4. Earliest Protestant Missions.

“After eleven or twelve years of effort, the Protestant Missions were closed. Without a doubt the missionaries felt they had failed. Surely, they did not bring the Osages to the unrealistic heights of the missionary dreams. Yet, they accomplished a very difficult feat. They exposed the Osages to a part of the Euro-American culture that had never before been seen by the Osages. It is a shame that the missionaries were so self righteous and placed such strong stress on buildings and fields and not on humanity”

Louis F. Burns, A History of the Osage People, 1989

“After eleven or twelve years of effort, the Protestant Missions were closed. Without a doubt the missionaries felt they had failed. Surely, they did not bring the Osages to the unrealistic heights of the missionary dreams. Yet, they accomplished a very difficult feat. They exposed the Osages to a part of the Euro-American culture that had never before been seen by the Osages. It is a shame that the missionaries were so self righteous and placed such strong stress on buildings and fields and not on humanity”

Louis F. Burns, A History of the Osage People, 1989

In chapter 10 “The Search for Comprehension” of Louis Burns' book (above) he describes the efforts of the Protestant missionaries, and then the Catholics, in converting and civilizing his people. In reading his work and the work of W.W. Graves and others, some things stand out:

- Organized missionary initiatives among the Osage were sponsored by two groups—earlier efforts by eastern Protestant missionary organizations; and the later efforts were by the Jesuits. But an overriding influence was the government’s desire to civilize the tribes. Missionaries were another tool to deal with the ‘Indian problem.’

- Adding to the above, the missionary movement was not spontaneous. It was requested. The Osage realized that in order to succeed in the white man’s world their young should be educated. In September of 1819 a delegation of Claremore’s bands submitted a final request for mission educators and mission activity started the next year.

- To say that the Catholics excelled where the Protestants failed is a little harsh. Both the Protestants and Catholics were able to teach Osage who wanted to learn. Many resisted the Protestant methods. The Catholics did a better job of respecting the Osage beliefs and tailored much of their work to their needs--but with great frustration. As far as conversion to Christianity goes, the Jesuit successes were marginally better.

The Problems.

The Protestant missionaries had to contend with many issues. Some were beyond their control and others could have been dealt with through compromise. But there were few signs of negotiation or concession to the Osages desires:

The Protestant Missionaries were there first. Other than earlier encounters with the Jesuits; the Protestants launched the first organized attempt to convert and educate the Osages. Their inexperience with the harshness of the frontier and the culture of the western tribes compounded the next problem.

Many of the missionaries were inflexible and intolerant. The initial Protestant efforts were led by the United Foreign Missionary Society which later merged with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Much of the influence, and the missionary workforce, came from New York and Connecticut. Their ranks were controlled by the Presbyterians, Congregational and Dutch Reformed Churches acting together; but the missions were generally called Presbyterian. Given the times and beliefs, the mindset of the missionaries were puritanical. Conversion of the savages to Christianity was priority number one and education was next. Thrusting the puritanical Presbyterians into the Osage culture produced culture shock in huge proportions. The Osage practiced polygamy. Horse theft was routine and intolerable. The Osage were militant and would settle differences with opposing tribes brutally. Their manner of dress, or undress, was inexcusable. The Protestants approached these issues with the intent of expunging elements of the Osage culture and turning them into white people. This was a non-starter for the Osages.

The missionaries insisted that teaching agriculture was essential. This led to two problems: First, the Osage had no interest in the labors of farming. Perhaps if the missionaries had blended ranching into the scheme, to match the Indians respect for animals, they would have been more successful. Second, agriculture was the enemy of the Osages fur trading partners. Increased agriculture, at the expense of the hunt, affected the trader’s revenue. The missionaries clashed with the traders, with Mission Neosho (discussed below) being a good example.

The Protestant missionaries had to contend with many issues. Some were beyond their control and others could have been dealt with through compromise. But there were few signs of negotiation or concession to the Osages desires:

The Protestant Missionaries were there first. Other than earlier encounters with the Jesuits; the Protestants launched the first organized attempt to convert and educate the Osages. Their inexperience with the harshness of the frontier and the culture of the western tribes compounded the next problem.

