Chapter XI — Miss Lucille St. Pierre Came to the Neosho

This is a chapter from the memoirs of Jesuit missionary Father Paul Mary Ponziglione. The entire work includes fifty chapters and several appendices, more than 560 total pages. The memoir was written during the approximate time frame of 1896 through 1898 while Father Paul was assigned to St. Ignatius College, Chicago. He died on March 28, 1900. The memoir was titled "Interesting Memoirs Collected from Legend, Traditions and Historical Documents". The story below, while based on facts and real historical names, occurred in 1847, about four years before he arrived at Osage Mission. [1] It has been transcribed from a microfilm copy of his work. Illustrations added by us.

This is a chapter from the memoirs of Jesuit missionary Father Paul Mary Ponziglione. The entire work includes fifty chapters and several appendices, more than 560 total pages. The memoir was written during the approximate time frame of 1896 through 1898 while Father Paul was assigned to St. Ignatius College, Chicago. He died on March 28, 1900. The memoir was titled "Interesting Memoirs Collected from Legend, Traditions and Historical Documents". The story below, while based on facts and real historical names, occurred in 1847, about four years before he arrived at Osage Mission. [1] It has been transcribed from a microfilm copy of his work. Illustrations added by us.

Chapter XI

Miss Lucille St. Pierre came to the Neosho — Stays with Mr. Michael Giraud — gets lost — is found.

During the Winter of 1847 Miss Lucille St. Pierre, a respectable young lady of New Orleans was sent by her father to St. Louis on a special business. Mr. Anthony St. Pierre had, for several years, been acting agent for Mr. Benoit De Bonald, a French botanist, whose charge was to supply the Paris botanical gardens with a special collection of a complete North American flora. To succeed with facility in this undertaking, Mr. Benoit De Bonald had classified his flora according to the different States and Territories of the Union. These he had subdivided into special departments, appointing to the head of each persons residing in these places and well capable to conduct this gigantic work with success. Knowing that Anthony St. Pierre was in correspondence with several French merchants of St. Louis, who, long since, were dealing with Indians, especially in that part of the Indian Territory now in the State of Kansas, he appointed him to see to that section of country, and wished him to procure a correct flora of the Neosho and Verdigris valleys.

During the Winter of 1847 Miss Lucille St. Pierre, a respectable young lady of New Orleans was sent by her father to St. Louis on a special business. Mr. Anthony St. Pierre had, for several years, been acting agent for Mr. Benoit De Bonald, a French botanist, whose charge was to supply the Paris botanical gardens with a special collection of a complete North American flora. To succeed with facility in this undertaking, Mr. Benoit De Bonald had classified his flora according to the different States and Territories of the Union. These he had subdivided into special departments, appointing to the head of each persons residing in these places and well capable to conduct this gigantic work with success. Knowing that Anthony St. Pierre was in correspondence with several French merchants of St. Louis, who, long since, were dealing with Indians, especially in that part of the Indian Territory now in the State of Kansas, he appointed him to see to that section of country, and wished him to procure a correct flora of the Neosho and Verdigris valleys.

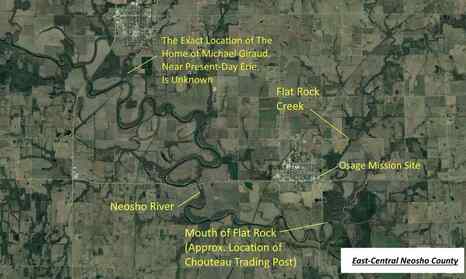

Events described here occurred along the banks of the Neosho River near present day St. Paul and Erie, Kansas. Click to enlarge.

Events described here occurred along the banks of the Neosho River near present day St. Paul and Erie, Kansas. Click to enlarge.

It was the 1st of February when Miss Lucille St. Pierre left New Orleans, and, after a rather tedious navigation of many days, at last landed at St. Louis, where she was most kindly received by the Chouteaus. Mr. Edward being daily expected from his trading post on the Neosho, the young lady was requested to delay her departure till after his coming. In fact, he was coming a few days after her arrival, and, having purchased a large supply of spring goods, by the 12th of March, left with Miss Lucille for Kansas City on Captain La Barge's Steamboat. The Missouri, not being as yet fairly opened, they ascended it very slow, and, meeting with no accident, reached Westport's landing about the end of the month. Here they became the guests of Mrs. Menard Chouteau, a most accomplished lady, known through the whole West for her hospitality.

Several days having been employed in getting ready to cross the 140 miles of desert prairie standing between Kansas City and the Neosho, Mr. Edward's outfit left, and, after two weeks journey, at last, on the 15th of April, reached the mouth of Flat-Rock, where Mr. Edward's residence was.

The unexpected appearance of Miss Lucille was quite a surprise to Mrs. Rosalia, the wife of Mr. Edward Chouteau. This lady was an Osage half-breed well educated. She received Lucille with great cordiality and wished her to make herself at home with her. But Lucille, knowing that her father's preference was that she should rather stay with Mr. Michael Giraud, [2] declined her kind invitation, and went to stop with the now mentioned gentleman, whose residence was some seven miles up the Neosho, west of the place where at present stands the city of Erie.

Mr. M. Giraud, having no children, looked on Lucille as a very valuable acquisition to his family and treated her with parental affection. The season of spring, being now beautifully developed, Lucille prepared herself for her work and, by the end of May, she had already begun her Neosho flora. She is out every day on the high prairies east of Giraud's home, looking for blossoms. Not being acquainted with the country, Mr. Giraud allows her as a companion and guide in her excursions a very interesting Indian child by the name of Angelica Mitceke, whom he was raising and loved and looked upon as if it had been his own. The gentle training Angelica had received from Mr. Giraud had so much tempered her wild character that no one could believe that there was one drop of Indian blood in her. As she spoke the French with a very correct accent, Lucille could not help but love her and she now began to consider her and love her as if she had been her natural sister.

Several days having been employed in getting ready to cross the 140 miles of desert prairie standing between Kansas City and the Neosho, Mr. Edward's outfit left, and, after two weeks journey, at last, on the 15th of April, reached the mouth of Flat-Rock, where Mr. Edward's residence was.

The unexpected appearance of Miss Lucille was quite a surprise to Mrs. Rosalia, the wife of Mr. Edward Chouteau. This lady was an Osage half-breed well educated. She received Lucille with great cordiality and wished her to make herself at home with her. But Lucille, knowing that her father's preference was that she should rather stay with Mr. Michael Giraud, [2] declined her kind invitation, and went to stop with the now mentioned gentleman, whose residence was some seven miles up the Neosho, west of the place where at present stands the city of Erie.

Mr. M. Giraud, having no children, looked on Lucille as a very valuable acquisition to his family and treated her with parental affection. The season of spring, being now beautifully developed, Lucille prepared herself for her work and, by the end of May, she had already begun her Neosho flora. She is out every day on the high prairies east of Giraud's home, looking for blossoms. Not being acquainted with the country, Mr. Giraud allows her as a companion and guide in her excursions a very interesting Indian child by the name of Angelica Mitceke, whom he was raising and loved and looked upon as if it had been his own. The gentle training Angelica had received from Mr. Giraud had so much tempered her wild character that no one could believe that there was one drop of Indian blood in her. As she spoke the French with a very correct accent, Lucille could not help but love her and she now began to consider her and love her as if she had been her natural sister.

Angelica knew where there were flowers that would please Lucille. [3]

Angelica knew where there were flowers that would please Lucille. [3]

Close to Mr. Giraud's home the Neosho is meandering through charming timber land and this was a favorite place of resort for our florists during the hot hours of the day, for here the air was cooled by large shade trees and the ground was carpeted by a variety of rare flowers. On the 27th of June Lucille has just come with Angelica to this nice spot, when some young squaws, being on their way to their wigwams, happened to be passing by. Well knowing that the French girl was collecting flowers, they presented her with a beautiful bouquet. Lucille was very much pleased at their kindness, and wished to know where they gathered such sweet blossoms. To this they simply replied: "On the hill far west." Once they had gone, she asked Angelica whether she knew the place where these flowers were growing. "Oh, yes," was her answer "way yonder on that high bluff" pointing at it with her finger. "The boys" she added, "call these flowers Ckijhujhi-glajca, which means Love-flower because when they wish to make us a nice present, they will bring us a bunch of them."

