14. Citizen Lawmen - The Anti-Horse Thief Association.

“If Maj. David McKee gave birth to and raised the Anti-Horse Thief Association it was W.W. Graves who brought into adulthood.”

— From Bullets, Badges and Bridles, by John K. Burchill. 2014

“If Maj. David McKee gave birth to and raised the Anti-Horse Thief Association it was W.W. Graves who brought into adulthood.”

— From Bullets, Badges and Bridles, by John K. Burchill. 2014

When John Burchill contacted our local museum in 2011 he was in a dilemma. John, a Kansas Wesleyan University professor, was writing a book about early American vigilance groups. He knew the Anti-Horse Thief Association (A.H.T.A) was organized in northeastern Missouri; but most of his research material led him to St. Paul, Kansas. He dug out an atlas to find St. Paul, and then called. After spending a day here at the museum he went home with a much better understanding of the association’s heyday—much of their later success was managed from right here in St. Paul, Kansas. (See Notes 1 and 2 at the bottom of this page).

Sources conflict with regard to location of the first founding meeting of the A.H.T.A.. W. W. Graves credits Athens, MO but members from both Athens and Luray were very involved.

Sources conflict with regard to location of the first founding meeting of the A.H.T.A.. W. W. Graves credits Athens, MO but members from both Athens and Luray were very involved.

Missouri Origin of the A.H.T.A.

During the middle of the 19th century horse theft was a serious problem. Settlers and small farmers did not have insurance and the loss of horses or farm stock imposed serious financial stress. In rural areas law enforcement officers were scarce and they were hampered by local judiciary boundaries. Add to this the increasing tension and lawlessness in the period leading to the Civil War and the theft of individual, or herds of, horses reached critical proportions. Horse theft was easy and lucrative.

Thievery was a particular problem in extreme northeast Missouri. Clark County bordered with both Iowa and Illinois. Stolen horses were quickly shuttled across the Mississippi or Illinois Rivers, or a strip of Iowa state line and they were out of state. Local authorities had to deal with three local jurisdictions and the cost to apprehend and extradite became prohibitive. Horses were seldom recovered or local posse’s often settled matters with guns and a rope.

During the middle of the 19th century horse theft was a serious problem. Settlers and small farmers did not have insurance and the loss of horses or farm stock imposed serious financial stress. In rural areas law enforcement officers were scarce and they were hampered by local judiciary boundaries. Add to this the increasing tension and lawlessness in the period leading to the Civil War and the theft of individual, or herds of, horses reached critical proportions. Horse theft was easy and lucrative.

Thievery was a particular problem in extreme northeast Missouri. Clark County bordered with both Iowa and Illinois. Stolen horses were quickly shuttled across the Mississippi or Illinois Rivers, or a strip of Iowa state line and they were out of state. Local authorities had to deal with three local jurisdictions and the cost to apprehend and extradite became prohibitive. Horses were seldom recovered or local posse’s often settled matters with guns and a rope.

Major David McKee is credited with leading the initial start of the association in 1854 and the formal founding of the A.H.T.A. in 1863

Major David McKee is credited with leading the initial start of the association in 1854 and the formal founding of the A.H.T.A. in 1863

In the autumn of 1854 Major David McKee and a small group of men decided to take action. They met at the Highland School House in Clark County, near the Iowa state line. They formed a lodge called the Anti-Horse Thief Association and McKee’s friend Hugh Allen Stewart was the lodge treasurer. A few loosely formed chapters were established but some groups had issues with the “secret” nature of the association. Plans to form a viable vigilance network were thwarted by the outbreak of the Civil War when many of the organizers were called to service. The war delayed a formal founding of the association; but it also intensified its need. Rogue militants became more reckless and desperate, especially with stealing horses and farm livestock.