Many of the missionaries were inflexible and intolerant. The initial Protestant efforts were led by the United Foreign Missionary Society which later merged with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Much of the influence, and the missionary workforce, came from New York and Connecticut. Their ranks were controlled by the Presbyterians, Congregational and Dutch Reformed Churches acting together; but the missions were generally called Presbyterian. Given the times and beliefs, the mindset of the missionaries were puritanical. Conversion of the savages to Christianity was priority number one and education was next. Thrusting the puritanical Presbyterians into the Osage culture produced culture shock in huge proportions. The Osage practiced polygamy. Horse theft was routine and intolerable. The Osage were militant and would settle differences with opposing tribes brutally. Their manner of dress, or undress, was inexcusable. The Protestants approached these issues with the intent of expunging elements of the Osage culture and turning them into white people. This was a non-starter for the Osages.

The missionaries insisted that teaching agriculture was essential. This led to two problems: First, the Osage had no interest in the labors of farming. Perhaps if the missionaries had blended ranching into the scheme, to match the Indians respect for animals, they would have been more successful. Second, agriculture was the enemy of the Osages fur trading partners. Increased agriculture, at the expense of the hunt, affected the trader’s revenue. The missionaries clashed with the traders, with Mission Neosho (discussed below) being a good example.

Union Mission, 1820 – 1836.

Using today’s landmarks Union Mission was on the west bank of the Neosho-Grand River in extreme south Mayes County Oklahoma; or about fifteen miles north of Fort Gibson. It was the first of the Osage Missions and it opened with some fanfare. Mission Physician Dr. Marcus Palmer described the mission site

“The place chosen is fine prairie, containing eight hundred or a thousand acres of land, fringed around with woods. On one side flows Grand River, a rapid stream. In this are to be found a considerable abundance of wild horses, buffalo's, elk, bear, wolves, deer, panthers, swan, geese, ducks, turkeys and honey. About a mile distant is a salt spring, which will be wrought this season.”

Other missionaries wrote similar descriptions expressing delight with the site and high expectations for success. The initial “family” of Union missionaries included seventeen people, all from New York and Connecticut. Their skill-set included ministers, a physician, carpenters, farmers and some members with multiple skills such as farmers with stone-cutting, teaching, carpenter or blacksmith skills. Among them were eight women, two of which were married to team members.

Union had the longest service of the Neosho River missions. They certainly had some successes with educating the young Indian children and marginal success with conversions. However, warfare between the Osage and Cherokees disrupted continuity and the Osage adults did not trust the missionaries to keep their children safe. The effects of the Treaty of 1825 moved the Osages farther from the mission. By 1833 educational efforts subsided but the substantial investment in property and buildings led the American Board of Commissioners to maintain the site as a publishing plant for production of religious materials. This work was abandoned in December of 1936.

It should be noted here that the mission startups north of Union were not isolated events. Some members of the Union family moved north; and people like Union Mission farmer and teacher William Requa were instrumental with northern missions.

Using today’s landmarks Union Mission was on the west bank of the Neosho-Grand River in extreme south Mayes County Oklahoma; or about fifteen miles north of Fort Gibson. It was the first of the Osage Missions and it opened with some fanfare. Mission Physician Dr. Marcus Palmer described the mission site

“The place chosen is fine prairie, containing eight hundred or a thousand acres of land, fringed around with woods. On one side flows Grand River, a rapid stream. In this are to be found a considerable abundance of wild horses, buffalo's, elk, bear, wolves, deer, panthers, swan, geese, ducks, turkeys and honey. About a mile distant is a salt spring, which will be wrought this season.”

Other missionaries wrote similar descriptions expressing delight with the site and high expectations for success. The initial “family” of Union missionaries included seventeen people, all from New York and Connecticut. Their skill-set included ministers, a physician, carpenters, farmers and some members with multiple skills such as farmers with stone-cutting, teaching, carpenter or blacksmith skills. Among them were eight women, two of which were married to team members.