This was enough to excite Lucille's curiosity and she makes up her mind to go to find the place and make a good collection before the blasting heat of July would set in. To this effect, she told Angelica, that she intended to go to that hill on the next day, "and you, my child," she said, "do not forget to take a lunch in your basket, that we may not need to come home for dinner." However, noticing that they would have to cross the river in a small canoe, she seems to be perplexed in her mind, and, looking at Angelica with some anxiety she said: "But, my dear child, I see that we will have to cross the diver, and who is going to paddle the skiff for us?" To this Angelica replies "I will; I am well used to it. Whenever Uncle Giraud wants to go to the other side to gather wild onions and strawberries, I always paddle the canoe for him." This answer did fully satisfy Lucille and nothing more was said about it.

The sun had risen as bright as ever and the sky looked as pure as a nice crystal, when, at the balmy breeze of the 28th of June, our florists were out for the West. Hardly had they reached the bank of the river, when, in the twinkling of an eye, Angelica leaped in the canoe and coasting along with masterly hand she invited her companion to come on board. Lucille steps in very cautiously and seats herself at the helm; meanwhile that Angelica softly but steadily begins to row. The water being very calm in but a few minutes they land on the opposite bank.

Here, leaving the lunch basket in the canoe, both spring on terra firma, and, twisting the line of their little boat to a sapling, both start at work. No body living on that side of the river, the ground is literally all dotted with quite a variety of flowers. On they are going at random, picking up only the choicest, and, at every steep, they advance deeper and deeper into the woods whose shades were most agreeable. Having been at work for nearly two hours, they began to feel a little fatigued and hungry. As the sun was fast advancing toward the meridian, they concluded to rest for a while and eat their lunch. "But," exclaimed Lucille, "where is the basket, my child? Let us go back to the river for we left it in the canoe." At once they start, taking one of the several trails close by. They come to the river, indeed, but no canoe could be seen. "This is not the place we landed at" says Lucille, "my dear Angelica, let us go farther down." So they do, but nowhere a vestige can be seen of their skiff. And no wonder; for, not having been properly hitched, the continual motion of the water had caused the line to become looped, and, at last, the canoe floating free, was carried down the river.

Now, Lucille realized the critical situation they were in, and looking quite earnestly at Angelica, she asks her whether she knows where they are. And, the child, answering very indifferently, "I do not know," she cried out: "Oh, my dear, we are lost! What shall we do? Where shall we go?'' The innocent little girl looks all around as one who is bewildered, and at once bursts in a most pitiful wailing. Lucille embraced her, and, though she is mixing her tears with those of her companion, she tries to console her. Seeing that it was useless to depend any longer on her as guide, she tells her: "Come on, my love, let us go up the river, for I think we left our canoe somewhere higher up." And they began to walk up and down without noticing that they were frequently returning on their steps. They passed the whole of the long afternoon going through the woods, frequently calling loud for help, but they were already too far off, and no one could hear them. And, lo, night came at last. Broken down with hunger and fatigue, they lay on the bare ground for rest.

Meanwhile, as the two girls were in a state of distress, the mind of Mr. Giraud was under a great excitement. The missing of both at usual dinner time was a thing quite unprecedented, but Mr. Giraud did not make much of it, for, the girls being very familiar with the Pappin's family living at a short distance, he supposed that, likely, they had gone visiting their friends. When, however, towards evening he returned from his trading post on the In-ska-pa-shou creek and found out that they were as yet missing, he grew uneasy, and, calling on the Indian boy who was herding his horses, he dispatched him to the Pappin's residence to bring back the two girls, who, in his opinion, most certainly were there. In a very short time the boy returned with the message that they had not been there that day. On hearing this, Giraud clapped his hands, exclaiming: "By Napoleon, where can they have gone?" Here, however, the idea struck him that they might have gone down to the Mission to pay a visit to Mr. E. Chouteau who had repeatedly invited Lucille to go to pass a few days with his wife. And, if such would be the case, they would not return until the next morning. He felt satisfied that certainly this was the case, but, as it was not too late, he told the Indian boy to hurry up with his supper and, after that, to go down to the Chouteaus to ascertain whether the girls were there and return without any delay with an answer. It did not take long for the boy to get through his supper, and off he was, flying in a gallop over the prairie to the Chouteaus, and, finding that the two missing girls were not there, he at once returned home. It was just getting dark. Mr. Giraud was cooling himself on the veranda of his house when, hearing the boy coming on the premises, he hallors at him, saying: "Well, did you find them?" But he answered that they had not been there. At hearing this, the old gentleman cries out in a frantic way: "Oh, my poor children! where are you gone? What has ever happened to you?"

It was too late now, and, the night being very dark, all search after them had to be put off to the next morning. That night was a terrible one for M. Giraud. He could not persuade himself that the two girls were lost, yet it was a cruel fact that both were missing. "Would it be possible" he now and then would say, "that they have been kidnapped by some Indian?" And here all kinds of most villainous crimes would parade before his mind. At times he thinks he hears Lucille crying and calling on him for protection; then he imagines he sees Angelica knocked down senseless by some wicked man, and, in his excitement, beating the air with his clenched fists, he would say: "By my honor, I shall avenge you both my dear children, if I can only find out where you are." This excitement brought upon him a kind of temporary mental aberration. That night he never slept and in his drowziness he would frequently repeat the names of his dear missing ones. At last, the morning of the 29th came, and Mr.Giraud declared that he himself would go in search of his children. Calling on his Brave, an Indian by the name of Kula-shutze (Red Eagle), he tells him to go quick to the prairie and get him his best charger. And, while the Brave is gone, he paces through the timber close to his house thinking on what he should do and where he should first go. Stepping on the familiar path leading to the river, he follows it almost instinctively to the ordinary crossing. Here, noticing that the canoe had gone from its moorings, he wonders who might it be that took it off. At once the idea strikes him that, perhaps, the two girls might have got into it, and, not being able to manage it, might have drowned!

At such an idea, the whole of his body shakes as if struck by an electric flash! He quickly examines the trail and, indeed, sees on it very distinctly the footprints of both the girls as yet fresh on the ground. This settles the question with him; his dear ones are undoubtedly lost, and he begins to moan as a man in despair. The Indians as well as the white employees working on his premises hearing him hasten to come to see what might be the matter, and, after again and again examining the footprints left on the sand, all can come to but one conclusion, that, namely, the two unfortunates must have tried to have some sport with the canoe, they must have capsized, and both were drowned.

All that now remains to be done is to search for the bodies. To this effect, two skiffs are procured, one from Mr. Pappin, the other from Mr. Swiss, and several young men volunteer to run down the river to recover the bodies, if possible. Meanwhile, as this is going on, Mr. Giraud, feeling more nervous than ever, comes to Osage Mission to take advice from Mr. Edward Chouteau concerning the best way to follow in notifying Lucille's parents concerning this most terrible accident. But there was no time to lose. Edward Chouteau quickly calls on his friends and starts them down along the river, sounding the Neosho and searching every nook and point where, generally, large amounts of driftings are left by the main current. This done, he advises Mr. Giraud to return to the house and resign himself to what has happened. "And take time," says he, "do not be too quick in informing Lucille's parents about this unfortunate affair until we get more information."

