9A. It Didn’t Happen Here.

The Osage Mission Priests and Sisters Did Not Abuse the Osage People. They supported and protected the Osage, and one of them gave his life.

The Osage Mission Priests and Sisters Did Not Abuse the Osage People. They supported and protected the Osage, and one of them gave his life.

We share information with history groups in Kansas and some national sites. With posts about the Osage Catholic Mission itself, we occasionally get comments about abuse of the Native Americans by Christian missionaries. The claims of abuse range from forced assimilation to white culture and customs, to all-out physical abuse and worse. Pope Francis recently made history when he apologized to the indigenous people of Canada for abuses suffered at Catholic residence schools. Now, the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota is re-investigating its past.

Abuse did happen at some locations. But abuse and forced assimilation of students and adults were not the norms — but isolated cases do tempt sensational newsprint. It is noted that the purpose of many of the missions was to help Native American students adapt to the white man’s world and customs. Civilization was coming and some tribal leaders knew their youngsters needed to be educated and exposed to the “European” ways. Some missions did a better job of preparing the students than others. Some failed outright.

Abuse did happen at some locations. But abuse and forced assimilation of students and adults were not the norms — but isolated cases do tempt sensational newsprint. It is noted that the purpose of many of the missions was to help Native American students adapt to the white man’s world and customs. Civilization was coming and some tribal leaders knew their youngsters needed to be educated and exposed to the “European” ways. Some missions did a better job of preparing the students than others. Some failed outright.

Voluntary Assimilation?

The Osages were among the first of the plains tribes to request mission schools. By the late 18th century, they had become familiar with the European ways through trading business with the French, Spanish, and English fur traders. Over time, relationships developed, even marriages. The Osages initially remained distant from the English and Spaniards — there were trust issues. However, the French gained their trust and the Osage and French, especially the Chouteau’s, became tight trading partners. The Osages also took notice of the French holy men or “Black Robes.” The Jesuit Priests seemed to treat the French, the Indians, and the area settlers with equal respect.

The Osages' experience with the Europeans also convinced tribal leaders that the white civilization was coming, and they would not be able to stop it. The whites were arriving from the east in large numbers, and they had the economic and military might to overcome tribal resistance. On the other hand, the government allowed the Osages some leeway because they were a formidable military and economic force. They had a reputation for being large in stature, fierce warriors when provoked, and also fairly shrewd traders and businessmen. These traits might have allowed them to negotiate their way into their Kansas and Oklahoma reserves, avoiding the brutal government relocations of the Cherokees, Potawatomi's, and others

The Osages were among the first of the plains tribes to request mission schools. By the late 18th century, they had become familiar with the European ways through trading business with the French, Spanish, and English fur traders. Over time, relationships developed, even marriages. The Osages initially remained distant from the English and Spaniards — there were trust issues. However, the French gained their trust and the Osage and French, especially the Chouteau’s, became tight trading partners. The Osages also took notice of the French holy men or “Black Robes.” The Jesuit Priests seemed to treat the French, the Indians, and the area settlers with equal respect.

The Osages' experience with the Europeans also convinced tribal leaders that the white civilization was coming, and they would not be able to stop it. The whites were arriving from the east in large numbers, and they had the economic and military might to overcome tribal resistance. On the other hand, the government allowed the Osages some leeway because they were a formidable military and economic force. They had a reputation for being large in stature, fierce warriors when provoked, and also fairly shrewd traders and businessmen. These traits might have allowed them to negotiate their way into their Kansas and Oklahoma reserves, avoiding the brutal government relocations of the Cherokees, Potawatomi's, and others

A Formal Request.

In September of 1819, a delegation of Claremore’s bands submitted a final request for mission educators and mission activity started the next year.

But the first missionaries were not Jesuits.