Union had the longest service of the Neosho River missions. They certainly had some successes with educating the young Indian children and marginal success with conversions. However, warfare between the Osage and Cherokees disrupted continuity and the Osage adults did not trust the missionaries to keep their children safe. The effects of the Treaty of 1825 moved the Osages farther from the mission. By 1833 educational efforts subsided but the substantial investment in property and buildings led the American Board of Commissioners to maintain the site as a publishing plant for production of religious materials. This work was abandoned in December of 1936.

It should be noted here that the mission startups north of Union were not isolated events. Some members of the Union family moved north; and people like Union Mission farmer and teacher William Requa were instrumental with northern missions.

Painting of Harmony Mission by Mrs. Lucille Stevener from the memory of J.R. Barrow who lived at Harmony when the building was standing.

Painting of Harmony Mission by Mrs. Lucille Stevener from the memory of J.R. Barrow who lived at Harmony when the building was standing.

Harmony Mission (Missouri), 1821 – 1836.

The establishment of Harmony Mission in Bates County, Missouri, was a reaction to Union Mission. The Osages who remained in Missouri were envious of their brothers on the Arkansas and requested similar treatment. In March of 1821 another mission family assembled in New York for farewell services and the team departed four days later. The group consisted of eighteen missionaries plus family members. They were led by Superintendent Rev. Nathaniel Dodge and Assistant Superintendent Rev. Benton Pixley.

Harmony Mission was located on the bank of the Marais des Cygne near its juncture with the Osage-Marmaton. Harmony had the second longest term of the Protestant missions and the words “content” and “happy” appear in descriptions of the mission’s operations. But three factors brought it to an end: 1) As with Union, the Treaty of 1825 began to draw the Osage away. Even though some lagged behind, enrollments declined; 2) The factory-fort system of trading was closed by the government. This gave traders free hand to deal with the Osage, often convincing them to spend more time on the hunt; and many of the Indians insisted on taking their children with them. It also drew the Indians away from the agricultural interests of the missionaries. 3) Efforts of Indian Agents to mass Indians in villages were in direct opposition with missionary plans to disperse families on agricultural plots. The conflict between the missionaries desire to promote farming with the Indian’s (and traders) desire to extend the hunts were impracticable. Harmony suspended operations in 1836 after enrollment dwindled to less than 30 students.

The establishment of Harmony Mission in Bates County, Missouri, was a reaction to Union Mission. The Osages who remained in Missouri were envious of their brothers on the Arkansas and requested similar treatment. In March of 1821 another mission family assembled in New York for farewell services and the team departed four days later. The group consisted of eighteen missionaries plus family members. They were led by Superintendent Rev. Nathaniel Dodge and Assistant Superintendent Rev. Benton Pixley.

Harmony Mission was located on the bank of the Marais des Cygne near its juncture with the Osage-Marmaton. Harmony had the second longest term of the Protestant missions and the words “content” and “happy” appear in descriptions of the mission’s operations. But three factors brought it to an end: 1) As with Union, the Treaty of 1825 began to draw the Osage away. Even though some lagged behind, enrollments declined; 2) The factory-fort system of trading was closed by the government. This gave traders free hand to deal with the Osage, often convincing them to spend more time on the hunt; and many of the Indians insisted on taking their children with them. It also drew the Indians away from the agricultural interests of the missionaries. 3) Efforts of Indian Agents to mass Indians in villages were in direct opposition with missionary plans to disperse families on agricultural plots. The conflict between the missionaries desire to promote farming with the Indian’s (and traders) desire to extend the hunts were impracticable. Harmony suspended operations in 1836 after enrollment dwindled to less than 30 students.

Hopefield Mission #1, 1823 – 1830.

Hopefield Mission was not a new initiative; rather it was an extension of the Union Mission. Located about four miles north of Union, and on the opposite side of the Neosho-Grand River, it was an experiment. The Union missionaries concluded that the hunts of the Indians were often not successful and that game was becoming scarcer and farther away each year. Famine was inevitable unless things changed. Also, the longer hunts took young students from the schools. A missionary farm seemed to be a solution and William Requa and Rev. Chapman from Union were chosen to lead the effort.

