8. A Dangerous Balance – The Civil War (1861 – 1865)

Perhaps the most remarkable part of the Mission’s Civil War story is that it survived and we are here today.

Perhaps the most remarkable part of the Mission’s Civil War story is that it survived and we are here today.

There is a story about a Union officer who used his sword to draw a line in the dust of the Mission courtyard—‘Everything north is Union and everything south is Confederate!’ True or not, this story illustrates the precarious existence of the Mission during the war.

The local war was a guerrilla conflict consisting of individual raids, burnings and murders. Organized troop movements did not enter Kansas until 1862; and even then much of the trouble came from bands of thugs and bandits who used the war as an excuse to rob and pillage. The only white people allowed to settle in the Osage reserve were missionaries and a few licensed traders and mechanics. Occupants were expected to choose a side and either choice was risky. Cabins and trading posts were routinely abandoned or burned.

The Mission was isolated and between forces. Fort Scott was 35 miles northeast; and Fort Blair (Baxter Springs) was not fully operational until 1863. Confederate sympathizer John Mathews operated a store/blacksmith shop 25 miles south near present-day Oswego. Mathews had migrated from Kentucky, then Missouri with the Osage, had two wives, and one of them was a mixed-blood Osage woman. His children attended school at Osage Mission. Mathews is recognized as one of the most notorious Confederate militia leaders in Southeast Kansas. To make matters more interesting, the Osage were viewed as a formidable military strength and their reserve stretching along much of the southern border of Kansas was strategic. Both Mathews and Fr. Schoenmakers had considerable influence with the tribe. A strong friendship between the two men was severely strained.

Tough Decisions, A Stressful Existence.

Fr. Schoenmakers had few options. The Mission was a government facility and he morally objected to slavery. Also he was responsible for several orphaned Osage children. Abandoning the Mission would amount to abandoning them. His only choice was to maintain tenuous neutrality.

The Mission was able to operate under constantly stressful conditions for about three years. The sisters frequently fed and dressed wounds for both Union and Confederate soldiers. Occasionally they served both sides during a single day—sometimes at the same time under a white flag. But there were events that nearly brought disaster:

The local war was a guerrilla conflict consisting of individual raids, burnings and murders. Organized troop movements did not enter Kansas until 1862; and even then much of the trouble came from bands of thugs and bandits who used the war as an excuse to rob and pillage. The only white people allowed to settle in the Osage reserve were missionaries and a few licensed traders and mechanics. Occupants were expected to choose a side and either choice was risky. Cabins and trading posts were routinely abandoned or burned.

The Mission was isolated and between forces. Fort Scott was 35 miles northeast; and Fort Blair (Baxter Springs) was not fully operational until 1863. Confederate sympathizer John Mathews operated a store/blacksmith shop 25 miles south near present-day Oswego. Mathews had migrated from Kentucky, then Missouri with the Osage, had two wives, and one of them was a mixed-blood Osage woman. His children attended school at Osage Mission. Mathews is recognized as one of the most notorious Confederate militia leaders in Southeast Kansas. To make matters more interesting, the Osage were viewed as a formidable military strength and their reserve stretching along much of the southern border of Kansas was strategic. Both Mathews and Fr. Schoenmakers had considerable influence with the tribe. A strong friendship between the two men was severely strained.

Tough Decisions, A Stressful Existence.

Fr. Schoenmakers had few options. The Mission was a government facility and he morally objected to slavery. Also he was responsible for several orphaned Osage children. Abandoning the Mission would amount to abandoning them. His only choice was to maintain tenuous neutrality.

The Mission was able to operate under constantly stressful conditions for about three years. The sisters frequently fed and dressed wounds for both Union and Confederate soldiers. Occasionally they served both sides during a single day—sometimes at the same time under a white flag. But there were events that nearly brought disaster:

Father Schoenmakers’ Exile (July 21, 1861-March 1862).

Maintaining neutrality was difficult especially while operating a United States government school. Making matters worse, the government Indian Agent, Andrew J. Dorn, was a southerner who was supporting the Confederacy and actively recruiting Osage for their war effort.