At that time many of the Osages were spread along the Neosho and Verdigris Rivers between Fort Gibson, Oklahoma, and southeast Kansas. There were also villages east of present Nevada, Missouri, in Bates and Vernon Counties, near Halley’s Bluff. But, other than a few isolated contacts with Jesuits, the earliest organized missions were run by eastern Protestant missionary organizations. The initial Protestant efforts were led by the United Foreign Missionary Society which later merged with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Much of the influence, and the missionary workforce, came from New York and Connecticut. Their ranks were controlled by the Presbyterians, Congregational, and Dutch Reformed Churches acting together; but the missions were generally called Presbyterian.

Between 1820 and 1837 the Presbyterians ran six missions along the Grand-Neosho River in Oklahoma and Kansas. There was also one mission, Harmony Mission, located in Bates County, Missouri. Three Kansas missions included Hopefield Mission #3 in present southern Labette County, Boudinot Mission west of present St. Paul, and Mission Neosho, located near present-day Shaw, Kansas. Mission Neosho, started in 1824, was the first school in Kansas.

The Presbyterians were well-organized and well-funded. But due to their northeastern roots, and the times, they were characteristically puritan. The strict nature of the missionaries made it difficult for them to relate to the Osages’ customs and practices such as polygamy, casual horse theft, minimal clothing during warm weather, and their fierce way of dealing with opposing tribes. The Osages had even less tolerance for the missionaries' insistence that they were to become farmers and abandon their tribal traditions. The Protestants approached these issues with the intent of expunging elements of the Osage culture, abandoning their Great Spirit Wah-Kon-Tah, and turning them into white people. This was a non-starter for the Osages. The local fur traders provided little support to the missionaries because an Osage who farmed was no longer a fur customer. Many of the problems between the Osage, the Presbyterians, and the traders came to a head at Mission Neosho and the Presbyterian missions were suspended in 1837. Follow This Link for more information about the earliest protestant missions.

The government was not pleased with the failure of these first missions, and it took ten years of requests and negotiations for them to try ‘an experiment with the Jesuits.

In September of 1819, a delegation of Claremore’s bands submitted a final request for mission educators and mission activity started the next year.

But the first missionaries were not Jesuits.

At that time many of the Osages were spread along the Neosho and Verdigris Rivers between Fort Gibson, Oklahoma, and southeast Kansas. There were also villages east of present Nevada, Missouri, in Bates and Vernon Counties, near Halley’s Bluff. But, other than a few isolated contacts with Jesuits, the earliest organized missions were run by eastern Protestant missionary organizations. The initial Protestant efforts were led by the United Foreign Missionary Society which later merged with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Much of the influence, and the missionary workforce, came from New York and Connecticut. Their ranks were controlled by the Presbyterians, Congregational, and Dutch Reformed Churches acting together; but the missions were generally called Presbyterian.

Between 1820 and 1837 the Presbyterians ran six missions along the Grand-Neosho River in Oklahoma and Kansas. There was also one mission, Harmony Mission, located in Bates County, Missouri. Three Kansas missions included Hopefield Mission #3 in present southern Labette County, Boudinot Mission west of present St. Paul, and Mission Neosho, located near present-day Shaw, Kansas. Mission Neosho, started in 1824, was the first school in Kansas.

The Presbyterians were well-organized and well-funded. But due to their northeastern roots, and the times, they were characteristically puritan. The strict nature of the missionaries made it difficult for them to relate to the Osages’ customs and practices such as polygamy, casual horse theft, minimal clothing during warm weather, and their fierce way of dealing with opposing tribes. The Osages had even less tolerance for the missionaries' insistence that they were to become farmers and abandon their tribal traditions. The Protestants approached these issues with the intent of expunging elements of the Osage culture, abandoning their Great Spirit Wah-Kon-Tah, and turning them into white people. This was a non-starter for the Osages. The local fur traders provided little support to the missionaries because an Osage who farmed was no longer a fur customer. Many of the problems between the Osage, the Presbyterians, and the traders came to a head at Mission Neosho and the Presbyterian missions were suspended in 1837. Follow This Link for more information about the earliest protestant missions.

