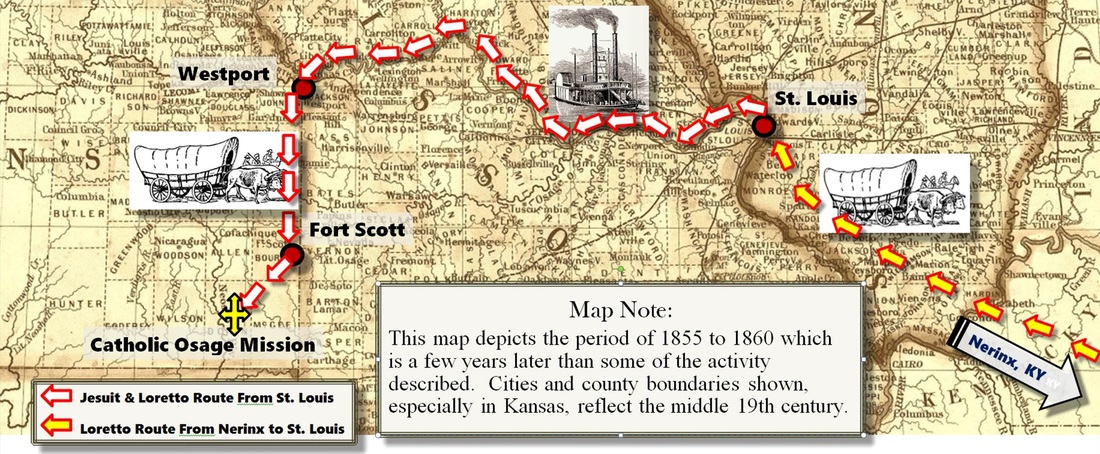

See full map below

5. The Catholic Osage Mission

“It would be impossible to paint for you the enthusiasm with which we were received … At first sight of these savages … I could not suppress the pain I felt … The adults had only a slight covering over the middle of the body; the little children, even as old as six or seven years, were wholly destitute of clothing. Half serious, half jesting, I thought that a truly savage portion of the Lord’s vineyard had been given to me to cultivate.”

— Father John Bax letter to Father Pierre Jean de Smet June 1, 1850

5. The Catholic Osage Mission

“It would be impossible to paint for you the enthusiasm with which we were received … At first sight of these savages … I could not suppress the pain I felt … The adults had only a slight covering over the middle of the body; the little children, even as old as six or seven years, were wholly destitute of clothing. Half serious, half jesting, I thought that a truly savage portion of the Lord’s vineyard had been given to me to cultivate.”

— Father John Bax letter to Father Pierre Jean de Smet June 1, 1850

The Osage petitioned the government to send the Jesuit “Black Robes” to teach their children. Their relationship with the French over several years had left a favorable impression. They had observed the respect the French displayed toward the priests and the respect seemed mutual. But getting the government to agree wasn’t going to be easy.

The government had already invested heavily in the Presbyterian Missions in Missouri, Oklahoma and southern Kansas. All failed over a period of seventeen years. Officials were not motivated to spend more money and effort on what was likely to be another failure. However, a new and enthusiastic Superintendent, Major Thomas H. Harvey, having received a new petition in May of 1844, managed to convince the government to rethink a Catholic Mission. In July of 1844 President Tyler decided to try a Catholic Osage Mission on an experimental basis. Now the problem was finding Catholic missionaries and selecting a location.

The government had already invested heavily in the Presbyterian Missions in Missouri, Oklahoma and southern Kansas. All failed over a period of seventeen years. Officials were not motivated to spend more money and effort on what was likely to be another failure. However, a new and enthusiastic Superintendent, Major Thomas H. Harvey, having received a new petition in May of 1844, managed to convince the government to rethink a Catholic Mission. In July of 1844 President Tyler decided to try a Catholic Osage Mission on an experimental basis. Now the problem was finding Catholic missionaries and selecting a location.

Father John Schoenmakers

Father John Schoenmakers

A Site Survey of the Mission - 1846.

It took nearly three years to complete arrangements, the complexity of which is beyond the scope of this segment (See Reference Information below). So we’ll fast-forward to the fall of 1846 when thirty-nine year-old Father John Schoenmakers visited a primitive location thirty miles west of Missouri border with the frontier desert. He was here to do a site inspection of what became his home. The purpose of the inspection was to ascertain what equipment and supplies would be needed, by himself and a missionary team, to start and sustain the Mission. He also wanted to introduce himself to the Osages.