After McKee’s return from service, the national order of the A.H.T.A. was created on October 23, 1863. There is some disagreement as to whether the founding meeting was in Luray or Athens, Missouri, but W.W. Graves credits Athens with this meeting; and Luray with a pre-war formative gathering. It probably doesn’t matter because the intent to take action is firmly rooted in Clark County. The October, 1863, date is considered to be the founding date of the Anti-Horse Thief Association.

After McKee’s return from service, the national order of the A.H.T.A. was created on October 23, 1863. There is some disagreement as to whether the founding meeting was in Luray or Athens, Missouri, but W.W. Graves credits Athens with this meeting; and Luray with a pre-war formative gathering. It probably doesn’t matter because the intent to take action is firmly rooted in Clark County. The October, 1863, date is considered to be the founding date of the Anti-Horse Thief Association.

Steady Growth Through the End of the 19th Century.

After its second start, the A.H.T.A. began a steady growth that extended well beyond Missouri. The growth was caused by need; but more importantly by the organization’s reputation for sound planning and execution. The foremost principle of the new association was it was not a vigilante group that was, by definition, usually outlaw in itself. The association was formed to supplement the existing resources of law enforcement with groups of armed, trained men that could be dispatched quickly. Perhaps the most important aspect of the association was that a group of “Antis” were not encumbered by legal jurisdiction. It was lightly boasted that an A.H.T.A. posse would ‘chase a thief to the gates of hell—and go on in if needed.’ The main limitation was the ability of their horses to hold up to the chase. Their objective was always deliverance of the criminal to the hands of the local sheriff. It should also be noted that between the original gathering in 1854 and its official founding in 1863, many of its members had been transformed from angry, frustrated farmers to combat hardened veterans. They were a formidable force against crime.

After its second start, the A.H.T.A. began a steady growth that extended well beyond Missouri. The growth was caused by need; but more importantly by the organization’s reputation for sound planning and execution. The foremost principle of the new association was it was not a vigilante group that was, by definition, usually outlaw in itself. The association was formed to supplement the existing resources of law enforcement with groups of armed, trained men that could be dispatched quickly. Perhaps the most important aspect of the association was that a group of “Antis” were not encumbered by legal jurisdiction. It was lightly boasted that an A.H.T.A. posse would ‘chase a thief to the gates of hell—and go on in if needed.’ The main limitation was the ability of their horses to hold up to the chase. Their objective was always deliverance of the criminal to the hands of the local sheriff. It should also be noted that between the original gathering in 1854 and its official founding in 1863, many of its members had been transformed from angry, frustrated farmers to combat hardened veterans. They were a formidable force against crime.

Principles of Operation.

As the A.H.T.A. grew its organizers required that certain standards be applied to all chapters. Regional chapters were given leeway to tailor some practices but in general, the following standards were met at all locations:

As the A.H.T.A. grew its organizers required that certain standards be applied to all chapters. Regional chapters were given leeway to tailor some practices but in general, the following standards were met at all locations:

- Membership – Any reputable citizen over eighteen years of age was eligible to join. Women could apply as Protective Members but were not expected nor allowed to participate in pursuits. Widows of deceased members were given the same protection as if her husband had lived.

- Dues – A structure of membership and lodge fees was established. This revenue was used to fund lodge operations, pursuits and administration costs.

- There were no salaried positions in the A.H.T.A. Everything was done on a voluntary basis and expenses were paid from fees.

- Members served members first and foremost; and potential criminals knew if they wronged a single member of the A.H.T.A. they would have to deal with the long arms of the association.

- If a member was chosen to pursue a thief he was expected to participate. Absence of a credible excuse was subject to $5 fine. If you did participate all expenses were paid.

- The association also served non-members, but expected reimbursement if they were successful.

- “Wild Goose (or horse) Chases” were not appreciated. If a member energized a posse pursuit, and then discovered his stock had wandered off, he paid expenses for the pursuit.