Twenty-four hours have now passed since the two girls had left home. Having had nothing to eat, after rambling up and down the whole preceding day to no purpose, it is no wonder if both were fatigued and exhausted. In such a condition both lay down on the bare ground to take some rest. Angelica, unconcerned about the dangerous situation they are in, soon falls asleep and looks as happy as a child can be in its couch. Not so with Lucille! That night was a frightful one for her. Indeed, there was no rest for her, not so much on account of the novelty of her lodging, as for the noise kept up during the whole night by the hooting of owls and wild parrots as well as by the confused barking of wolves lurking through the woods in search of some carrion. She had never been used to that sort of serenade and, being naturally most sensitive, her imagination saw terrible visions. She thought that surely hostile Indians were camping in the vicinity and that the noise she heard was coming from them. She trembled for fear, thinking that, after a while, some of them hunting around might discover her and Angelica, and, in such a case, they both would be killed. At last, about daylight, she stands up for a few minutes looking all around and, noticing that everything was quiet, she moves a little further up where the grass seems to be more glossy, and, stretching herself on it, tries to get some sleep, if possible.

And, Lo! meanwhile she is gazing at the morning star lightly rising over the horizon and shining most brilliantly through the trees, she feels as she was charmed by an invisible power and gradually it rapt her into a calm slumber, in which she could have hardly passed a couple of hours, when at once she is awakened by the screaming of Angelica, who, having raised her head and found out that Lucille was no longer by her side, thought herself to have been abandoned by her. Her fear, however, was soon dispelled for in but a few minutes she noticed her companion coming to her. Oh, how happy the poor child did feel in seeing her again. Here both looked around to see whether they might recognize the place they were in, but all in vain. Everything was new to them; silence reigned supreme in the forest and was only occasionally interrupted by sudden gushings of wind through the trees.

This was enough to excite Lucille's curiosity and she makes up her mind to go to find the place and make a good collection before the blasting heat of July would set in. To this effect, she told Angelica, that she intended to go to that hill on the next day, "and you, my child," she said, "do not forget to take a lunch in your basket, that we may not need to come home for dinner." However, noticing that they would have to cross the river in a small canoe, she seems to be perplexed in her mind, and, looking at Angelica with some anxiety she said: "But, my dear child, I see that we will have to cross the diver, and who is going to paddle the skiff for us?" To this Angelica replies "I will; I am well used to it. Whenever Uncle Giraud wants to go to the other side to gather wild onions and strawberries, I always paddle the canoe for him." This answer did fully satisfy Lucille and nothing more was said about it.

The sun had risen as bright as ever and the sky looked as pure as a nice crystal, when, at the balmy breeze of the 28th of June, our florists were out for the West. Hardly had they reached the bank of the river, when, in the twinkling of an eye, Angelica leaped in the canoe and coasting along with masterly hand she invited her companion to come on board. Lucille steps in very cautiously and seats herself at the helm; meanwhile that Angelica softly but steadily begins to row. The water being very calm in but a few minutes they land on the opposite bank.

Here, leaving the lunch basket in the canoe, both spring on terra firma, and, twisting the line of their little boat to a sapling, both start at work. No body living on that side of the river, the ground is literally all dotted with quite a variety of flowers. On they are going at random, picking up only the choicest, and, at every steep, they advance deeper and deeper into the woods whose shades were most agreeable. Having been at work for nearly two hours, they began to feel a little fatigued and hungry. As the sun was fast advancing toward the meridian, they concluded to rest for a while and eat their lunch. "But," exclaimed Lucille, "where is the basket, my child? Let us go back to the river for we left it in the canoe." At once they start, taking one of the several trails close by. They come to the river, indeed, but no canoe could be seen. "This is not the place we landed at" says Lucille, "my dear Angelica, let us go farther down." So they do, but nowhere a vestige can be seen of their skiff. And no wonder; for, not having been properly hitched, the continual motion of the water had caused the line to become looped, and, at last, the canoe floating free, was carried down the river.

Now, Lucille realized the critical situation they were in, and looking quite earnestly at Angelica, she asks her whether she knows where they are. And, the child, answering very indifferently, "I do not know," she cried out: "Oh, my dear, we are lost! What shall we do? Where shall we go?'' The innocent little girl looks all around as one who is bewildered, and at once bursts in a most pitiful wailing. Lucille embraced her, and, though she is mixing her tears with those of her companion, she tries to console her. Seeing that it was useless to depend any longer on her as guide, she tells her: "Come on, my love, let us go up the river, for I think we left our canoe somewhere higher up." And they began to walk up and down without noticing that they were frequently returning on their steps. They passed the whole of the long afternoon going through the woods, frequently calling loud for help, but they were already too far off, and no one could hear them. And, lo, night came at last. Broken down with hunger and fatigue, they lay on the bare ground for rest.

Meanwhile, as the two girls were in a state of distress, the mind of Mr. Giraud was under a great excitement. The missing of both at usual dinner time was a thing quite unprecedented, but Mr. Giraud did not make much of it, for, the girls being very familiar with the Pappin's family living at a short distance, he supposed that, likely, they had gone visiting their friends. When, however, towards evening he returned from his trading post on the In-ska-pa-shou creek and found out that they were as yet missing, he grew uneasy, and, calling on the Indian boy who was herding his horses, he dispatched him to the Pappin's residence to bring back the two girls, who, in his opinion, most certainly were there. In a very short time the boy returned with the message that they had not been there that day. On hearing this, Giraud clapped his hands, exclaiming: "By Napoleon, where can they have gone?" Here, however, the idea struck him that they might have gone down to the Mission to pay a visit to Mr. E. Chouteau who had repeatedly invited Lucille to go to pass a few days with his wife. And, if such would be the case, they would not return until the next morning. He felt satisfied that certainly this was the case, but, as it was not too late, he told the Indian boy to hurry up with his supper and, after that, to go down to the Chouteaus to ascertain whether the girls were there and return without any delay with an answer. It did not take long for the boy to get through his supper, and off he was, flying in a gallop over the prairie to the Chouteaus, and, finding that the two missing girls were not there, he at once returned home. It was just getting dark. Mr. Giraud was cooling himself on the veranda of his house when, hearing the boy coming on the premises, he hallors at him, saying: "Well, did you find them?" But he answered that they had not been there. At hearing this, the old gentleman cries out in a frantic way: "Oh, my poor children! where are you gone? What has ever happened to you?"

It was too late now, and, the night being very dark, all search after them had to be put off to the next morning. That night was a terrible one for M. Giraud. He could not persuade himself that the two girls were lost, yet it was a cruel fact that both were missing. "Would it be possible" he now and then would say, "that they have been kidnapped by some Indian?" And here all kinds of most villainous crimes would parade before his mind. At times he thinks he hears Lucille crying and calling on him for protection; then he imagines he sees Angelica knocked down senseless by some wicked man, and, in his excitement, beating the air with his clenched fists, he would say: "By my honor, I shall avenge you both my dear children, if I can only find out where you are." This excitement brought upon him a kind of temporary mental aberration. That night he never slept and in his drowziness he would frequently repeat the names of his dear missing ones. At last, the morning of the 29th came, and Mr.Giraud declared that he himself would go in search of his children. Calling on his Brave, an Indian by the name of Kula-shutze (Red Eagle), he tells him to go quick to the prairie and get him his best charger. And, while the Brave is gone, he paces through the timber close to his house thinking on what he should do and where he should first go. Stepping on the familiar path leading to the river, he follows it almost instinctively to the ordinary crossing. Here, noticing that the canoe had gone from its moorings, he wonders who might it be that took it off. At once the idea strikes him that, perhaps, the two girls might have got into it, and, not being able to manage it, might have drowned!

At such an idea, the whole of his body shakes as if struck by an electric flash! He quickly examines the trail and, indeed, sees on it very distinctly the footprints of both the girls as yet fresh on the ground. This settles the question with him; his dear ones are undoubtedly lost, and he begins to moan as a man in despair. The Indians as well as the white employees working on his premises hearing him hasten to come to see what might be the matter, and, after again and again examining the footprints left on the sand, all can come to but one conclusion, that, namely, the two unfortunates must have tried to have some sport with the canoe, they must have capsized, and both were drowned.