What he found at the site was disturbing. The buildings were not yet completed and the contractors were uncomfortable with the remote location. They were among very few whites in the region and they wanted to get back to civilization. Supplies and equipment were scarce, and they had cut many corners. The poor quality of their work would become evident when the Mission was occupied. His meetings with the Osages were a mixed blessing. He was very warmly welcomed by the chiefs and their people; but then he fully comprehended the term “savage” as it was used to describe his new flock. Father Schoenmakers had been briefed in Missouri on what to expect, but he was unprepared for what he observed. Nonetheless he returned to St. Louis and began assembling his missionary team and supplies.

It took nearly three years to complete arrangements, the complexity of which is beyond the scope of this segment (See Reference Information below). So we’ll fast-forward to the fall of 1846 when thirty-nine year-old Father John Schoenmakers visited a primitive location thirty miles west of Missouri border with the frontier desert. He was here to do a site inspection of what became his home. The purpose of the inspection was to ascertain what equipment and supplies would be needed, by himself and a missionary team, to start and sustain the Mission. He also wanted to introduce himself to the Osages.

What he found at the site was disturbing. The buildings were not yet completed and the contractors were uncomfortable with the remote location. They were among very few whites in the region and they wanted to get back to civilization. Supplies and equipment were scarce, and they had cut many corners. The poor quality of their work would become evident when the Mission was occupied. His meetings with the Osages were a mixed blessing. He was very warmly welcomed by the chiefs and their people; but then he fully comprehended the term “savage” as it was used to describe his new flock. Father Schoenmakers had been briefed in Missouri on what to expect, but he was unprepared for what he observed. Nonetheless he returned to St. Louis and began assembling his missionary team and supplies.

Arrival of the Black Robes.

On April 28, 1847 a small procession of ox-drawn wagons rolled into the grounds of the Catholic Osage Mission. Five men climbed down from the carts and were quickly surrounded by an enthusiastic group of Osage who had come to greet the Tapuska-Watanka (priest lords). The missionaries included Father Schoenmakers and his young assistant Father John Bax; and three coadjutor brothers: John Sheehan, John De Bruyn and Thomas Coglan (Brother Thomas O’Donnell joined them in 1848). All five of the men had already immigrated to a new land when they came to America. But the Mission site might have seemed alien. Father Bax’s impression of their arrival is embodied in the opening quote.

The team of Jesuits was travel-weary. They had left St. Louis on April 7 via river steamer and the voyage down the Missouri River took nearly a week. When they arrived at Westport their possessions and supplies were transferred to wagons for the rough, dusty prairie leg that took nearly two weeks. Fatigue might have been bolstered by the excitement of their new flock of Osage. They unloaded the wagons, set up their classrooms and opened the Osage Manual Labor School for Boys on May 10, 1847. By the end of the month fourteen Indians and mixed-bloods had enrolled—at the end of two months it was eighteen.

On April 28, 1847 a small procession of ox-drawn wagons rolled into the grounds of the Catholic Osage Mission. Five men climbed down from the carts and were quickly surrounded by an enthusiastic group of Osage who had come to greet the Tapuska-Watanka (priest lords). The missionaries included Father Schoenmakers and his young assistant Father John Bax; and three coadjutor brothers: John Sheehan, John De Bruyn and Thomas Coglan (Brother Thomas O’Donnell joined them in 1848). All five of the men had already immigrated to a new land when they came to America. But the Mission site might have seemed alien. Father Bax’s impression of their arrival is embodied in the opening quote.

The team of Jesuits was travel-weary. They had left St. Louis on April 7 via river steamer and the voyage down the Missouri River took nearly a week. When they arrived at Westport their possessions and supplies were transferred to wagons for the rough, dusty prairie leg that took nearly two weeks. Fatigue might have been bolstered by the excitement of their new flock of Osage. They unloaded the wagons, set up their classrooms and opened the Osage Manual Labor School for Boys on May 10, 1847. By the end of the month fourteen Indians and mixed-bloods had enrolled—at the end of two months it was eighteen.

A stylized drawing of the Loretto at the Foot of the Cross Convent at Nerinx. Kentucky. The drawing is believed to have been done in Belgium from descriptions; which might explain the mountains and palm trees. A colorized version is shown in Mother Hayden's segment.

A stylized drawing of the Loretto at the Foot of the Cross Convent at Nerinx. Kentucky. The drawing is believed to have been done in Belgium from descriptions; which might explain the mountains and palm trees. A colorized version is shown in Mother Hayden's segment.

Staffing the Girl’s School.

