who often set type in the home kitchen during their early years—was suddenly gone after 42 years of marriage.

Emma’s death might have knocked some wind from his sails. While he stayed active in civic affairs, he started slowly divesting some business interests. He had already sold his interest in the A.H.T.A. Weekly in 1932 and he sold his subscription list for the Knights of Columbus newspaper in 1938. He even began thinking about the sale or lease of his St. Paul Journal. But he stayed very active with his writing and publishing.

His Later Years.

In 1941 W.W. married again. Susie Gibbons was a good friend of the Graves’s and assisted with the founding the Neosho County Historical Society. Like W.W., she had been involved in civic affairs and served as the local postmaster for several years. Susie set up a gift and card shop in the front of the Journal office that she ran for years. She never replaced Emma’s memory, but Susie might have shared some of the soulmate position in Graves’ final years.

By the late 1940’s Graves’ health was in steady decline. He fought the effects of arterial sclerosis for years and in July of 1950 he traveled to Kenosha, Wisconsin to have his right foot amputated. But his mind and enthusiasm remained active. A month before the amputation he kicked off his city library project with a Journal article: “A Modern City.” He emphasized the need for a library by pledging books and a bookcase from his personal collection to seed the project. He closed the article with an admonishment: "Now is the time. Now, not next year! The Journal man may not be on earth then, hence do not delay too long.” The urgency was clear—W.W. knew he might not finish this job. But then he enlisted the local Home Demonstration Units to run his project knowing that when these teams of women got their teeth into it, his job would get done. In a January 11, 1951 Journal article he said:

“It is expected that some real progress will be forthcoming now concerning a new Public Library for St. Paul. The various Home Demonstration units in the community are checking into the matter and this sheet has always predicted that when the women start a project it goes over in a big way. Now let's all boost for a Public Library for this community.”

In those days many Home Demonstration Units served as very effective project management teams; and the local women stepped up and got the job done! But Graves' premonition was correct—he didn't see the project to completion.

Graves was a small-town newspaperman, publisher for state and national newspaper customers, historian and writer. But he had many other irons in the fire. He and his partner/brother-in-law A. J. Hopkins started three theaters in St. Paul—one outdoor and two in structures they built. He had his own electrical plant for the Journal office and theater ten years before St. Paul had a municipal grid. He owned part-interest in the local Sork Harness Shop. He and Ed George sold Maxwell motor cars for a while. He also dabbled in real estate. Property and casualty insurance was a sideline business for much of his life. Some businesses came and went; and in some cases he invested starting capital for a local business and then stepped back. He was a model of a post-frontier era entrepreneur.

Emma and W.W. were also active and generous with their church. In 1903 W.W. was a charter officer of Knights of Columbus Council 760. Three years later he took the lead when the council commissioned a portrait of Father Paul Ponziglione with Chicago artist Edgar Leon. This painting was displayed in St. Paul for a short time and then donated to the Kansas State Historical Society. In 1932 they donated a new public address system for St. Francis Church; and they provided printing services to the church. But Graves’ main act of stewardship was his work to record the growth of the Catholic Church in Kansas.

Hard Times and Tragedy.

To say that W.W. Graves stayed busy is a pretty obvious understatement—perhaps too busy. As early as 1913 he was fighting gastric ulcers. There are several mentions of illness and at one point illness affected his A.H.T.A. weekly contract. 1936 was a catastrophic year. In May he was hospitalized for more than a month after a serious operation. Later that month Emma had what appeared to be a minor heart attack. But on July 30 she died. W.W. Graves’ soulmate and partner—the woman who often set type in the home kitchen during their early years—was suddenly gone after 42 years of marriage.

Emma’s death might have knocked some wind from his sails. While he stayed active in civic affairs, he started slowly divesting some business interests. He had already sold his interest in the A.H.T.A. Weekly in 1932 and he sold his subscription list for the Knights of Columbus newspaper in 1938. He even began thinking about the sale or lease of his St. Paul Journal. But he stayed very active with his writing and publishing.

His Later Years.

In 1941 W.W. married again. Susie Gibbons was a good friend of the Graves’s and assisted with the founding the Neosho County Historical Society. Like W.W., she had been involved in civic affairs and served as the local postmaster for several years. Susie set up a gift and card shop in the front of the Journal office that she ran for years. She never replaced Emma’s memory, but Susie might have shared some of the soulmate position in Graves’ final years.