All that now remains to be done is to search for the bodies. To this effect, two skiffs are procured, one from Mr. Pappin, the other from Mr. Swiss, and several young men volunteer to run down the river to recover the bodies, if possible. Meanwhile, as this is going on, Mr. Giraud, feeling more nervous than ever, comes to Osage Mission to take advice from Mr. Edward Chouteau concerning the best way to follow in notifying Lucille's parents concerning this most terrible accident. But there was no time to lose. Edward Chouteau quickly calls on his friends and starts them down along the river, sounding the Neosho and searching every nook and point where, generally, large amounts of driftings are left by the main current. This done, he advises Mr. Giraud to return to the house and resign himself to what has happened. "And take time," says he, "do not be too quick in informing Lucille's parents about this unfortunate affair until we get more information."

Twenty-four hours have now passed since the two girls had left home. Having had nothing to eat, after rambling up and down the whole preceding day to no purpose, it is no wonder if both were fatigued and exhausted. In such a condition both lay down on the bare ground to take some rest. Angelica, unconcerned about the dangerous situation they are in, soon falls asleep and looks as happy as a child can be in its couch. Not so with Lucille! That night was a frightful one for her. Indeed, there was no rest for her, not so much on account of the novelty of her lodging, as for the noise kept up during the whole night by the hooting of owls and wild parrots as well as by the confused barking of wolves lurking through the woods in search of some carrion. She had never been used to that sort of serenade and, being naturally most sensitive, her imagination saw terrible visions. She thought that surely hostile Indians were camping in the vicinity and that the noise she heard was coming from them. She trembled for fear, thinking that, after a while, some of them hunting around might discover her and Angelica, and, in such a case, they both would be killed. At last, about daylight, she stands up for a few minutes looking all around and, noticing that everything was quiet, she moves a little further up where the grass seems to be more glossy, and, stretching herself on it, tries to get some sleep, if possible.

And, Lo! meanwhile she is gazing at the morning star lightly rising over the horizon and shining most brilliantly through the trees, she feels as she was charmed by an invisible power and gradually it rapt her into a calm slumber, in which she could have hardly passed a couple of hours, when at once she is awakened by the screaming of Angelica, who, having raised her head and found out that Lucille was no longer by her side, thought herself to have been abandoned by her. Her fear, however, was soon dispelled for in but a few minutes she noticed her companion coming to her. Oh, how happy the poor child did feel in seeing her again. Here both looked around to see whether they might recognize the place they were in, but all in vain. Everything was new to them; silence reigned supreme in the forest and was only occasionally interrupted by sudden gushings of wind through the trees.

"We are lost; have nothing to eat; are going to die. O, you that happen to find our remains, for God's sake bury us both together. Lucille and Angelica, June 29th, 1847."

"We are lost; have nothing to eat; are going to die. O, you that happen to find our remains, for God's sake bury us both together. Lucille and Angelica, June 29th, 1847."

Lucille had been educated by pious and devout parents, who, from her childhood, had taught her to fear God and, at the same time, to trust in His assistance, especially in moments of danger. Now, the unexpected adventure calls to her mind all those salutary teachings, and, full of confidence in God's power, looking at Angelica with motherly love, "My dear child." she says, "we are lost and likely will have to die in these woods. God, however, can save us both if it so pleases Him. Let us both kneel down and pray to Him to be merciful to us." Having said this, both kneel and pray most fervently for a while. Next, standing up to see in what direction they had better go, they conclude to follow up the river, always in hopes of finding their canoe. And, now they are starting when an idea strikes Lucille's mind and she says to herself, why could we not leave here some mark that we might recognize the place in case that in our wandering around, we might return to this spot. Besides, who knows that after time, people, passing by this place, directed by this mark, may find our remains and notify our friends about our death. Here she takes from her head a large red silk handkerchief and tied it to a limb of a tree standing by and overlooking the river. Next, noticing at a short distance a buffalo's skull well bleached by the weather, she writes on the flat bone of the fore-head: "We are lost; have nothing to eat; are going to die. O, you that happen to find our remains, for God's sake bury us both together. Lucille and Angelica, June 29th, 1847." Having placed the skull in a showing position at the foot of the same tree, they go along through the woods, not knowing where, and look for wild fruits for both are hungry.

The men sent by Edward Chouteau to look for the bodies of the supposed drowned girls returned about sun-down saying that they had neither found or heard anything concerning them and, as the river was yet high and its current quite swift, it would be useless to look after them any further, for by this time they were out of reach. Hearing this Edward showed great distress in his countenance and, after a while, exclaimed: "Poor girls; this is too bad, but no one can help it.'' The sun had sunk in the far west and in Edward's house it looked as if a funeral had taken place in it. Knowing with what anxiety Mr. Giraud was expecting some information, he springs on his horse and hurries to his friend's residence. He finds him pacing to and fro on his veranda. As soon as Giraud notices his coming, he calls on him with great excitement, saying: "Well, what news, my friend?" "No news," was the cool reply that sounded through the air. This answer strikes Mr. Giraud as if it had been a thunderclap. Tears streamed from his eyes. His sobs for a while do not allow him to utter a single word. At last he cries out: "My dear friend, we will have to give them up! But, tell me, what shall I write to Lucille's father? He had trusted her to my care; he wanted me to be a father to her, and I have lost her, and so have I lost her that I can give no account of her. Oh, Edward, get me out of this trouble; do you write for me to him, for my grief is such I am unable to do it." Mr. Edward promised that he would attend to it, and returned to his family.

He hardly had gone when a sturdy young man, by the name of Isaac Swiss, an Osage half-breed, who was taking care of Mr. Giraud's store on the "In-ska-pashu", stepped in and, throwing on the floor half a dozen of nice ducks, said : "Mr. Giraud, here I am, as you see; today I had very good luck; I did not miss a single shot, but I was not quick enough to overtake a big deer, whom I met at the crossing of the creek. As the fellow sighted me, he whirled at once, and, upon my word, he did jump and run. il never before did see the like. I followed him through the timber between brush and briars, when the buck plunged into the river and swam to the other side. I lost my game." Having given his account of his adventure, he sat down to fix up his pipe and have a good smoke. Then he continued: "Mr. Giraud, trade is very good at present, but when will your summer goods come in? The Indians are anxious to leave on the usual hunt but have neither powder nor lead. In how many days do you think our teams will return from Kansas City?" "In a few days" Mr. Giraud replied, "my goods are due, but the late rains made the roads so bad that the boys cannot travel fast." "But, now," said he, "you had better go to take your supper for it is getting late."

After supper Isaac returned to the veranda to enjoy the fresh air, and, seating himself comfortably on an old box, fills up his pipe and, having emitted from his mouth two big puffs of smoke, he said : "well, Mr. Giraud, "did you, today, see any of the surveyors?" "Why, no," replied the old gentleman, asking: "Did you see any of them.''" "O, no, sir," he answered, "but I saw their signal about two miles below our store. I suppose they must have crossed the river south of our Trading Post." "Why, is it possible?" Giraud remarked with some excitement, "this is good news, Isaac! I, indeed have not seen any of them to-day, but, as you well know, I am expecting them, for, as I told you other times, they are talking of opening a coach road from Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and it would be of great advantage to us if this road would pass by our store. Now, tell me, Isaac, do you think the river will be fordable by tomorrow morning?" "Not at this point" was Isaac's reply; "but," said he, "it will be likely fordable at the upper crossing." Here Mr. Giraud stood up and said: "Well, I think so, myself. See, now, my boy, we must not lose the opportunity of seeing these surveyors, and induce them by all means to run the road by our store for this would increase our business considerably. I think the best we can do will be that tomorrow morning we hurry up and overtake them; I am confident we will succeed."

