9. The Osages Leave Their Kansas Reserve.

“The war deprived the Osages of all their labor and prospects. The youth of our school above the age of fifteen joined the Union army; 500 Osages had gone south; and of the remaining 3000, four companies, also joined the army. New trials were now upon us. Major Whitney, a special agent, had brot provisions for the destitute Osages, while John Mathews, my old friend whose five children I had raised in school, raised an alarm, entreating the Indians to regard the provisions as poisonous. This occurrence alienated me from my old friend Mathews and I was obliged to spend eight months at St. Mary’s in Pottawatomie County. On my return to the Osage Mission in March 1862, the Osages were much divided. Frequent intercourse with their southern relatives increased our dangers. ... The Osages during these hard times, visited me by day and by night.”

Excerpt from a speech made by Father John Schoenmakers, September 24, 1870 (Note at bottom of page.)

“The war deprived the Osages of all their labor and prospects. The youth of our school above the age of fifteen joined the Union army; 500 Osages had gone south; and of the remaining 3000, four companies, also joined the army. New trials were now upon us. Major Whitney, a special agent, had brot provisions for the destitute Osages, while John Mathews, my old friend whose five children I had raised in school, raised an alarm, entreating the Indians to regard the provisions as poisonous. This occurrence alienated me from my old friend Mathews and I was obliged to spend eight months at St. Mary’s in Pottawatomie County. On my return to the Osage Mission in March 1862, the Osages were much divided. Frequent intercourse with their southern relatives increased our dangers. ... The Osages during these hard times, visited me by day and by night.”

Excerpt from a speech made by Father John Schoenmakers, September 24, 1870 (Note at bottom of page.)

By 1865 the Four Horsemen had ravaged the Osage people. In addition to war, famine and pestilence; the white man’s civilization had more trials waiting. The Osages knew they would have to leave Kansas to accommodate the white settlers; and the government was eager to get on with their removal. There was mounting pressure to open the prairie to white settlers; and the end of the war produced a large number of recently discharged soldiers who were eager to stake claims. As a series of treaty negotiations drug out, settlers began to intrude on Osage land which increased tensions. One of the Government’s fears was increased violence, or a war between whites and Osage, that could spread to other tribes.

The Osage were an intelligent, perceptive people. They knew their avenues for departure included war with the white man or negotiation. Their chiefs knew, nearly 100 years earlier, they could not win an all-out war with the white armies and their killing machines. The tribal population was much smaller and fragile now; and the recent war reinforced their need to talk, not fight. What was left was negotiation. The Osages had acquired some education at the mission schools and had a wise advisor in Father Schoenmakers. But both the Osages and the settlers had ruthless adversaries in the railroad company robber-barons. Greedy executives were grabbing large parcels of newly-available land under the pretext of right-of-ways for the narrow iron transportation ribbons they would build.

The Way Out.

As the war wound down the Osage began to return to their former camping grounds only to find it littered with cabins and dugouts of white squatters brought there by the Homestead Act of 1862. In its most simple terms the Act allowed any adult, who had never taken up arms against the U.S. Government to apply for a 160 acre claim. Land was available west of Missouri and there were many adult males being discharged from Union army duty.

Between 1863 and the 1870 a chain of events led the Osage from southern Kansas into Oklahoma. The links of the chain were a series of treaties that are convoluted, complicated and beyond the scope of this page. The references include some details of these actions. The facts and the effect on the Osages are presented below:

1863 Government-Indian Council at LeRoy, Kansas:

The government’s opening position for this treaty was that the Osages give up their Kansas reservation. The head Chief, Little White Hair, promised to consider the offer in council but he could not reach consensus. Father Schoenmakers had been asked to participate in the discussions. He suggested the Osage only sell part of their reservation opening some land for settlement. All agreed to this. Since the land to be ceded was on the east end of the reserve, the Mission would be outside of their reservation. Therefore, the Osage stipulated that a section of land, including the mission buildings, be given to Father Schoenmakers free; and he be given the option of buying two more sections at the usual Government price of $1.25 an acre. The Indian Commissioner objected because that term seemed too generous; but then accepted what he could not change. The treaty was signed on August 29, 1863 and was promptly pigeonholed by the government.