The mission farm started with enthusiasm but it was initially poorly equipped. By the time it started, some of the Indian families were already in the grip of the feared famine due to poor hunting. But a group of the Osage did take to the labors of agriculture and the plot produced well. This encouraged other members of the tribe to join the mission. However a severe flood in 1826 dampened enthusiasm and worse was to come for the first location. A treaty in 1828 placed Hopefield within the Cherokee Nation and they were not willing to allow the mission to continue. This initiated Hopefield #2 (below).

Hopefield Mission was not a new initiative; rather it was an extension of the Union Mission. Located about four miles north of Union, and on the opposite side of the Neosho-Grand River, it was an experiment. The Union missionaries concluded that the hunts of the Indians were often not successful and that game was becoming scarcer and farther away each year. Famine was inevitable unless things changed. Also, the longer hunts took young students from the schools. A missionary farm seemed to be a solution and William Requa and Rev. Chapman from Union were chosen to lead the effort.

The mission farm started with enthusiasm but it was initially poorly equipped. By the time it started, some of the Indian families were already in the grip of the feared famine due to poor hunting. But a group of the Osage did take to the labors of agriculture and the plot produced well. This encouraged other members of the tribe to join the mission. However a severe flood in 1826 dampened enthusiasm and worse was to come for the first location. A treaty in 1828 placed Hopefield within the Cherokee Nation and they were not willing to allow the mission to continue. This initiated Hopefield #2 (below).

Mission Neosho, 1824 – 1829.

From a historical standpoint Mission Neosho is important for Kansas and Neosho County. It was the first school in present day Kansas and the first Kansas mission. Its story also exemplifies Louis Burns’ opening quote. The mission was started in September of 1824 by Rev. Benton Pixley, previously of Harmony Mission. It was located on the west bank of the Neosho River not far from present Shaw, Neosho County, Kansas. With all things considered, it had a fairly long life considering Rev. Pixley’s tendency to agitate. While many of Pixley’s opinions and actions were probably correct, his manner of expressing himself raised the fur on many necks. To borrow from Burns again:

“There were only five groups of people on the Osage frontier between 1820 and 1840. These were (1) Indians; (2) government employees, such as Agents, millers, and blacksmiths; (3) traders; (4) intruder settlers; and (5) missionaries. Pixley managed to antagonize all these groups except the missionaries. However … some Jesuit letters had more than a few harsh words about him. …”

Pixley was Presbyterian and more precisely a product of the New England puritanical religious beliefs. He held a hard distinction between right and wrong and there was no room for compromise. His demeanor caused an avalanche of letters to the government Board of Commissioners which led to his removal in early 1829. Perhaps more important, the Neosho Mission case might have weighed heavily on the Commissioner’s decision to suspend the Protestant Missions in 1837.

From a historical standpoint Mission Neosho is important for Kansas and Neosho County. It was the first school in present day Kansas and the first Kansas mission. Its story also exemplifies Louis Burns’ opening quote. The mission was started in September of 1824 by Rev. Benton Pixley, previously of Harmony Mission. It was located on the west bank of the Neosho River not far from present Shaw, Neosho County, Kansas. With all things considered, it had a fairly long life considering Rev. Pixley’s tendency to agitate. While many of Pixley’s opinions and actions were probably correct, his manner of expressing himself raised the fur on many necks. To borrow from Burns again:

“There were only five groups of people on the Osage frontier between 1820 and 1840. These were (1) Indians; (2) government employees, such as Agents, millers, and blacksmiths; (3) traders; (4) intruder settlers; and (5) missionaries. Pixley managed to antagonize all these groups except the missionaries. However … some Jesuit letters had more than a few harsh words about him. …”

Pixley was Presbyterian and more precisely a product of the New England puritanical religious beliefs. He held a hard distinction between right and wrong and there was no room for compromise. His demeanor caused an avalanche of letters to the government Board of Commissioners which led to his removal in early 1829. Perhaps more important, the Neosho Mission case might have weighed heavily on the Commissioner’s decision to suspend the Protestant Missions in 1837.

Boudinot Mission, 1830 – 1837.

Boudinot Mission was a re-invention of the ill-fated Mission Neosho, but about ten miles southeast. Boudinot was located near the juncture of Four-Mile Creek with the Neosho; or about 2-1/2 miles west-northwest of present St. Paul. It was also close to Chief White Hair’s main village.