And now Mr. Giraud retired to his room for rest. Isaac needs neither room nor bed; he just lies down on a pile of buffalo robes under the porch, and, as the cowboys are used to say, he soon sleeps as sound as a log. The morning of the 30th was as bright as one could wish it. A gentle breeze from the east was cooling the atmosphere and making it very agreeable for an early riding. Mr. Giraud and Isaac were both on the move in search of the surveyors. Coming to the upper ford of the Neosho, they had no difficulty in crossing it. "Now," Mr. Giraud asked Isaac, "on what direction was it that you saw the flag," Isaac pointed to the west. Then both turn their course up the river between brushwood and fallen trees, following no road, for, in fact, there was none. They had been going for about half an hour, when Isaac, always in good humor, cried out: "Hello, Mr. Giraud, look way yonder; there is the surveyor's flag. "Why," replied Giraud, after looking at it very attentively, "that is not the regular flag, but, perhaps, they have dropped the real one somewhere and that might be a substitute for it. Anyway let us keep on and, once we will be on their tracks, we will soon overtake them, for they cannot be very far. However, as we do not know what kind of people we might meet, let us load our guns to be ready for our defense, if needed, for you know, my boy, that of the several negroes who ran away from their masters in Missouri have been nestling through these woods and they are a very desperate set of fellows.

The men sent by Edward Chouteau to look for the bodies of the supposed drowned girls returned about sun-down saying that they had neither found or heard anything concerning them and, as the river was yet high and its current quite swift, it would be useless to look after them any further, for by this time they were out of reach. Hearing this Edward showed great distress in his countenance and, after a while, exclaimed: "Poor girls; this is too bad, but no one can help it.'' The sun had sunk in the far west and in Edward's house it looked as if a funeral had taken place in it. Knowing with what anxiety Mr. Giraud was expecting some information, he springs on his horse and hurries to his friend's residence. He finds him pacing to and fro on his veranda. As soon as Giraud notices his coming, he calls on him with great excitement, saying: "Well, what news, my friend?" "No news," was the cool reply that sounded through the air. This answer strikes Mr. Giraud as if it had been a thunderclap. Tears streamed from his eyes. His sobs for a while do not allow him to utter a single word. At last he cries out: "My dear friend, we will have to give them up! But, tell me, what shall I write to Lucille's father? He had trusted her to my care; he wanted me to be a father to her, and I have lost her, and so have I lost her that I can give no account of her. Oh, Edward, get me out of this trouble; do you write for me to him, for my grief is such I am unable to do it." Mr. Edward promised that he would attend to it, and returned to his family.

He hardly had gone when a sturdy young man, by the name of Isaac Swiss, an Osage half-breed, who was taking care of Mr. Giraud's store on the "In-ska-pashu", stepped in and, throwing on the floor half a dozen of nice ducks, said : "Mr. Giraud, here I am, as you see; today I had very good luck; I did not miss a single shot, but I was not quick enough to overtake a big deer, whom I met at the crossing of the creek. As the fellow sighted me, he whirled at once, and, upon my word, he did jump and run. il never before did see the like. I followed him through the timber between brush and briars, when the buck plunged into the river and swam to the other side. I lost my game." Having given his account of his adventure, he sat down to fix up his pipe and have a good smoke. Then he continued: "Mr. Giraud, trade is very good at present, but when will your summer goods come in? The Indians are anxious to leave on the usual hunt but have neither powder nor lead. In how many days do you think our teams will return from Kansas City?" "In a few days" Mr. Giraud replied, "my goods are due, but the late rains made the roads so bad that the boys cannot travel fast." "But, now," said he, "you had better go to take your supper for it is getting late."

After supper Isaac returned to the veranda to enjoy the fresh air, and, seating himself comfortably on an old box, fills up his pipe and, having emitted from his mouth two big puffs of smoke, he said : "well, Mr. Giraud, "did you, today, see any of the surveyors?" "Why, no," replied the old gentleman, asking: "Did you see any of them.''" "O, no, sir," he answered, "but I saw their signal about two miles below our store. I suppose they must have crossed the river south of our Trading Post." "Why, is it possible?" Giraud remarked with some excitement, "this is good news, Isaac! I, indeed have not seen any of them to-day, but, as you well know, I am expecting them, for, as I told you other times, they are talking of opening a coach road from Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and it would be of great advantage to us if this road would pass by our store. Now, tell me, Isaac, do you think the river will be fordable by tomorrow morning?" "Not at this point" was Isaac's reply; "but," said he, "it will be likely fordable at the upper crossing." Here Mr. Giraud stood up and said: "Well, I think so, myself. See, now, my boy, we must not lose the opportunity of seeing these surveyors, and induce them by all means to run the road by our store for this would increase our business considerably. I think the best we can do will be that tomorrow morning we hurry up and overtake them; I am confident we will succeed."

And now Mr. Giraud retired to his room for rest. Isaac needs neither room nor bed; he just lies down on a pile of buffalo robes under the porch, and, as the cowboys are used to say, he soon sleeps as sound as a log. The morning of the 30th was as bright as one could wish it. A gentle breeze from the east was cooling the atmosphere and making it very agreeable for an early riding. Mr. Giraud and Isaac were both on the move in search of the surveyors. Coming to the upper ford of the Neosho, they had no difficulty in crossing it. "Now," Mr. Giraud asked Isaac, "on what direction was it that you saw the flag," Isaac pointed to the west. Then both turn their course up the river between brushwood and fallen trees, following no road, for, in fact, there was none. They had been going for about half an hour, when Isaac, always in good humor, cried out: "Hello, Mr. Giraud, look way yonder; there is the surveyor's flag. "Why," replied Giraud, after looking at it very attentively, "that is not the regular flag, but, perhaps, they have dropped the real one somewhere and that might be a substitute for it. Anyway let us keep on and, once we will be on their tracks, we will soon overtake them, for they cannot be very far. However, as we do not know what kind of people we might meet, let us load our guns to be ready for our defense, if needed, for you know, my boy, that of the several negroes who ran away from their masters in Missouri have been nestling through these woods and they are a very desperate set of fellows.

"Isaac, oh, dear, this is Lucille's handkerchief! Yes, I know it well; I bet her mark is on it!"

"Isaac, oh, dear, this is Lucille's handkerchief! Yes, I know it well; I bet her mark is on it!"

Both loaded their rifles and on they kept traveling till they came to the place and saw that the supposed flag was nothing else than a red silk handkerchief hanging from a branch of a tree. Mr. Giraud looked at it most carefully, and, at once, exclaimed: "Isaac, oh, dear, this is Lucille's handkerchief! Yes, I know it well; I bet her mark is on it!" Alighting in a great hurry, he almost steps on the buffalo skull, which stood at the foot of the tree. At first, he had not taken notice of it, but now, as it was in his way, he looks at it with attention and sees some writing on it

At the sight of that writing, he seems to be bewildered; just as if he had seen a ghost. A convulsive sensation comes over him; he looks as if he were under the influence of a charm. However, he soon recovers his presence of mind, and stooping down he reads the writing. He recognizes the hand; he understands the meaning of the notice, and, standing up, with a countenance full of excitement, he cries out: "Thanks be to God we came on their tracks; they may, as yet, be alive! O, Isaac; I now know all about it. This is not a surveyor's flag, as you thought, but it is a signal of distress put up yesterday by Lucille and Angelica. Who knows where they may be at present! But, they cannot be very far from this place. We must find them. Suppose you keep going on west along the river and I shall at the same time go south. Not to get astray one from the other let us have an understanding. If you happen to meet them, fire, at once, two consecutive shots, and I shall come to you. In the case I should find them I shall do the same, and you will come to me straight off.