The Osage were an intelligent, perceptive people. They knew their avenues for departure included war with the white man or negotiation. Their chiefs knew, nearly 100 years earlier, they could not win an all-out war with the white armies and their killing machines. The tribal population was much smaller and fragile now; and the recent war reinforced their need to talk, not fight. What was left was negotiation. The Osages had acquired some education at the mission schools and had a wise advisor in Father Schoenmakers. But both the Osages and the settlers had ruthless adversaries in the railroad company robber-barons. Greedy executives were grabbing large parcels of newly-available land under the pretext of right-of-ways for the narrow iron transportation ribbons they would build.

The Way Out.

As the war wound down the Osage began to return to their former camping grounds only to find it littered with cabins and dugouts of white squatters brought there by the Homestead Act of 1862. In its most simple terms the Act allowed any adult, who had never taken up arms against the U.S. Government to apply for a 160 acre claim. Land was available west of Missouri and there were many adult males being discharged from Union army duty.

Between 1863 and the 1870 a chain of events led the Osage from southern Kansas into Oklahoma. The links of the chain were a series of treaties that are convoluted, complicated and beyond the scope of this page. The references include some details of these actions. The facts and the effect on the Osages are presented below:

1863 Government-Indian Council at LeRoy, Kansas:

The government’s opening position for this treaty was that the Osages give up their Kansas reservation. The head Chief, Little White Hair, promised to consider the offer in council but he could not reach consensus. Father Schoenmakers had been asked to participate in the discussions. He suggested the Osage only sell part of their reservation opening some land for settlement. All agreed to this. Since the land to be ceded was on the east end of the reserve, the Mission would be outside of their reservation. Therefore, the Osage stipulated that a section of land, including the mission buildings, be given to Father Schoenmakers free; and he be given the option of buying two more sections at the usual Government price of $1.25 an acre. The Indian Commissioner objected because that term seemed too generous; but then accepted what he could not change. The treaty was signed on August 29, 1863 and was promptly pigeonholed by the government.

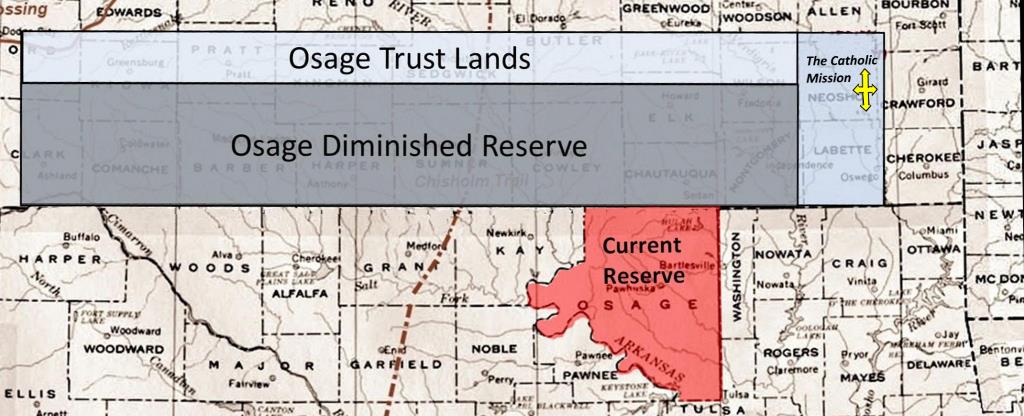

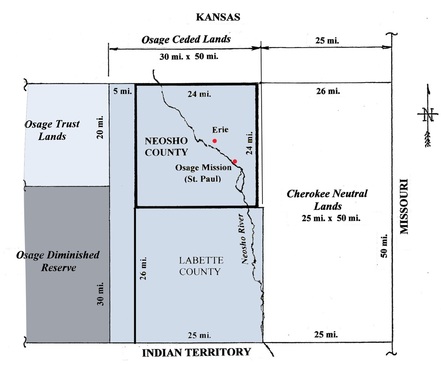

Detail of the reduction of Osage Lands at the east end of the Kansas reserve under terms of the Canville Treaty (Shaded in light blue below).