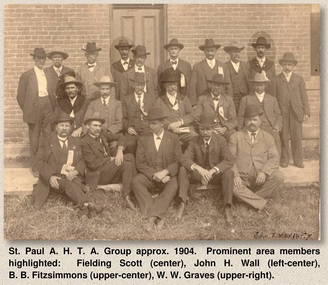

St. Paul farmer and businessman Fielding Scott played a prominent role in the association's rapid early 20th century growth.

St. Paul farmer and businessman Fielding Scott played a prominent role in the association's rapid early 20th century growth.

The Southeast Kansas Influence Steps Up.

The first known A.H.T.A. activity in Neosho County, Kansas was formation of Sub order No. 177 in Ladore Township in 1880 or 1881. This unit preceded the Kansas State order that was formed in 1881. The organization steadily gained ground as the county added three more sub orders before hosting a national convention, in Chanute, in 1891. Sub orders also began to appear across eastern Kansas areas including Pittsburg and Emporia. By the end of the century the area of eastern Kansas and northeast Oklahoma was becoming an A.H.T.A. hot-spot.

In 1899 Fielding Scott, of St. Paul, Kansas, was elected as vice-president of the national order. That election marked the beginning of events that would put St. Paul at the center of A.H.T.A. national influence for three decades. In 1900 Scott was instrumental in getting that year’s national convention into Chanute where he was elected national president. He served subsequent terms in the national position in 1901, 1902 and 1903. During his reign he directed several changes that resulted in explosive growth in memberships and national prominence.

The first known A.H.T.A. activity in Neosho County, Kansas was formation of Sub order No. 177 in Ladore Township in 1880 or 1881. This unit preceded the Kansas State order that was formed in 1881. The organization steadily gained ground as the county added three more sub orders before hosting a national convention, in Chanute, in 1891. Sub orders also began to appear across eastern Kansas areas including Pittsburg and Emporia. By the end of the century the area of eastern Kansas and northeast Oklahoma was becoming an A.H.T.A. hot-spot.

In 1899 Fielding Scott, of St. Paul, Kansas, was elected as vice-president of the national order. That election marked the beginning of events that would put St. Paul at the center of A.H.T.A. national influence for three decades. In 1900 Scott was instrumental in getting that year’s national convention into Chanute where he was elected national president. He served subsequent terms in the national position in 1901, 1902 and 1903. During his reign he directed several changes that resulted in explosive growth in memberships and national prominence.

B.B Fitzsimmons assisted W. W. Graves in acquiring the St. Paul Journal and securing the A.H.T.A. Weekly contract.

B.B Fitzsimmons assisted W. W. Graves in acquiring the St. Paul Journal and securing the A.H.T.A. Weekly contract.

Other Neosho County residents rose to state and national prominence. Among them were John W. Wall of Ladore and B.B. Fitzsimmons, St. Paul. In 1901 Wall and Scott devised a plan to start a weekly A.H.T.A. newspaper to provide a common communication link across widely-distribute sub orders. It would also be used to recruit new interest in the organization. John Wall chaired the committee that authorized the paper. In late 1901 he distributed requests for proposals to several publishers.

Fitzsimmons was a close friend of young, upstart newspaperman William Whites Graves. He and his father helped Graves acquire the St. Paul Journal a few years earlier. He knew young Graves was well-educated and full of ambition. Fitzsimmons and Scott encouraged Graves to submit a bid for the contract. While young Graves was ambitious; his tiny upstairs printing operation, on St. Paul’s main street, was pitifully inadequate. Nonetheless, Bill Graves put together a compelling proposal and won the contract.

Fitzsimmons was a close friend of young, upstart newspaperman William Whites Graves. He and his father helped Graves acquire the St. Paul Journal a few years earlier. He knew young Graves was well-educated and full of ambition. Fitzsimmons and Scott encouraged Graves to submit a bid for the contract. While young Graves was ambitious; his tiny upstairs printing operation, on St. Paul’s main street, was pitifully inadequate. Nonetheless, Bill Graves put together a compelling proposal and won the contract.