Here they start leading their horses by the bridle, stepping very cautiously, and taking notice of every inch of ground as they advance on their way. Mr. Giraud has already walked a distance of nearly two miles, when he discovered them. They both were lying on the ground, apparently as if sleeping. It is easier to imagine than to describe what were the feelings of the old gentleman at that moment. He first calls on Lucille, next on Angelica, but receives no answer. He approaches more closely and sees that they are alive, but in such a state of exhaustion that they are unable to speak or move. However, they are both conscious, and, seeing the familiar face of their friend, their eyes sparkle with joy, a smile comes on their lips. Mr. Giraud, without any delay, gives the conventional sign, and, in a short time, Isaac is galloping to the spot. As soon as the old gentleman sees him coming, he exclaims: "My boy, hurry home as fast as you can and tell Wha-Ta-hinka that I found my two children; they are both living, but so weak that for a couple of days they won't be able to move from this place. Tell him to stop all other work, and bring his wife here to take care of them. Next tell my housekeeper to give you a lunch for them for they had nothing to eat during the two last days." Isaac did as he was ordered, and in about two hours returned with the lunch.

Wha-ta-hinka, who was an old and faithful servant of Giraud's family, understood at once what the emergency was calling for. He quickly had a couple of pacing horses ready, and, in the afternoon, he and his wife came with a regular outfit and plenty of provisions.

As he was approaching to the place, his wife began to cry and lament in a most heartrending strain, just as if she had lost some of her children. She kept up her doleful tune for quite a while, as it is customary among the Osages when they meet a friend they have not seen for a long time. And. having complied with what she looked upon as a duty of sympathy, she goes to work and in less than one hour she had put up a very comfortable wigwam. In this Mr. Giraud, with that adroitness characteristic of a French gentleman, moved his two protégées, and, seeing that the good squaw had brought with her an abundance of whatever might be needed, he returned to his house and dispatched Isaac down to Osage Mission to inform Mr. Chouteau of all that had happened. The good news soon spread all around, and people all over the settlement felt happy in hearing how the two missing girls had been found.

By the end of 3 days, the 3rd of July, they had both recovered and were able to return home. Now, all Giraud's friends came to congratulate him and wished to hear from Lucille the account of their adventure. And she would again and again repeat all the story of their getting lost when looking after flowers; how, having missed their canoe, they became confused in mind and, not knowing the place, they kept moving to and fro without perceiving that they were going astray, and most certainly they would have died of exhaustion had not God in His mercy directed Mr. Giraud to their steps.

And now, that everything was again running in good order, Mr. Giraud, willing to show how happy he felt for having recovered his dear children, sent a runner to inform all his friends that on the coming of the next full moon he would have a great feast and wanted them to know that everyone was invited to it. To make the invitation more attractive, he announced the following programme, namely, eight large beeves would be killed and everyone would have plenty to eat. During the day there would be different amusements, such as ball-play, horse-races, foot-races, sack-races and at night would take place a grand war dance. In a word, nothing would be omitted that might anyway contribute to render the feast most agreeable to all

Lucille never expected that Mr. Giraud would give such a public and solemn mark of joy and go into such an expense on her account. She felt very much confused, and calling on him, she said: "My dear friend, I am under a thousand obligations to you for the way you have treated me since my coming to your house, but, most particularly, I am indebted to you for having saved my life. And now, I feel very proud for the honor you intend to bring me by inviting all the Osages to come and feast on my account, but, please listen to me for one moment; before that day comes, I wish you to do me a favor.

You must know that on the morning that I hung my handkerchief to the tree on which you found it, I and Angelica calculated to travel the whole day in search of our canoe. However, being sure that we were lost, and, knowing that without a special assistance of God, we would never be able to get out of our terrible situation, before going any farther we both knelt down and prayed to God to save us; nay, we promised that if we would ever return home, we would go to Osage Mission church and offer our thanksgiving to God through the hands of the Immaculate Virgin. Having finished our prayer, we started, but we had hardly advanced two miles, when a heavy dizziness came over us. We staggered and fell; we were so weak that we could no longer speak and remained in such state till God directed you to find us. Now, it would not be right for us to take part in such a public rejoicing as you are preparing on our account, without first going down to the Mission to fulfill our vow.

To this most earnest request Mr. Giraud replied very kindly that they were right in being thankful to God for, indeed, they had a very narrow escape. "For," said he, '*it was a very great wonder that you both did not perish in those woods, as has been the case with several others before you. The coming of Isaac to my house was really providential, and neither he nor I had the slightest idea of going in search of you when we rode out to look for the supposed surveying party. As, therefore, God has heard your prayers, it is most proper for you to give Him thanks. Hence, whenever you make up your mind to go down to the Fathers' Church, let me know and I, myself, shall have the pleasure of bringing you there." Lucille and Angelica having agreed to go to the Mission on the next day, Mr. Giraud told them that he would be ready to comply with their wishes. In fact, about 10:30 the next morning, he started with both of them and by noon they were alighting on Edward Chouteau's premises. There is no need of telling with what most sincere marks of affection they were received. Mrs. Rosalia, Edward Chouteau's wife, was almost out of herself for joy in seeing two most dear friends over whose supposed loss, but a few days before, she had shed so many tears. Towards evening, the two girls, accompanied by Mrs. Rosalia, came up to the Mission to make arrangements with Father Schoenmakers. The Father felt very happy in seeing them and told them that at 7 o'clock the next morning Father John Bax would be ready to offer up the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass for them.

On the next day, at the appointed hour, they came up to the church together with a number of their friends. The two girls, each one carrying a beautiful bouquet of the choicest flowers the season could afford, after bowing before the image of the Immaculate Virgin, laid their offering on the altar. Here Father Bax begins the Mass, during which he addresses a few appropriate words to the people, advising them to always trust in the kind assistance of Divine Providence, and never to forget to be thankful for favors received. Mass being over, the whole party returned to the Chouteaus, where throughout the whole day, large numbers of Indians came to congratulate the two girls. And now the full moon of July has come. Though in midsummer, a gentle breeze which is prevailing promises a nice day for out-door exercises. Since very early in the morning the town crier has been proclaiming with a stentorian voice the programme of the feast, calling all to come and take part in the common rejoicing. The wide rolling prairie east of Mr. Giraud's residence is the chosen spot where the feast is to be celebrated.

A number of Osages who have come during the preceding night are stirring about and looking after their horses. The squaws are at work; some stretching awnings, others making temporary lodges. Stout looking young girls are going to the next timber to gather dry wood to make fire; meanwhile others are busy packing water from the Neosho up to their camps. Quite a crowd of frolicking children are gamboling around, playing all sorts of antics, and diving into the river like a flock of ducks. As the sun is getting higher, the hum of many voices, resembling the murmuring of the wind through a forest, is on the increase, and one might fancy he was transported by magic to one of the most frequented thoroughfares of a large city where a big market is going on.

At an early hour Mr. Giraud sends for the principal men and makes them a present of eight fat beeves, requesting them to see that each family has a good share in the distribution of the meat. A party of Braves, having driven the steers to a nook of the prairie close to the timber, butcher them at once, and allow everyone to have as much of meat as they need. At 2:30 P. M., the Kettletender, whose duty is to superintend feasts of this kind, takes his buffalo drum, and accompanied by a few young men, marches to the center of the ground allotted for the sports and having enkindled a fire, they sit around it and began to sing their traditional Tho-hi-hun to the sound of their tom-tom.

Now everyone knows that the time for the public games has come. Behold long lines of men, women and children, all wrapt in gorgeous blankets of different colors, moving from every direction, all coming to take their seats on the green sod, according to their different clans. On the higher part of the prairie Lucille and Angelica, the heroines of the feast, occupy chairs of honor. Next to them are Michael Giraud and Edward Chouteau and his wife. The balance of the people are squatting on the grass, forming, as it were, two large wings, brilliant for the variety of the nice colored blankets and the richly embroidered tunics and leggings worn by them.