Detail of the reduction of Osage Lands at the east end of the Kansas reserve under terms of the Canville Treaty (Shaded in light blue below).

The Canville Treaty of 1865:

In early 1865 the LeRoy treaty resurfaced and President Lincoln struck out the grant to Father Schoenmakers. When the treaty was returned to the Osages they refused it. After Lincoln’s assassination in April of 1865, President Johnson sent a new commissioner to meet with the Osages. They met in council at the Canville Trading Post near present Shaw, Kansas and found the Indians still firm on granting the land to Father Schoenmakers. The commissioner reluctantly accepted the grant provision and the Osage signed what is called the Canville Treaty on September 29, 1865. The land-cession terms of this treaty included two parcels of land:

1. They ceded 960,000 acres in a strip 50 miles long (north-south) x 30 miles wide (east-west). This parcel extended from the eastern edge of the reserve to a point near the intersection of the Verdigris River with the southern border of Kansas (about five miles west of the Neosho - Labette County lines). In effect, it removed the counties of Neosho and Labette plus a small strip of Montgomery and Wilson Counties. The Osage were paid $300,000 for this land which was held in the U.S. treasury to pay five per cent interest for tribal needs.

2. In addition, they ceded a strip twenty miles wide across the entire northern length of the remaining reserve. This land comprising 2,944,000 acres was to be held in trust and sold at $1.25 an acre. Proceeds were to be spent on agricultural equipment, building and houses and the employment of a physicians and mechanics for service to the tribe.

In early 1865 the LeRoy treaty resurfaced and President Lincoln struck out the grant to Father Schoenmakers. When the treaty was returned to the Osages they refused it. After Lincoln’s assassination in April of 1865, President Johnson sent a new commissioner to meet with the Osages. They met in council at the Canville Trading Post near present Shaw, Kansas and found the Indians still firm on granting the land to Father Schoenmakers. The commissioner reluctantly accepted the grant provision and the Osage signed what is called the Canville Treaty on September 29, 1865. The land-cession terms of this treaty included two parcels of land:

1. They ceded 960,000 acres in a strip 50 miles long (north-south) x 30 miles wide (east-west). This parcel extended from the eastern edge of the reserve to a point near the intersection of the Verdigris River with the southern border of Kansas (about five miles west of the Neosho - Labette County lines). In effect, it removed the counties of Neosho and Labette plus a small strip of Montgomery and Wilson Counties. The Osage were paid $300,000 for this land which was held in the U.S. treasury to pay five per cent interest for tribal needs.

2. In addition, they ceded a strip twenty miles wide across the entire northern length of the remaining reserve. This land comprising 2,944,000 acres was to be held in trust and sold at $1.25 an acre. Proceeds were to be spent on agricultural equipment, building and houses and the employment of a physicians and mechanics for service to the tribe.

Ratification of the Canville Treaty did not end the Osages problems. As they moved west into the diminished reserve they were farther from the Mission; and they were still swarmed with intruders. Continued tension between the tribe and squatters led the government to requesting the Osage to sell all remaining land and move to a new tract in Indian Territory. The resulting negotiations were written into the infamous Sturgis or Drum Creek Treaty.

Sturgis (Drum Creek) Treaty of 1868:

The Sturgis Treaty laid open the unscrupulous tactics the railroad barons used to acquire land. The treaty council was held on a hill overlooking Drum Creek, Montgomery County, about three miles southeast of present Independence. The council was called by a commissioner named Colonel Taylor who invited Father Schoenmakers to be present. But as negotiations opened, Taylor turned control over to William Sturgis who was president of the Leavenworth, Lawrence, and Galveston Railroad. On the opposing side were representatives of the white settlers. Between the two sides was Father Schoenmakers in his role as protector of the Osage.