The opening phase was complete but Father Schoenmakers’ contract with the government included educating Osage boys and girls. So he set about the difficult task of finding a group of religious women to run his girl’s school. In St. Louis he talked to several orders of nuns. None were willing to face the rigors and danger of the isolated prairie assignment. Discouraged, he traveled to Kentucky to visit the Loretto Mother House in Nerinx. The Sisters of Loretto were receptive. Their ranks included sophisticated, well-educated young women who had vowed to serve the missionary works of God. On October 10, 1847, Father Schoenmakers returned to the Mission with Mother Concordia Henning and Sisters Bridget Hayden, Mary Petronilla van Prater and Vincentia McCool. The Osage School for Girls opened on the day of their arrival.

Now, the Mission was functioning precariously. The nine Jesuit and Loretto missionaries were among few white people in the region and all but one of them were immigrants. Kansas was not yet a territory and statehood was fourteen years in the future. The only semblance of law and authority was Fort Scott, nearly forty miles away. As time passed, Father Schoenmakers became a regional point of authority.

The time ahead of the missionary team would be both rewarding and frightening.

The opening phase was complete but Father Schoenmakers’ contract with the government included educating Osage boys and girls. So he set about the difficult task of finding a group of religious women to run his girl’s school. In St. Louis he talked to several orders of nuns. None were willing to face the rigors and danger of the isolated prairie assignment. Discouraged, he traveled to Kentucky to visit the Loretto Mother House in Nerinx. The Sisters of Loretto were receptive. Their ranks included sophisticated, well-educated young women who had vowed to serve the missionary works of God. On October 10, 1847, Father Schoenmakers returned to the Mission with Mother Concordia Henning and Sisters Bridget Hayden, Mary Petronilla van Prater and Vincentia McCool. The Osage School for Girls opened on the day of their arrival.

Now, the Mission was functioning precariously. The nine Jesuit and Loretto missionaries were among few white people in the region and all but one of them were immigrants. Kansas was not yet a territory and statehood was fourteen years in the future. The only semblance of law and authority was Fort Scott, nearly forty miles away. As time passed, Father Schoenmakers became a regional point of authority.

The time ahead of the missionary team would be both rewarding and frightening.

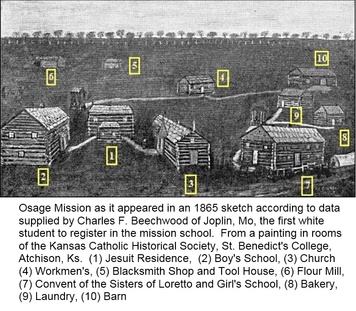

The Layout of the Catholic Mission.

When completed the Catholic Mission complex included ten buildings. The major buildings were the church, two school buildings, and a Jesuit residence. The mission also included several other maintenance and utility buildings needed to sustain the schools at a very remote location. Follow these links (or "Story" sub-links) to three pages that will describe:

When completed the Catholic Mission complex included ten buildings. The major buildings were the church, two school buildings, and a Jesuit residence. The mission also included several other maintenance and utility buildings needed to sustain the schools at a very remote location. Follow these links (or "Story" sub-links) to three pages that will describe:

- 5A - The Mission Complex

- 5B - The Osage Mission Manual Labor Schools

- 5C - A Beacon on the Plains (the first church)

- 5D - It Didn't Happen Here. The Osage Mission Missionary Priests and Sisters Did Not Abuse the Osage.

Go to: 6. The Early Days - Progress and Tragedy - or - Story

Some Reference Information:

*Note: Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald’s “Beacon on the Plains” provides many of the details regarding approval of the Catholic Osage Mission as well as the wording of the actual contract between the government and the Jesuits. The book is available at the Graves Memorial Public Library or may be purchased from the Osage Mission – Neosho County Historical Society.

- Father Bax’s opening quote was part of a letter he wrote to Jesuit Missionary explorer Father Pierre Jean de Smet. That letter is included in this page from the Sequoia Research Center’s archives. http://www.ualr.edu/sequoyah/uploads/2011/11/The%20Osage%20--%20A%20Historical%20Sketch.htm

- Beacon on the Plains, Sister Paul Mary Fitzgerald, 1939*

- Father John Schoenmakers, Apostle to the Osages, W.W. Graves, 1928

- Life and Times of Mother Bridget, W.W. Graves, 1938

- Father Schoenmakers Photograph – Osage Mission, Neosho County Historical Society (Original Source Likely the Jesuit Archives)

- The drawing of the Loretto at the Foot of the Cross is available at several web sources. A colorized version is available at: Kentucky Online Resources Blog, https://kentuckyonlinearts.wordpress.com/category/kentucky-history/

*Note: Sister Mary Paul Fitzgerald’s “Beacon on the Plains” provides many of the details regarding approval of the Catholic Osage Mission as well as the wording of the actual contract between the government and the Jesuits. The book is available at the Graves Memorial Public Library or may be purchased from the Osage Mission – Neosho County Historical Society.