A war whoop opens the entertainment. Numbers of young Bucks whose bodies are all bedaubed with showing colors, advance to the center of the arena, and, without any preliminaries, begin to play foot ball. Their appearance is that of a gang of Satyrs emerging from the near forest. So rapid and grotesque are their evolutions, that they seem to have all their limbs duplicated, so quick are they turning up and down to catch the ball. This play is followed by several others, but that which gives more merriment than all is the sack-race. In this the competitors are twelve boys about fifteen years old. Mr. Giraud himself helps them to get into their sacks, and Lucille has the fun of tying the same around their neck. They stand all in a row, looking like Egyptian mummies. Here Lucille claps her hands, and, lo, they all start. But, alas, they had advanced only a few steps when, at once losing their balance, one after another all tumble to the ground. And, spite of all their efforts, none of them can ever succeed in getting up for in trying to arise they entrap themselves more and more and are again brought down. The whole is a real treat for the people who, seeing the vain efforts made by the poor fellows in order to arise on their feet, are laughing most merrily, and try to encourage them with great vociferations to try once more. The noise now following is such that the boys become excited and no longer know what to do.

However, always confident that with a quick move upward they might succeed in taking a standing posture and go a few steps farther, they now and then make a dash, as it were, at the air, but with no result, for they fall again and roll over the grass to the great amusement of the people. And now Lucille thought that this play had been going on long enough and requested Mr. Giraud to let the boys out of their sacks, and, since they all had contributed so much to the general merriment, she declared that it was but right that each one should receive a premium. Mr. Giraud agreed perfectly with her, and immediately handed to her twelve nice red scarfs, of which she presented one to each of the boys.

This most amusing entertainment was followed by horse racing. These races took place in succession; the first being run by ten horses; the second by four; that is to say, those four who proved to be the best in the preceding, and the two who were superior in this, ran the third, the swiftest of the two receiving the premium. The young men who ran the horses had no hindrance of any sort on their persons the different colors with which they were painted all over making most all the garments they had on. They rode their steeds bare-back with no other bridle than a thin lariat twisted around the lower jaw of the beast, and, as in riding they were leaning on the neck of their horses having their feet entwined with the forelegs of the same, looking at them from a distance one could not but fancy he saw a squad of Centaurs running over the country, for they seemed to have but one boy with their horses.

The races were a success, and Lucille felt very proud when she was requested to hand the prize to the winner. With this the greatest part of the programme was over and the people returned to their camps.

The twilight was fast passing away and night gradually spreading its darkness, like a pall, over the earth, when a beautiful full moon appeared with silvery radiance, to enlighten the whole country. Hark! the tom-tom is again sounding and all the men quickly arising don their blankets; the squaws huddle their smaller children on their neck and, driving the balance of their little ones before them, following one another in a long line, return to the play ground to assist at a great war dance.

At the sight of that writing, he seems to be bewildered; just as if he had seen a ghost. A convulsive sensation comes over him; he looks as if he were under the influence of a charm. However, he soon recovers his presence of mind, and stooping down he reads the writing. He recognizes the hand; he understands the meaning of the notice, and, standing up, with a countenance full of excitement, he cries out: "Thanks be to God we came on their tracks; they may, as yet, be alive! O, Isaac; I now know all about it. This is not a surveyor's flag, as you thought, but it is a signal of distress put up yesterday by Lucille and Angelica. Who knows where they may be at present! But, they cannot be very far from this place. We must find them. Suppose you keep going on west along the river and I shall at the same time go south. Not to get astray one from the other let us have an understanding. If you happen to meet them, fire, at once, two consecutive shots, and I shall come to you. In the case I should find them I shall do the same, and you will come to me straight off.

Here they start leading their horses by the bridle, stepping very cautiously, and taking notice of every inch of ground as they advance on their way. Mr. Giraud has already walked a distance of nearly two miles, when he discovered them. They both were lying on the ground, apparently as if sleeping. It is easier to imagine than to describe what were the feelings of the old gentleman at that moment. He first calls on Lucille, next on Angelica, but receives no answer. He approaches more closely and sees that they are alive, but in such a state of exhaustion that they are unable to speak or move. However, they are both conscious, and, seeing the familiar face of their friend, their eyes sparkle with joy, a smile comes on their lips. Mr. Giraud, without any delay, gives the conventional sign, and, in a short time, Isaac is galloping to the spot. As soon as the old gentleman sees him coming, he exclaims: "My boy, hurry home as fast as you can and tell Wha-Ta-hinka that I found my two children; they are both living, but so weak that for a couple of days they won't be able to move from this place. Tell him to stop all other work, and bring his wife here to take care of them. Next tell my housekeeper to give you a lunch for them for they had nothing to eat during the two last days." Isaac did as he was ordered, and in about two hours returned with the lunch.

Wha-ta-hinka, who was an old and faithful servant of Giraud's family, understood at once what the emergency was calling for. He quickly had a couple of pacing horses ready, and, in the afternoon, he and his wife came with a regular outfit and plenty of provisions.

As he was approaching to the place, his wife began to cry and lament in a most heartrending strain, just as if she had lost some of her children. She kept up her doleful tune for quite a while, as it is customary among the Osages when they meet a friend they have not seen for a long time. And. having complied with what she looked upon as a duty of sympathy, she goes to work and in less than one hour she had put up a very comfortable wigwam. In this Mr. Giraud, with that adroitness characteristic of a French gentleman, moved his two protégées, and, seeing that the good squaw had brought with her an abundance of whatever might be needed, he returned to his house and dispatched Isaac down to Osage Mission to inform Mr. Chouteau of all that had happened. The good news soon spread all around, and people all over the settlement felt happy in hearing how the two missing girls had been found.

By the end of 3 days, the 3rd of July, they had both recovered and were able to return home. Now, all Giraud's friends came to congratulate him and wished to hear from Lucille the account of their adventure. And she would again and again repeat all the story of their getting lost when looking after flowers; how, having missed their canoe, they became confused in mind and, not knowing the place, they kept moving to and fro without perceiving that they were going astray, and most certainly they would have died of exhaustion had not God in His mercy directed Mr. Giraud to their steps.

And now, that everything was again running in good order, Mr. Giraud, willing to show how happy he felt for having recovered his dear children, sent a runner to inform all his friends that on the coming of the next full moon he would have a great feast and wanted them to know that everyone was invited to it. To make the invitation more attractive, he announced the following programme, namely, eight large beeves would be killed and everyone would have plenty to eat. During the day there would be different amusements, such as ball-play, horse-races, foot-races, sack-races and at night would take place a grand war dance. In a word, nothing would be omitted that might anyway contribute to render the feast most agreeable to all

Lucille never expected that Mr. Giraud would give such a public and solemn mark of joy and go into such an expense on her account. She felt very much confused, and calling on him, she said: "My dear friend, I am under a thousand obligations to you for the way you have treated me since my coming to your house, but, most particularly, I am indebted to you for having saved my life. And now, I feel very proud for the honor you intend to bring me by inviting all the Osages to come and feast on my account, but, please listen to me for one moment; before that day comes, I wish you to do me a favor.

You must know that on the morning that I hung my handkerchief to the tree on which you found it, I and Angelica calculated to travel the whole day in search of our canoe. However, being sure that we were lost, and, knowing that without a special assistance of God, we would never be able to get out of our terrible situation, before going any farther we both knelt down and prayed to God to save us; nay, we promised that if we would ever return home, we would go to Osage Mission church and offer our thanksgiving to God through the hands of the Immaculate Virgin. Having finished our prayer, we started, but we had hardly advanced two miles, when a heavy dizziness came over us. We staggered and fell; we were so weak that we could no longer speak and remained in such state till God directed you to find us. Now, it would not be right for us to take part in such a public rejoicing as you are preparing on our account, without first going down to the Mission to fulfill our vow.