The mission was started by Rev. Nathaniel Dodge of Harmony Mission after he and others saw that the Osages from Harmony were congregating in the lower reaches of the now-Kansas Neosho. This mission was operated primarily by Rev. Dodge and his family with the periodic help of other missionaries.

Compared to the other Protestant missions, little is known of Boudinot. In reading some of the letters copied in Graves’ “First Protestant Osage Missions”, the mission seems to have had some success with conversions; and even with convincing the local Indians to take up agriculture. There is also discussion of agitation and warfare in the area. Fur traders, who were unhappy because the Osages were being encouraged to farm, not hunt, might have stirred the pot too. In about 1835 Rev. Dodge abandoned the station and William Requa tried to keep it going for a while. Requa’s service at Boudinot was especially discouraging because he had to close the mission in 1836; then he returned to Missouri for a while.

Boudinot Mission was a re-invention of the ill-fated Mission Neosho, but about ten miles southeast. Boudinot was located near the juncture of Four-Mile Creek with the Neosho; or about 2-1/2 miles west-northwest of present St. Paul. It was also close to Chief White Hair’s main village.

The mission was started by Rev. Nathaniel Dodge of Harmony Mission after he and others saw that the Osages from Harmony were congregating in the lower reaches of the now-Kansas Neosho. This mission was operated primarily by Rev. Dodge and his family with the periodic help of other missionaries.

Compared to the other Protestant missions, little is known of Boudinot. In reading some of the letters copied in Graves’ “First Protestant Osage Missions”, the mission seems to have had some success with conversions; and even with convincing the local Indians to take up agriculture. There is also discussion of agitation and warfare in the area. Fur traders, who were unhappy because the Osages were being encouraged to farm, not hunt, might have stirred the pot too. In about 1835 Rev. Dodge abandoned the station and William Requa tried to keep it going for a while. Requa’s service at Boudinot was especially discouraging because he had to close the mission in 1836; then he returned to Missouri for a while.

Hopefield Mission #2, 1830 – 1835.

As noted, the Treaty of 1828 placed the Hopefield station inside of a new Cherokee reserve. While the Cherokees had a fairly congenial relationship with the missionaries, they would not allow continuance of the Hopefield Mission on the reserve. In 1830 William Requa and about fifteen families moved about twenty miles north to a new station home. On May 24, 1830, Requa wrote:

“The location of this station is on the same side of the Grand river with Union, about twenty-five miles north of it. The land is good, and for an Indian settlement, perhaps a better place could not have been selected ….”

One down-side of the new location was it was more remote and nearly separated from the Union Mission. While not autonomous by intent, it practically became a separate entity. Even so, the station enjoyed some success with both evangelization and education. The farms became productive and were able to provide the mission families with food and seed. But a series of tragic events led Hopefield #2 to its end.

On June 5th of 1833 William Requa’s wife, Susan, died after a long illness. It was written the Osages mourned her death as they would one of their own. The summer of 1834 brought a common malady of the scorching frontier summers—Cholera. The Missionary Herald of January 1836 recalled that 300 to 400 Osages died that summer, including about one-fourth of those at Hopefield. On August 17, 1834, Cholera also took the life a missionary, Rev. Montgomery. Compounding problems, William Requa was called to Boston to oversee publication of an Osage language elementary book that was prepared by Rev. Montgomery and himself. The absence of their leader took its toll on the mission. Hopefield #2 began a decline that led to its closing in April of 1835.

As noted, the Treaty of 1828 placed the Hopefield station inside of a new Cherokee reserve. While the Cherokees had a fairly congenial relationship with the missionaries, they would not allow continuance of the Hopefield Mission on the reserve. In 1830 William Requa and about fifteen families moved about twenty miles north to a new station home. On May 24, 1830, Requa wrote:

“The location of this station is on the same side of the Grand river with Union, about twenty-five miles north of it. The land is good, and for an Indian settlement, perhaps a better place could not have been selected ….”

One down-side of the new location was it was more remote and nearly separated from the Union Mission. While not autonomous by intent, it practically became a separate entity. Even so, the station enjoyed some success with both evangelization and education. The farms became productive and were able to provide the mission families with food and seed. But a series of tragic events led Hopefield #2 to its end.