W. W. Graves gained considerable influence with the A.H.T.A.

W. W. Graves gained considerable influence with the A.H.T.A.

I have found no evidence that W.W. Graves was active in, or even a member of, the Anti-Horse Thief Association before 1901. But the award of the A.H.T.A. Weekly contract was a game-changer for both Graves and the association. For Graves, it provided the revenue to quickly acquire a new building and begin capital improvement projects that spanned several years. By 1912 The Journal Publishing Company was a state-of-art publishing plant capable of handling more local and state newspapers and magazines. For a time, Graves' shop printed the Kansas State Knights of Columbus newspaper which was as much magazine as newspaper. It could also print books and brochures—and book publishing became very important to Graves who was also a historian. As business increased Graves' brother-in-law and partner, A. J. Hopkins became active in the association and assumed much of the work related to publishing and distributing the A.H.T.A. Weekly newspaper.

A short-term effect of bringing Graves into the organization was recruiting. Armed with the newspaper, and its persuasive young publisher, Scott was able to quickly effect two important consolidations:

1. In August of 1902 Scott and Graves traveled to Siloam Springs, Arkansas to meet with local members of the Independent Order of the Knights of the Horse. The I.O.K.H., established in 1884, had similar goals and principles as the A.H.T.A. and Scott had been in correspondence with leaders for some time. They were so impressed with the Scott-Graves presentation it took little effort to convince the Arkansas organization to join their ranks.

2. A year later, in August of 1903, the duo traveled to Joplin to promote the transfer of the Southwest Missouri Protective Association into the A.H.T.A. The S.M.P.A., which was chartered in May of 1890, was also similar to the A.H.T.A. and the consolidation was successful.

At age 32, the small-town newspaperman was gaining some prominence with a well-established national vigilance organization. Bill Graves had a strong mentor in Fielding Scott and would work and travel with him for some time. But Graves had some ideas of his own.

A short-term effect of bringing Graves into the organization was recruiting. Armed with the newspaper, and its persuasive young publisher, Scott was able to quickly effect two important consolidations:

1. In August of 1902 Scott and Graves traveled to Siloam Springs, Arkansas to meet with local members of the Independent Order of the Knights of the Horse. The I.O.K.H., established in 1884, had similar goals and principles as the A.H.T.A. and Scott had been in correspondence with leaders for some time. They were so impressed with the Scott-Graves presentation it took little effort to convince the Arkansas organization to join their ranks.

2. A year later, in August of 1903, the duo traveled to Joplin to promote the transfer of the Southwest Missouri Protective Association into the A.H.T.A. The S.M.P.A., which was chartered in May of 1890, was also similar to the A.H.T.A. and the consolidation was successful.

At age 32, the small-town newspaperman was gaining some prominence with a well-established national vigilance organization. Bill Graves had a strong mentor in Fielding Scott and would work and travel with him for some time. But Graves had some ideas of his own.

A Young Businessman’s Perspective of the Vigilance Group.

The A.H.T.A. had a brilliant young businessman at the center of their national communications. In addition to the Weekly contract, Graves had his hands in several other local businesses and he knew how to manage. He quickly learned about the association’s operations and recognized weaknesses. Over the period of ten to twelve years he assisted state orders with publishing their local constitutions and in doing so established commonality among states. He also recruited judges and attorneys to assist with development of pocket-sized guidebooks for posse members. W.W. Graves’ pamphlet “Law for Criminal Catchers” reads like a modern-day manual describing the rights of posse members as well as those they were apprehending. It also laid standard guidelines for arrests, collection of evidence, and follow up expectations after arrests were completed. This publication gained acceptance by professional peace officers as well as members of the association.