To this most earnest request Mr. Giraud replied very kindly that they were right in being thankful to God for, indeed, they had a very narrow escape. "For," said he, '*it was a very great wonder that you both did not perish in those woods, as has been the case with several others before you. The coming of Isaac to my house was really providential, and neither he nor I had the slightest idea of going in search of you when we rode out to look for the supposed surveying party. As, therefore, God has heard your prayers, it is most proper for you to give Him thanks. Hence, whenever you make up your mind to go down to the Fathers' Church, let me know and I, myself, shall have the pleasure of bringing you there." Lucille and Angelica having agreed to go to the Mission on the next day, Mr. Giraud told them that he would be ready to comply with their wishes. In fact, about 10:30 the next morning, he started with both of them and by noon they were alighting on Edward Chouteau's premises. There is no need of telling with what most sincere marks of affection they were received. Mrs. Rosalia, Edward Chouteau's wife, was almost out of herself for joy in seeing two most dear friends over whose supposed loss, but a few days before, she had shed so many tears. Towards evening, the two girls, accompanied by Mrs. Rosalia, came up to the Mission to make arrangements with Father Schoenmakers. The Father felt very happy in seeing them and told them that at 7 o'clock the next morning Father John Bax would be ready to offer up the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass for them.

On the next day, at the appointed hour, they came up to the church together with a number of their friends. The two girls, each one carrying a beautiful bouquet of the choicest flowers the season could afford, after bowing before the image of the Immaculate Virgin, laid their offering on the altar. Here Father Bax begins the Mass, during which he addresses a few appropriate words to the people, advising them to always trust in the kind assistance of Divine Providence, and never to forget to be thankful for favors received. Mass being over, the whole party returned to the Chouteaus, where throughout the whole day, large numbers of Indians came to congratulate the two girls. And now the full moon of July has come. Though in midsummer, a gentle breeze which is prevailing promises a nice day for out-door exercises. Since very early in the morning the town crier has been proclaiming with a stentorian voice the programme of the feast, calling all to come and take part in the common rejoicing. The wide rolling prairie east of Mr. Giraud's residence is the chosen spot where the feast is to be celebrated.

A number of Osages who have come during the preceding night are stirring about and looking after their horses. The squaws are at work; some stretching awnings, others making temporary lodges. Stout looking young girls are going to the next timber to gather dry wood to make fire; meanwhile others are busy packing water from the Neosho up to their camps. Quite a crowd of frolicking children are gamboling around, playing all sorts of antics, and diving into the river like a flock of ducks. As the sun is getting higher, the hum of many voices, resembling the murmuring of the wind through a forest, is on the increase, and one might fancy he was transported by magic to one of the most frequented thoroughfares of a large city where a big market is going on.

At an early hour Mr. Giraud sends for the principal men and makes them a present of eight fat beeves, requesting them to see that each family has a good share in the distribution of the meat. A party of Braves, having driven the steers to a nook of the prairie close to the timber, butcher them at once, and allow everyone to have as much of meat as they need. At 2:30 P. M., the Kettletender, whose duty is to superintend feasts of this kind, takes his buffalo drum, and accompanied by a few young men, marches to the center of the ground allotted for the sports and having enkindled a fire, they sit around it and began to sing their traditional Tho-hi-hun to the sound of their tom-tom.

Now everyone knows that the time for the public games has come. Behold long lines of men, women and children, all wrapt in gorgeous blankets of different colors, moving from every direction, all coming to take their seats on the green sod, according to their different clans. On the higher part of the prairie Lucille and Angelica, the heroines of the feast, occupy chairs of honor. Next to them are Michael Giraud and Edward Chouteau and his wife. The balance of the people are squatting on the grass, forming, as it were, two large wings, brilliant for the variety of the nice colored blankets and the richly embroidered tunics and leggings worn by them.

A war whoop opens the entertainment. Numbers of young Bucks whose bodies are all bedaubed with showing colors, advance to the center of the arena, and, without any preliminaries, begin to play foot ball. Their appearance is that of a gang of Satyrs emerging from the near forest. So rapid and grotesque are their evolutions, that they seem to have all their limbs duplicated, so quick are they turning up and down to catch the ball. This play is followed by several others, but that which gives more merriment than all is the sack-race. In this the competitors are twelve boys about fifteen years old. Mr. Giraud himself helps them to get into their sacks, and Lucille has the fun of tying the same around their neck. They stand all in a row, looking like Egyptian mummies. Here Lucille claps her hands, and, lo, they all start. But, alas, they had advanced only a few steps when, at once losing their balance, one after another all tumble to the ground. And, spite of all their efforts, none of them can ever succeed in getting up for in trying to arise they entrap themselves more and more and are again brought down. The whole is a real treat for the people who, seeing the vain efforts made by the poor fellows in order to arise on their feet, are laughing most merrily, and try to encourage them with great vociferations to try once more. The noise now following is such that the boys become excited and no longer know what to do.

However, always confident that with a quick move upward they might succeed in taking a standing posture and go a few steps farther, they now and then make a dash, as it were, at the air, but with no result, for they fall again and roll over the grass to the great amusement of the people. And now Lucille thought that this play had been going on long enough and requested Mr. Giraud to let the boys out of their sacks, and, since they all had contributed so much to the general merriment, she declared that it was but right that each one should receive a premium. Mr. Giraud agreed perfectly with her, and immediately handed to her twelve nice red scarfs, of which she presented one to each of the boys.

This most amusing entertainment was followed by horse racing. These races took place in succession; the first being run by ten horses; the second by four; that is to say, those four who proved to be the best in the preceding, and the two who were superior in this, ran the third, the swiftest of the two receiving the premium. The young men who ran the horses had no hindrance of any sort on their persons the different colors with which they were painted all over making most all the garments they had on. They rode their steeds bare-back with no other bridle than a thin lariat twisted around the lower jaw of the beast, and, as in riding they were leaning on the neck of their horses having their feet entwined with the forelegs of the same, looking at them from a distance one could not but fancy he saw a squad of Centaurs running over the country, for they seemed to have but one boy with their horses.

The races were a success, and Lucille felt very proud when she was requested to hand the prize to the winner. With this the greatest part of the programme was over and the people returned to their camps.

The twilight was fast passing away and night gradually spreading its darkness, like a pall, over the earth, when a beautiful full moon appeared with silvery radiance, to enlighten the whole country. Hark! the tom-tom is again sounding and all the men quickly arising don their blankets; the squaws huddle their smaller children on their neck and, driving the balance of their little ones before them, following one another in a long line, return to the play ground to assist at a great war dance.

"The small fire the kettle-tender had enkindled in the morning in the center of the arena is now turned by the same into a big bonfire."

"The small fire the kettle-tender had enkindled in the morning in the center of the arena is now turned by the same into a big bonfire."

The small fire the kettle-tender had enkindled in the morning in the center of the arena is now turned by the same into a big bonfire. Everyone is on the tip-toe watching who will be the Braves that will form the dance. And, behold, presently some twenty stalwart savages, each a well known old warrior, step out from different points and at once form a large circle around the fire. Some of them have horns protruding from their headgear; others are covered with loose buffalo robes dragging long tails; most have their faces covered with the mask of some wild animal; all exhibit the appearance of incarnate demons. Their bodies are daubed with large spots of white, red. green and yellow paint. They are armed with long spears from which are hanging the scalps of their enemies. And now their dance begins with a general whoop. They all start leaping and gesticulating like infernal furies around the big bon-fire. Their motions seem to be threatening everybody; their dance, properly speaking, is no dance at all, but rather a war drilling in which they feign to attack or strike their enemies in thousands of different ways. This very wild play lasted till late in the night, when the men got so exhausted by their continual jumping and stamping the ground that they had to give up and lie down to rest on the very spot. With this the whole feast was over.

On the next morning Lucille and Angelica resumed their ordinary excursions after flowers and, taught by their own experience, are more cautious in their ramblings.

On the next morning Lucille and Angelica resumed their ordinary excursions after flowers and, taught by their own experience, are more cautious in their ramblings.

Some Reference Information.