On June 5th of 1833 William Requa’s wife, Susan, died after a long illness. It was written the Osages mourned her death as they would one of their own. The summer of 1834 brought a common malady of the scorching frontier summers—Cholera. The Missionary Herald of January 1836 recalled that 300 to 400 Osages died that summer, including about one-fourth of those at Hopefield. On August 17, 1834, Cholera also took the life a missionary, Rev. Montgomery. Compounding problems, William Requa was called to Boston to oversee publication of an Osage language elementary book that was prepared by Rev. Montgomery and himself. The absence of their leader took its toll on the mission. Hopefield #2 began a decline that led to its closing in April of 1835.

Hopefield Mission #3, 1837.

William Requa was undoubtedly discouraged with sixteen years of effort and progress well below his expectations. His short stay at Boudinot, and its closing, did not help. But after a short retreat to Missouri he decided to give the Neosho region another try. All that is known of the location of Hopefield #3 is it was on La Bette (Labette) Creek within nine miles of its junction with the Neosho. Buildings and staffing were arranged and he hoped to lead a colony of fifty families. But he moved into chaos. Before he arrived tribal hostilities broke out around the mission, cattle belonging to the mission were killed and some of the workers were assaulted by an opposing faction of the tribe. The mission never got started and this ended the Protestant efforts with the Osages.

William Requa was undoubtedly discouraged with sixteen years of effort and progress well below his expectations. His short stay at Boudinot, and its closing, did not help. But after a short retreat to Missouri he decided to give the Neosho region another try. All that is known of the location of Hopefield #3 is it was on La Bette (Labette) Creek within nine miles of its junction with the Neosho. Buildings and staffing were arranged and he hoped to lead a colony of fifty families. But he moved into chaos. Before he arrived tribal hostilities broke out around the mission, cattle belonging to the mission were killed and some of the workers were assaulted by an opposing faction of the tribe. The mission never got started and this ended the Protestant efforts with the Osages.

Time for a Change?

The Protestant efforts described above were well-organized and funded. By contrast the Jesuits were dealing with resource restrictions during the same period. Their missionary work was more sporadic and localized in Missouri and southeast Kansas. On some occasions the Catholics were welcomed at Harmony but generally they worked on their own. But the Jesuits relationship with the French and the Osages came to fruition a few years after the Protestants moved out. In May of 1844 nine chiefs of the Osage tribe submitted a petition to T. Harley Crawford, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. In it they stated:

“Hear what we have to say on this subject: We do not wish any more such missionaries as we have had during several years; for they never did us any good. Send them to the white; perhaps they may succeed better with them. If the Great Father desires that we have missionaries, you will tell him to send us Black-gowns, who will teach us to pray to the Great Spirit in the French manner.”

This petition was a link in a chain of events that led to the Catholic Mission in Neosho County.

The Protestant efforts described above were well-organized and funded. By contrast the Jesuits were dealing with resource restrictions during the same period. Their missionary work was more sporadic and localized in Missouri and southeast Kansas. On some occasions the Catholics were welcomed at Harmony but generally they worked on their own. But the Jesuits relationship with the French and the Osages came to fruition a few years after the Protestants moved out. In May of 1844 nine chiefs of the Osage tribe submitted a petition to T. Harley Crawford, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. In it they stated:

“Hear what we have to say on this subject: We do not wish any more such missionaries as we have had during several years; for they never did us any good. Send them to the white; perhaps they may succeed better with them. If the Great Father desires that we have missionaries, you will tell him to send us Black-gowns, who will teach us to pray to the Great Spirit in the French manner.”

This petition was a link in a chain of events that led to the Catholic Mission in Neosho County.

Go to: 5. The Catholic Osage Mission - or - Story.

Some Reference Information:

*Note: I relied heavily on Graves' "The First Protestant Osage Missions" for this section. It is a pretty detailed information source and I suspect it is unique in value for this subject. Unfortunately, it is out of print and the prospects for reprinting are slim. Preserving this book through OCR scanning and replicating would be a great project for someone with good scanning and word processing skills.