Sturgis immediately played the hand of a scoundrel by trying to bribe the priest with a section of land if he would influence the Indians in the railroad’s favor. But when the Indians came to him he told them to deal only with the Government and to insist that their land was to be sold for the benefit of the white settlers and not a corporation. When the Indians presented this position to the commissioner he urged them to reconsider. It was then that, for some reason, Father Schoenmakers withdrew from the meetings. He might have been needed at the Mission. But more likely he was concerned his presence would compromise the tribe. In his absence a report was received that an Osage had killed a white man near Winfield and the Commissioner used the event to browbeat the Indians into signing the treaty in the favor of the railroad. When Father Schoenmakers learned of the ruse, he was angered and urged the Osages to fight for defeat of the treaty in the Senate; and he assembled a team of leading citizens for support. When the citizens and state legislature realized the railroads were on the verge of controlling some 8,000,000 acres of prime farm and grazing land, the treaty was defeated. Had Sturgis been successful, the Osages would have sold their land to the unscrupulous railroad company for about 19 cents per acre.

At the end, the Railroaders were legally cut out of future treaty negotiations. The Drum Creek Treaty was re-tooled to provide the Osage with $1.25 per acre for their lands, to be paid by the settlers. In this form the treaty was ratified the following year. In July of 1870 Congress passed additional legislation mandating removal of the Osage from Kansas. During a final council at Drum Creek the Osages reluctantly agreed to leave, but added terms of their own. Where the treaty proposed the funds from sale of their land be held in interest bearing account; the Indians demanded that the government assist them in purchasing land in Indian Territory. Also, the purchased land would be owned by the tribe in common, not in severalty. The Cherokees were willing to sell a large tract in the north-central part of Indian Territory. After some confusion and renegotiating the new reserve consisted of 1,470,599 acres.

At the end of the 1870-1871 autumn hunt the Osage drifted into the eastern section of the new reserve. The new Osage reserve became Osage County which is the largest county in Oklahoma. It has been said they chose the Osage Hills area because it was so rocky and hilly that no white man would want it. It was not particularly good for farming, the labor they had resisted for years. But the tall blue-stem grass was well suited to ranching and their love for animals. Also, the decision to specify that the land be held in common became beneficial to all. The surface of the land could be improved and used as needed by the occupants. But the mineral rights beneath the soil were held in common. When the reality of the immense oil and gas reserves beneath Osage County became known, the wealth was distributed communally. At one time in the early 1900’s the Osage were among the richest people, per-capita, on earth. Also, much of the money we now leave in Osage casinos is distributed to the nation. What goes around eventually comes around.

Sturgis (Drum Creek) Treaty of 1868:

The Sturgis Treaty laid open the unscrupulous tactics the railroad barons used to acquire land. The treaty council was held on a hill overlooking Drum Creek, Montgomery County, about three miles southeast of present Independence. The council was called by a commissioner named Colonel Taylor who invited Father Schoenmakers to be present. But as negotiations opened, Taylor turned control over to William Sturgis who was president of the Leavenworth, Lawrence, and Galveston Railroad. On the opposing side were representatives of the white settlers. Between the two sides was Father Schoenmakers in his role as protector of the Osage.

Sturgis immediately played the hand of a scoundrel by trying to bribe the priest with a section of land if he would influence the Indians in the railroad’s favor. But when the Indians came to him he told them to deal only with the Government and to insist that their land was to be sold for the benefit of the white settlers and not a corporation. When the Indians presented this position to the commissioner he urged them to reconsider. It was then that, for some reason, Father Schoenmakers withdrew from the meetings. He might have been needed at the Mission. But more likely he was concerned his presence would compromise the tribe. In his absence a report was received that an Osage had killed a white man near Winfield and the Commissioner used the event to browbeat the Indians into signing the treaty in the favor of the railroad. When Father Schoenmakers learned of the ruse, he was angered and urged the Osages to fight for defeat of the treaty in the Senate; and he assembled a team of leading citizens for support. When the citizens and state legislature realized the railroads were on the verge of controlling some 8,000,000 acres of prime farm and grazing land, the treaty was defeated. Had Sturgis been successful, the Osages would have sold their land to the unscrupulous railroad company for about 19 cents per acre.

At the end, the Railroaders were legally cut out of future treaty negotiations. The Drum Creek Treaty was re-tooled to provide the Osage with $1.25 per acre for their lands, to be paid by the settlers. In this form the treaty was ratified the following year. In July of 1870 Congress passed additional legislation mandating removal of the Osage from Kansas. During a final council at Drum Creek the Osages reluctantly agreed to leave, but added terms of their own. Where the treaty proposed the funds from sale of their land be held in interest bearing account; the Indians demanded that the government assist them in purchasing land in Indian Territory. Also, the purchased land would be owned by the tribe in common, not in severalty. The Cherokees were willing to sell a large tract in the north-central part of Indian Territory. After some confusion and renegotiating the new reserve consisted of 1,470,599 acres.