During the summer of 1861 Father Schoenmakers was called on to guide a couple of United States government officials to the Quapaw Agency southeast of the Mission. This event did not go well and resulted in a bushwhacker plan to kill Father Schoenmakers. According to some accounts John Mathews was at the center of this plot. But it is interesting to note that the Mission staff was unaware of the plot until the evening of July 21st when a messenger arrived at the Mission to warn Fathers Schoenmakers, Ponziglione and Van Goch. Some accounts say the messenger was one of Mathews’ sons; others say the message was sent by one of Mathew’s offspring. Upon receipt of the news the three priests discussed the situation and their options. Under advice of Fathers Ponziglione and Van Goch, Father Schoenmakers decided it would be best for the mission and himself if he left immediately. He mounted one of the Mission stable’s best horses and set out for Humboldt. As fortune, and perhaps prayer, would have it his departure was coincident with a three-day rain storm that flooded local streams preventing the attackers from reaching the Mission until the priest was long gone. After a brief stay in Humboldt Father Schoenmakers went to the Jesuit Potawatomi mission at St. Mary’s where he remained until the following March. During his absence Father Ponziglione assumed the superior’s duties; and the two following events occurred during his tenure.

Maintaining neutrality was difficult especially while operating a United States government school. Making matters worse, the government Indian Agent, Andrew J. Dorn, was a southerner who was supporting the Confederacy and actively recruiting Osage for their war effort.

During the summer of 1861 Father Schoenmakers was called on to guide a couple of United States government officials to the Quapaw Agency southeast of the Mission. This event did not go well and resulted in a bushwhacker plan to kill Father Schoenmakers. According to some accounts John Mathews was at the center of this plot. But it is interesting to note that the Mission staff was unaware of the plot until the evening of July 21st when a messenger arrived at the Mission to warn Fathers Schoenmakers, Ponziglione and Van Goch. Some accounts say the messenger was one of Mathews’ sons; others say the message was sent by one of Mathew’s offspring. Upon receipt of the news the three priests discussed the situation and their options. Under advice of Fathers Ponziglione and Van Goch, Father Schoenmakers decided it would be best for the mission and himself if he left immediately. He mounted one of the Mission stable’s best horses and set out for Humboldt. As fortune, and perhaps prayer, would have it his departure was coincident with a three-day rain storm that flooded local streams preventing the attackers from reaching the Mission until the priest was long gone. After a brief stay in Humboldt Father Schoenmakers went to the Jesuit Potawatomi mission at St. Mary’s where he remained until the following March. During his absence Father Ponziglione assumed the superior’s duties; and the two following events occurred during his tenure.

Pistol Leveled at Fr. Paul (August 1861).

A few weeks after Father Schoenmakers’ departure six armed men entered the Mission and surrounded Father Ponziglione. They demanded the surrender of a Confederate officer he was hiding. Fr. Ponziglione assured them that the Mission was a U.S. government school and not a hiding place for Confederates. The thugs then claimed to be Confederates and demanded the release of a Union soldier he was hiding. When the priest laughed at them over their lack of consistency, the leader drew and leveled his pistol at Fr. Ponziglione’s head. At that moment a group of half-breed Osage intervened and it took some insistence, on Father’s part, to prevent them from avenging his honor.

A few weeks after Father Schoenmakers’ departure six armed men entered the Mission and surrounded Father Ponziglione. They demanded the surrender of a Confederate officer he was hiding. Fr. Ponziglione assured them that the Mission was a U.S. government school and not a hiding place for Confederates. The thugs then claimed to be Confederates and demanded the release of a Union soldier he was hiding. When the priest laughed at them over their lack of consistency, the leader drew and leveled his pistol at Fr. Ponziglione’s head. At that moment a group of half-breed Osage intervened and it took some insistence, on Father’s part, to prevent them from avenging his honor.

Two Dangerous Events (October, 1861).

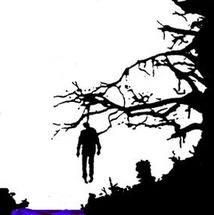

During October of 1861 two hundred Confederate soldiers entered the Mission yard. They were under the leadership of Colonel Stand Watie, a Cherokee half-breed, and two white men, Captains Livingston and John Mathews. The leaders assured Father Ponziglione they were there to do no harm. However, Fr. Paul wrote: “Though it was Sunday they did not come to attend Vespers.” After refreshing at the Mission well they camped at a crossing at Four Mile Creek, west of the Mission. The following morning, as though to mark their spot, they left the body of a poor white man hanging from a tree on the bank of the creek. From there they rode to Humboldt where they raided the town in retaliation for an earlier Union attack in western Missouri. General Lane and his Union forces were absent from the Humboldt, so the rebels were able to easily take the town and plunder it of valuables and several kegs of whiskey.

On their homeward route the whiskey had kicked in and several of the troops were in need of a drink of fresh water from the Mission well. Then, a group of the most heavily intoxicated threatened to enter the convent. Father Ponziglione intervened and was restrained by the soldiers. John Mathews was nearby and the priest appealed to Mathews not to let this atrocity occur at the school of his own children. Mathews stepped forward with clenched fists and snarled an order for the troops to “Clear out”. The men understood he was a formidable fighter and an exceptional shot and they took heed. Then Mathews assured the priest that he would move his troops several miles east, post a guard, and if anyone tried to return they would be shot. No further annoyance occurred but the Mission had come close to an un-reversible tragedy. (See note below).