The A.H.T.A. had a brilliant young businessman at the center of their national communications. In addition to the Weekly contract, Graves had his hands in several other local businesses and he knew how to manage. He quickly learned about the association’s operations and recognized weaknesses. Over the period of ten to twelve years he assisted state orders with publishing their local constitutions and in doing so established commonality among states. He also recruited judges and attorneys to assist with development of pocket-sized guidebooks for posse members. W.W. Graves’ pamphlet “Law for Criminal Catchers” reads like a modern-day manual describing the rights of posse members as well as those they were apprehending. It also laid standard guidelines for arrests, collection of evidence, and follow up expectations after arrests were completed. This publication gained acceptance by professional peace officers as well as members of the association.

Emblems and belt fobs were popular with members. Graves designed and distributed several articles like these.

Emblems and belt fobs were popular with members. Graves designed and distributed several articles like these.

Graves also recognized business potential for himself. In addition to publications like “Law for Criminal Catchers”, he also designed and printed standard forms and publications for the orders and sub orders. He provided what he called “a set of handy record books for the local officers” and he sold several hundred of them. His compact book “Tricks of Rascals” was self-described as a “breezy pamphlet that explained the methods employed by crooks to get other people’s money.” Some of the scoundrel-antics described in this book remind me of modern-day plots and plans, including some internet scams. Graves sold 3,000 copies of it to members and lawmen. He also designed and arranged the manufacture of small emblem pins and sold thousands. Journal Publishing sold thousands of inexpensive A.H.T.A. horseshoe emblems that were nailed to gate posts or barn doors to warn scoundrels they might want to think twice about stealing from an A.H.T.A. member. These emblems later adorned the grilles of automobiles driven by members. While I cannot prove it, I suspect Graves also had a hand in distributing thousands of pewter and blue belt fobs worn by men well into the 1960’s and 70’s.

Local members who were largely responsible for the association's growth. (click to enlarge)

Local members who were largely responsible for the association's growth. (click to enlarge)

But make no mistake, while Graves profited from his work with the A.H.T.A., the association was part of his heart and soul. As you scan microfilm of the St. Paul Journal, many copies between 1902 and the early 30’s include stories or accolades about the association. During his tenure with the A.H.T.A. Weekly, he claimed he never missed a national convention; and this was during a period when travel was more problematic than it is now. During the period of 1902 to 1916 A.H.T.A. membership grew from about 8,000 members to at least 40,000 members—some sources say 50,000 members, with nearly ½ in Kansas. Perhaps more important, the range of influence, from a small publishing plant on Main Street of St. Paul, reached at least nineteen states (below). That influence also boosted the A.H.T.A. to a high level of national respect and the man doing much of the work had not yet served in a national office.

A.H.T.A Range of Influence. (click to enlarge)

A.H.T.A Range of Influence. (click to enlarge)

Sunset.

Graves did finally serve two terms each as national vice president and president (1922-1925). By then the A.H.T.A. had progressed to modern crime fighting including auto theft, fraud, assaults and murders. Members were well-trained and prepared to support prosecutors. The association had become legendary, sometimes called to service by the Brinks Detective Agency. Some say that the A.H.T.A. was more effective than Brinks because they worked for their members, not a paycheck. But by the time William Whites Graves served his national terms his association was in decline. John Burchill includes the lack of manpower during World War I; and infiltration by the Ku Klux Klan as being detrimental factors. On a larger scale I cannot disagree with John’s assessment; but I do not believe Graves would have had patience with the Klan. He was a devout Catholic and he was not shy. Nevertheless, in May of 1932 Graves sold his beloved A.H.T.A. Weekly News contract to Hugh Gresham of Cheney, Kansas and stepped away from active service.

The association and the newspaper underwent name changes in an attempt to maintain relevance—the attempts were unsuccessful. At the end of their era they simply lost purpose. The Anti-Horse Thief Association was formed to fill the gap among sparsely available law enforcement officials. As the frontier era progressed into the early 20th century, law enforcement progressed with it. State and national programs matured and so did communications. By the late 1930’s the Antis had done their job and could very proudly ride off into the sunset.