By the late 1940’s Graves’ health was in steady decline. He fought the effects of arterial sclerosis for years and in July of 1950 he traveled to Kenosha, Wisconsin to have his right foot amputated. But his mind and enthusiasm remained active. A month before the amputation he kicked off his city library project with a Journal article: “A Modern City.” He emphasized the need for a library by pledging books and a bookcase from his personal collection to seed the project. He closed the article with an admonishment: "Now is the time. Now, not next year! The Journal man may not be on earth then, hence do not delay too long.” The urgency was clear—W.W. knew he might not finish this job. But then he enlisted the local Home Demonstration Units to run his project knowing that when these teams of women got their teeth into it, his job would get done. In a January 11, 1951 Journal article he said:

“It is expected that some real progress will be forthcoming now concerning a new Public Library for St. Paul. The various Home Demonstration units in the community are checking into the matter and this sheet has always predicted that when the women start a project it goes over in a big way. Now let's all boost for a Public Library for this community.”

In those days many Home Demonstration Units served as very effective project management teams; and the local women stepped up and got the job done! But Graves' premonition was correct—he didn't see the project to completion.

Honoring Our Community's Most Esteemed Citizen.

The eastern Kansas historical and literary communities also knew Mr. Graves health was failing; and he deserved recognition. On May 31, 1952, representatives from the State of Kansas, the eastern Kansas publishing community, the Osage Nation, the Roman Catholic Church and his beloved St. Paul gathered to honor him in a banquet. The banquet was held in the St. Francis school gymnasium. There were many speeches and accolades delivered along with some roasting. Two of the honors presented to William Graves that evening rank as extraordinary:

The eastern Kansas historical and literary communities also knew Mr. Graves health was failing; and he deserved recognition. On May 31, 1952, representatives from the State of Kansas, the eastern Kansas publishing community, the Osage Nation, the Roman Catholic Church and his beloved St. Paul gathered to honor him in a banquet. The banquet was held in the St. Francis school gymnasium. There were many speeches and accolades delivered along with some roasting. Two of the honors presented to William Graves that evening rank as extraordinary:

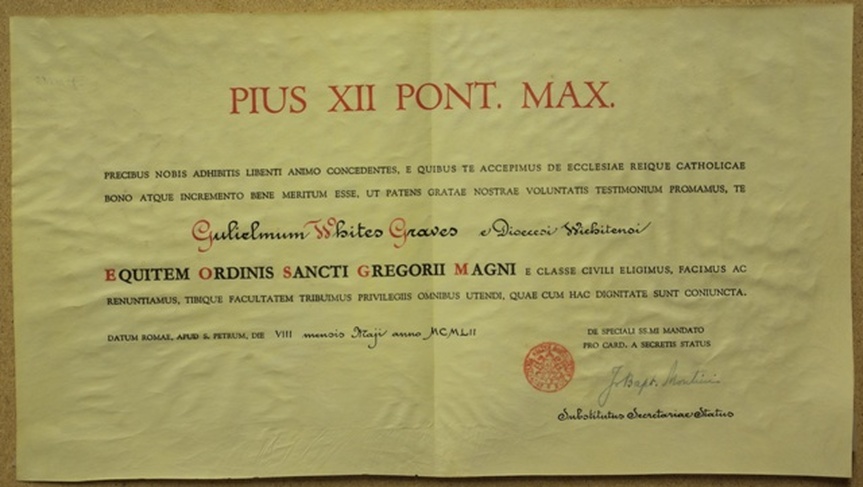

- Bishop Mark K. Carroll of Wichita, on the behalf of Pope Pius XII, presented Graves with a Vatican Knighthood of the Order of St. Gregory. This knighthood is the highest honor possible for a Catholic layman. The knighthood was bestowed in recognition of Graves’ efforts in preserving the work of the Osage Mission missionaries in service of the Osage people; and the Jesuit missionary work across the regional frontier. Receiving this recognition placed Mr. Graves in the company of: Eunice Kennedy Shriver, Rupert Murdoch, and Ricardo Montalbán.

Grave's Headdress is displayed at the Osage Mission - Neosho County Museum. (Click)

Grave's Headdress is displayed at the Osage Mission - Neosho County Museum. (Click)

- He was also made an honorary Chief of the Osage Tribe. This included a beautiful Osage chief’s headdress. The presentation was made by Fred Lookout Jr., son of the late, famous Osage Chief Fred Lookout, who was also a close, personal friend of Graves. Tribal membership honors are presented more frequently but Chief distinction, especially presented to a white man, was a rare honor. The Osage presentation also proclaimed Graves as “Wy-La-Za-XaNe-Ka-Zhin which was interpreted by his Osage brothers as “Mr. Man of the Journal”. Both honors were in recognition of Graves’ friendship with the tribe and his efforts to tell the story of the Osages during their time in Kansas.