Father Van Goch’s Encounter (December 1861).

Confederate soldiers were not the only ones to disrespect the neutrality of the missionary priests. On a December afternoon Father James Van Goch was riding alone toward Ft. Scott when he was stopped by a group of Union soldiers. With the exception of their leader, Captain Bell, the group was intoxicated. The priest was forced to dismount and kneel. He was about to be shot when Bell urged that he deserved a fair trial. The soldiers agreed. Father Van Goch was told to remount and the group rode to a camp. Bell ordered his men to take their horses to graze along a creek. With the men out of site, Captain Bell and the priest galloped away to the safety of the house where Fr. Van Goch planned to celebrate Mass the next morning, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception.

Confederate Officers Massacred on the Verdigris (May, 1863).

This event, which might have had a significant impact on the war, occurred on the Verdigris River between Caney and Independence. The description is rather long so I have presented it on a separate page.

During October of 1861 two hundred Confederate soldiers entered the Mission yard. They were under the leadership of Colonel Stand Watie, a Cherokee half-breed, and two white men, Captains Livingston and John Mathews. The leaders assured Father Ponziglione they were there to do no harm. However, Fr. Paul wrote: “Though it was Sunday they did not come to attend Vespers.” After refreshing at the Mission well they camped at a crossing at Four Mile Creek, west of the Mission. The following morning, as though to mark their spot, they left the body of a poor white man hanging from a tree on the bank of the creek. From there they rode to Humboldt where they raided the town in retaliation for an earlier Union attack in western Missouri. General Lane and his Union forces were absent from the Humboldt, so the rebels were able to easily take the town and plunder it of valuables and several kegs of whiskey.

On their homeward route the whiskey had kicked in and several of the troops were in need of a drink of fresh water from the Mission well. Then, a group of the most heavily intoxicated threatened to enter the convent. Father Ponziglione intervened and was restrained by the soldiers. John Mathews was nearby and the priest appealed to Mathews not to let this atrocity occur at the school of his own children. Mathews stepped forward with clenched fists and snarled an order for the troops to “Clear out”. The men understood he was a formidable fighter and an exceptional shot and they took heed. Then Mathews assured the priest that he would move his troops several miles east, post a guard, and if anyone tried to return they would be shot. No further annoyance occurred but the Mission had come close to an un-reversible tragedy. (See note below).

Father Van Goch’s Encounter (December 1861).

Confederate soldiers were not the only ones to disrespect the neutrality of the missionary priests. On a December afternoon Father James Van Goch was riding alone toward Ft. Scott when he was stopped by a group of Union soldiers. With the exception of their leader, Captain Bell, the group was intoxicated. The priest was forced to dismount and kneel. He was about to be shot when Bell urged that he deserved a fair trial. The soldiers agreed. Father Van Goch was told to remount and the group rode to a camp. Bell ordered his men to take their horses to graze along a creek. With the men out of site, Captain Bell and the priest galloped away to the safety of the house where Fr. Van Goch planned to celebrate Mass the next morning, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception.

Confederate Officers Massacred on the Verdigris (May, 1863).

This event, which might have had a significant impact on the war, occurred on the Verdigris River between Caney and Independence. The description is rather long so I have presented it on a separate page.

Mission Blacksmith Murdered (November, 1863).

A foiled bushwhacker raid during late 1863 brought both tragedy and security to the Mission. With winter approaching, blankets were a prized commodity for troops living mostly in camps. Word spread that the Mission had received a shipment of blankets from St. Louis. Thirty half-breed youths, aided by a group of bushwhackers, planned a raid on the Mission, including the convent. At about midnight, one of the half-breed scouts must have mistaken a shadow of a tree for the image of a soldier (There were no Union soldiers on the grounds). With a war-whoop he ran back to the group who mounted and galloped toward Flat Rock Creek. Near the creek they entered the cabin of a poor Mission blacksmith. There they vented frustration by shooting the innocent man in front of his wife and child—and then disappeared into the darkness. Father Schoenmakers was summoned and came immediately with medical supplies. But care and medicine were inadequate to treat a ghastly bullet wound near the heart. The blacksmith died within days.

When informed of the murder, the Commander at Fort Scott, Brigadier General Charles W. Blair sent a company of cavalry to establish a post near the Mission. The soldiers camped on the west bank of Flat Rock for a week while building a post in front of the mission buildings. It is believed this post was located south of the present church near the museum grounds.