- The First Protestant Osage Missions 1820-1837, W.W. Graves, 1949*

- History of Neosho County Volumes I & II, W.W. Graves, 1951

- Beacon on the Plains, Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald, 1939

- Osage Indian Bands and Clans, Louis F. Burns, 1984

- A History of the Osage People, Louis F Burns, 1989

- Here is an article from the Kansas State Historical Society about Mission Neosho. It doesn't focus as much on the difficulties between Reverend Pixley and others in this area, but it does address some of the issues: https://www.kshs.org/p/mission-neosho-the-first-kansas-mission/12650

- Drawing of Harmony Mission painted by Mrs. Lucille Stevener from the memory of J.R.Barrow who lived at Harmony when the building was standing. Web source for the mission information and drawing: http://www.batescounty.net/history.php

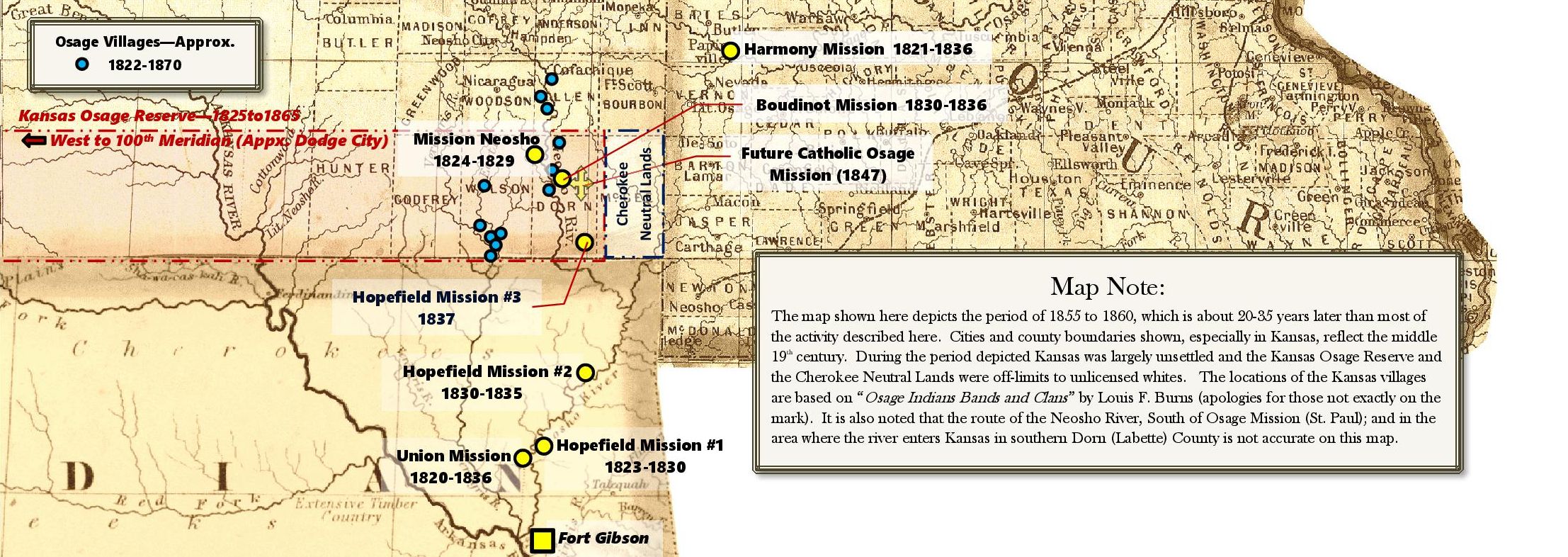

- The background of the map of village and mission locations was pulled together from several internet map sources and edited by R. Brogan. The same composite background is used to illustrate chapters 2, 3 and 4.

- Rootsweb – St. Clair County Missouri Churches http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~mostclai/Churches/ChurchesHarmonyMission.htm

*Note: I relied heavily on Graves' "The First Protestant Osage Missions" for this section. It is a pretty detailed information source and I suspect it is unique in value for this subject. Unfortunately, it is out of print and the prospects for reprinting are slim. Preserving this book through OCR scanning and replicating would be a great project for someone with good scanning and word processing skills.