At the end of the 1870-1871 autumn hunt the Osage drifted into the eastern section of the new reserve. The new Osage reserve became Osage County which is the largest county in Oklahoma. It has been said they chose the Osage Hills area because it was so rocky and hilly that no white man would want it. It was not particularly good for farming, the labor they had resisted for years. But the tall blue-stem grass was well suited to ranching and their love for animals. Also, the decision to specify that the land be held in common became beneficial to all. The surface of the land could be improved and used as needed by the occupants. But the mineral rights beneath the soil were held in common. When the reality of the immense oil and gas reserves beneath Osage County became known, the wealth was distributed communally. At one time in the early 1900’s the Osage were among the richest people, per-capita, on earth. Also, much of the money we now leave in Osage casinos is distributed to the nation. What goes around eventually comes around.

Note:

Father Schoenmakers’ role as adviser and confidant to the Osage people is exemplified in his role during the final treaty negotiations. After he initially gained their trust, the Osage called on him often for legal as well as spiritual advice. But it was his intervention during the Drum Creek negotiations that solidified his everlasting role as “Apostle to the Osages.” Had the Drum Creek Treaty have been ratified as presented by the railroad interests the government would have chosen the new land for them, and they would not have held title. Instead, they purchased their own land in Indian Territory and owned the mineral rights to the vast oil and gas fields beneath them.

Father Schoenmakers’ participation in the treaty negotiations also benefited the white settlers and prevented a legal miscarriage that would have had long-reaching effects. Had the rail companies seized large parcels of land, they would have demanded prohibitive prices from the settlers. They would have also acquired nearly 450,000 acres of land that had been set aside by the Homestead Act for school funding.

His Speech: The opening quote is from a speech Father Schoenmakers gave at the opening of the Osage Mission Grist Mill in September of 1870. A reporter from the Leavenworth Commercial recorded it. I believe it says a lot about Father John's past and the way he thought about things. It is linked here.

Father Schoenmakers’ role as adviser and confidant to the Osage people is exemplified in his role during the final treaty negotiations. After he initially gained their trust, the Osage called on him often for legal as well as spiritual advice. But it was his intervention during the Drum Creek negotiations that solidified his everlasting role as “Apostle to the Osages.” Had the Drum Creek Treaty have been ratified as presented by the railroad interests the government would have chosen the new land for them, and they would not have held title. Instead, they purchased their own land in Indian Territory and owned the mineral rights to the vast oil and gas fields beneath them.

Father Schoenmakers’ participation in the treaty negotiations also benefited the white settlers and prevented a legal miscarriage that would have had long-reaching effects. Had the rail companies seized large parcels of land, they would have demanded prohibitive prices from the settlers. They would have also acquired nearly 450,000 acres of land that had been set aside by the Homestead Act for school funding.

His Speech: The opening quote is from a speech Father Schoenmakers gave at the opening of the Osage Mission Grist Mill in September of 1870. A reporter from the Leavenworth Commercial recorded it. I believe it says a lot about Father John's past and the way he thought about things. It is linked here.

Go to: 10. A Very Unique Community is Born - or - Story

Some Reference Information:

- A History of the Osage People, Louis F. Burns, 1989

- Beacon on the Plains, Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald, 1939

- Father John Schoenmakers S. J. – Apostle to the Osages, W.W. Graves, 1928

- Getting Sense, The Osages and Their Missionaries, James D. White, 1997

- The Osages – Children of the Middle Waters, John Joseph Mathews, 1961

- Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties – Treaty with the Osage, 1865; Oklahoma State University Digital Library. This link includes details of the treaty of 1865. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/vol2/treaties/osa0878.htm

- The top, banner map, and the one used in text, was cropped and edited from the composite map described in Part 7, The Missionary Trails. The small map showing the reduction of Osage Lands was hand-drawn for a museum display that has since been taken down.