Perhaps the best security came from the students and teachers. The missionaries reported occasions when destruction of the Mission seemed unavoidable. But when war-hardened guerrillas entered the church and observed the Indian children and sisters, with heads bowed in silent prayer, they were taken aback. They removed hats, quietly left the building, mounted horses and rode away.

A foiled bushwhacker raid during late 1863 brought both tragedy and security to the Mission. With winter approaching, blankets were a prized commodity for troops living mostly in camps. Word spread that the Mission had received a shipment of blankets from St. Louis. Thirty half-breed youths, aided by a group of bushwhackers, planned a raid on the Mission, including the convent. At about midnight, one of the half-breed scouts must have mistaken a shadow of a tree for the image of a soldier (There were no Union soldiers on the grounds). With a war-whoop he ran back to the group who mounted and galloped toward Flat Rock Creek. Near the creek they entered the cabin of a poor Mission blacksmith. There they vented frustration by shooting the innocent man in front of his wife and child—and then disappeared into the darkness. Father Schoenmakers was summoned and came immediately with medical supplies. But care and medicine were inadequate to treat a ghastly bullet wound near the heart. The blacksmith died within days.

When informed of the murder, the Commander at Fort Scott, Brigadier General Charles W. Blair sent a company of cavalry to establish a post near the Mission. The soldiers camped on the west bank of Flat Rock for a week while building a post in front of the mission buildings. It is believed this post was located south of the present church near the museum grounds.

Perhaps the best security came from the students and teachers. The missionaries reported occasions when destruction of the Mission seemed unavoidable. But when war-hardened guerrillas entered the church and observed the Indian children and sisters, with heads bowed in silent prayer, they were taken aback. They removed hats, quietly left the building, mounted horses and rode away.

A Note about John Mathews:

Shortly after the Humboldt raid and subsequent threat at the Mission yard John Mathews was tracked down by Union troops and killed near Chetopa. His death was later avenged by a more destructive raid on Humboldt. The question remains - did John Mathews organize the threat that led to Father Schoenmakers exile; or did he warn him? later writings of the priests, especially Fr. Ponziglione, seemed to favor him and credit him with saving the Mission. Fr. Ponziglione in particular considered Mathews to be a man of conviction who died with his beliefs. A man of lesser determination might have lived to see his children and grandchildren grow up.

One of John Mathews’ grandsons was noted Osage advocate, Council member, historian and author John Joseph Mathews (1894-1979). John Joseph’s comment in his book “The Osage, Children of the Middle Waters” is brief and to the point: “The breach between him (John Mathews) and Father Schoenmakers became a chasm, and he finally drove Father Schoenmakers, the loyalist, from the mission in June of 1861.”

Shortly after the Humboldt raid and subsequent threat at the Mission yard John Mathews was tracked down by Union troops and killed near Chetopa. His death was later avenged by a more destructive raid on Humboldt. The question remains - did John Mathews organize the threat that led to Father Schoenmakers exile; or did he warn him? later writings of the priests, especially Fr. Ponziglione, seemed to favor him and credit him with saving the Mission. Fr. Ponziglione in particular considered Mathews to be a man of conviction who died with his beliefs. A man of lesser determination might have lived to see his children and grandchildren grow up.

One of John Mathews’ grandsons was noted Osage advocate, Council member, historian and author John Joseph Mathews (1894-1979). John Joseph’s comment in his book “The Osage, Children of the Middle Waters” is brief and to the point: “The breach between him (John Mathews) and Father Schoenmakers became a chasm, and he finally drove Father Schoenmakers, the loyalist, from the mission in June of 1861.”

Go to: 9. The Osages Leave Their Kansas Reserve - or - Story - or -

8A. Confederate Officers Massacred on the Verdigris (May, 1863).

8A. Confederate Officers Massacred on the Verdigris (May, 1863).

Some Reference Information:

- Beacon on the Plains by Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald, PhD, St. Mary’s College, Leavenworth, KS (1939)

- Father John Schoenmakers S.J., Apostle to the Osages, W.W. Graves, St. Paul, KS (1928)

- Life and Letters of Fathers Ponziglione, Schoenmakers and Other Early Jesuits at Osage Mission, W.W. Graves, St. Paul, KS (1916)

- Life and Times of Mother Bridget, W.W. Graves, St. Paul, KS, (1938)

- The Osage, Children of the Middle Waters, John Joseph Mathews, 1961

- The top map was edited from an internet map source (unknown) by A Catholic Mission.

- To be truthful, all remaining art on the page was edited for presentations years ago and I cannot remember the sources. I believe the photo of John Mathews came from the Oswego Museum.