Graves did finally serve two terms each as national vice president and president (1922-1925). By then the A.H.T.A. had progressed to modern crime fighting including auto theft, fraud, assaults and murders. Members were well-trained and prepared to support prosecutors. The association had become legendary, sometimes called to service by the Brinks Detective Agency. Some say that the A.H.T.A. was more effective than Brinks because they worked for their members, not a paycheck. But by the time William Whites Graves served his national terms his association was in decline. John Burchill includes the lack of manpower during World War I; and infiltration by the Ku Klux Klan as being detrimental factors. On a larger scale I cannot disagree with John’s assessment; but I do not believe Graves would have had patience with the Klan. He was a devout Catholic and he was not shy. Nevertheless, in May of 1932 Graves sold his beloved A.H.T.A. Weekly News contract to Hugh Gresham of Cheney, Kansas and stepped away from active service.

The association and the newspaper underwent name changes in an attempt to maintain relevance—the attempts were unsuccessful. At the end of their era they simply lost purpose. The Anti-Horse Thief Association was formed to fill the gap among sparsely available law enforcement officials. As the frontier era progressed into the early 20th century, law enforcement progressed with it. State and national programs matured and so did communications. By the late 1930’s the Antis had done their job and could very proudly ride off into the sunset.

Notes:

- It is important to distinguish between vigilante and vigilance groups. “Vigilante” groups are self-appointed groups of citizens who undertake law enforcement without legal authority. Their actions often end in violence and by definition they are outlaw groups. Vigilance groups, by contrast, work within the law and in cooperation with local law enforcement organizations.

- John Burchill’s book, Bullets, Badges and Bridles was published in 2014. His section about the A.H.T.A includes discussion about the local role in bringing the association to maturity. Part of his manuscript and his source material was checked locally. The book is available through many booksellers and internet sources.

Go to: 15. The Passionist Influence is Expanded - or - Story

Go to: A brief photo-article about the 1914 meeting of the Kansas A.H.T.A. in Chanute.

Go to: A brief photo-article about the 1914 meeting of the Kansas A.H.T.A. in Chanute.

Some Reference Information:

Much of the information for this segment was compiled during a research project for the Graves Memorial Public Library in St. Paul. The project included development of a set of five display panels on the life and times of W. W. Graves. Panel #4 or five is about the A.H.T.A..

Much of the information for this segment was compiled during a research project for the Graves Memorial Public Library in St. Paul. The project included development of a set of five display panels on the life and times of W. W. Graves. Panel #4 or five is about the A.H.T.A..

- Bullets, Badges and Bridles – Horse Thieves and the Societies That Pursued Them, John K. Burchill, 2014

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, The Anti-Horse Thief Association. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/A/AN012.htm

- History of Neosho County, Volume II, W.W. Graves, 1951

- Making Money With a Country Newspaper, W.W. Graves, 1916

- Origins and Principles of the Anti-Horse Thief Association, W.W. Graves, 1914

- The Long Riders Guild Academic Foundation, The Anti-Horse Thief Association, http://www.lrgaf.org/articles/ahta.htm

- The header photo was scanned from the cover of Bullets, Badges and Bridles. Used with permission of the author John Burchill.

- The map of northeastern Missouri was taken from 1858 map of Indiana, Illinois, Missouri & Iowa; Library of Congress. It has been edited by me to add key towns and state names.

- The map of the United States showing A.H.T.A. involvement was photo-edited from a stock photo downloaded from the internet.

- The photo of Major David McKee - Major David McKee Collection, Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

- Images of B. B. Fitzsimmons and Fielding Scott were scanned from History of Neosho County, Volume II, W. W. Graves, 1951.

- Image of W. W. Graves was scanned by me during archiving of the Graves - Hopkins Collection which is on file with the Osage Mission - Neosho County Historical Society.