It can be argued that the prestige of the Vatican knighthood carried more weight than any of the honors of the evening. But the writer has to believe that being recognized as the “Man of the Journal” by his Osage brothers might have given him a special sense of pride and accomplishment. It was the story of the Osage and the Mission to which he devoted much of his life; and the Journal would always be “his” newspaper.

On July 22, 1952 William Whites Graves collapsed and died of a heart attack at his home. The honor and esteem that he received only seven weeks earlier were a testament to a life lived well—very well indeed!

The Vatican Scroll of Knighthood presented to W. W. Graves on May 31, 1952 by Bishop Mark K. Carroll. The medal show above is not Mr. Graves' medal. It has been lost. (The scroll is a photograph of the original that is on-file at the Osage Mission - Neosho County Historical Society. It is part of the Graves-Hopkins Collection archived in 2014.)

Some Reference Information:

[1] Fathers Paul Ponziglione and Philip Colleton both spent time at Bardstown before going to Osage Mission.

[1] Fathers Paul Ponziglione and Philip Colleton both spent time at Bardstown before going to Osage Mission.

- Newspaper scans and photographs are from copies on file at the Osage Mission - Neosho County Historical Society, St. Paul, Kansas.

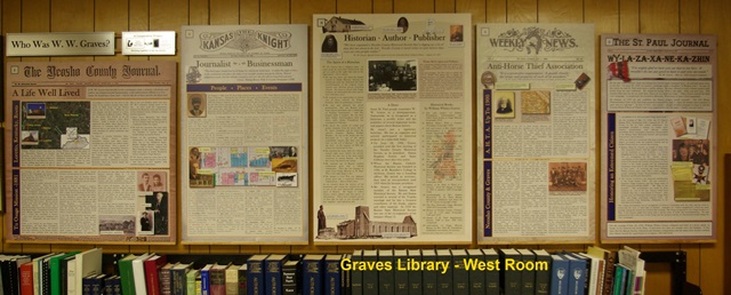

- Much of the information on this page was compiled during a research project done for the Graves Memorial Public Library in 2013. The purpose of the project was the development of a five-panel interpretive display on the life and times of W. W. Graves. Research, layout and editing was done by my wife and I with a lot of valuable help from Jane Ann Beachner. Thanks to Lon Smith and the library board for supporting the project. Some photos are shown below.

2. His Historical and Personal Works.

This is a partial list of his historical books and personal publications.

This is a partial list of his historical books and personal publications.

- Life and Letters of Fathers Ponziglione, Schoenmakers and Other Early Jesuits at Osage Mission (Copyright 1916)

- Making Money With a Country Newspaper (Copyright 1926)

- Life and Letters of Rev. Father John Schoenmakers S. J., Apostle to the Osages (Copyright 1928)

- Annals of Osage Mission (Copyright 1934)

- The Broken Treaty: A Story of Osage Country (Copyright 1935)

- The Legend of Greenbush: The Story of a Pioneer Country Church (Copyright 1937)

- The Life and Times of Mother Bridget Hayden (Copyright 1938)

- History of Neosho County Newspapers (Copyright 1938)

- The Poet Priest of Kansas, Father Thomas Aloysius McKernan (Copyright 1937)

- History of the Kickapoo Mission and Parish, The First Catholic Church in Kansas – Jointly published by W. W. Graves, Rev. Gilbert J. Garraghan, S. J., and Rev. George Towle (Copyright 1938)

- Annals of St. Paul: A Third of a Century. From the Change of Name in 1895 to January 1929 (Copyright 1942)

- Autobiography of Rev. Eugene Bononcini, D. D.: Early Kansas Missionary; Additions and Notes by W. W. Graves (Copyright 1942)

- The First Protestant Osage Missions 1820-1837 (Copyright 1949)

- History of Neosho County, Volumes I and II, 1,141 pages (Copyright 1949 and 1951)

- Annals of St. Paul: Supplement, January 1929 to June 1936 (Not completed)

- Antecedents of Osage Mission Kansas by Rev. Paul M. Ponziglione (published, not written, by Graves)