The government was not pleased with the failure of these first missions, and it took ten years of requests and negotiations for them to try ‘an experiment with the Jesuits.

The Catholic Mission.

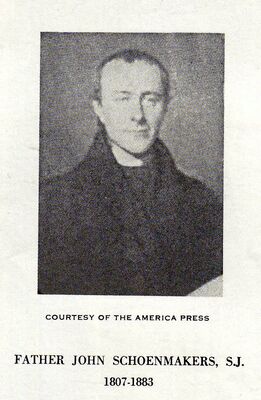

When Fathers Schoenmakers and Bax, and the first three Jesuit brothers arrived at the Catholic Mission in 1847, they were warmly received by the Osages. [1] They had been briefed on what to expect and Fr. Schoenmakers, in particular, had been trained at the De Neff School for Foreign Missionaries in Turnhout, Belgium. But there was no way they could have been ready for what was coming during the next 23 years.

The government buildings were inadequate and poorly built. Log chinking washed away and one of the fireplace chimneys collapsed. On a brighter note, enrollment at the Boy’s School grew fairly rapidly. When the Loretto’s arrived in October of 1847, the Girl's School started immediately. During its early years, the mission enjoyed good relationships with the government’s Osage agent, Major Andrew Dorn; and local fur traders, especially the Chouteau's. Dorn was considered to be the fairest and most effective of the government agents.

Success with converting the Osages to Christianity was mixed but Father Schoenmakers allowed leeway in blending their native rituals with the beliefs and rituals of the Catholic church. Wah-Kon-Tah was the Osage supreme being which could be related to the Catholic’s God. They had most of their success with the mixed-blood Canadian Osages who tenaciously clung to their Catholic faith, even if they didn't fully understand it. Father Schoenmakers remained patient.

The 1850s brought problems — Serious problems. From 1850 through 1856 a series of epidemics—scurvy, smallpox, and scrofula—took a terrible toll. In August of ’53 scurvy claimed the life of one of the Osages' most loved and trusted missionaries, Father John Bax. In dying, Father Bax demonstrated his total dedication to his flock of Osage children and adults. It appeared he simply worked himself to exhaustion, then the illness. The missionaries and Osages also had to deal with continuous rounds of drought, grasshopper plague, and crop failures. Then, came the Civil War.

In a speech on September 24 of 1870 Father Schoenmakers said “The war deprived the Osages of all their labor and prospects.” Boys at the school, above fifteen, joined the Union Army. Some of the Osages joined the Confederate Army, but most remained loyal to Schoenmakers and the Union. The mission was in constant danger of attack, but it was often the site of white-flag gatherings where both Union and Confederate soldiers sought food and medical help from the missionaries. But on a couple of occasions, our Osage Mission – St. Paul story came very close to ending violently.

By the end of the war, the Osage's future was sealed. Their numbers had diminished by disease and war. As they returned to their former hunting and camping grounds they were littered with the cabins of squatters. Pressure to release their Kansas reserve for settlement was mounting. In 1865 they signed the first of two treaties that ceded their south Kansas reserve. But they refused to sign that Treaty until the government agreed to one condition — Father Schoenmakers would be given one section of land, with options to buy more land at the price offered to settlers. This term was demanded by the Osages to show appreciation for the work he had done to educate and protect the Osages. The government balked at gifting land to a Catholic Priest, and the Osage planted their feet and refused to sign the treaty. Finally, after President Lincoln’s death, the government relented and accepted the Osages' terms. During negotiations of the second treaty Fr. Schoenmakers intervened to protect the tribe, and settlers, from the unscrupulous actions of the railroad robber barons. [2][3]

The Osage's appreciation was likely well deserved. In his book, A History of the Osage People, 1989, Osage historian Louis Burns said: “The Jesuits and Sisters of Osage Mission, probably more than any other outside factor, were responsible for the survival of the Osage people. It is no small wonder that eighty percent of the Osages are still Catholic today. These dedicated souls accomplished more than they lived to realize. Their Influence on the souls and aspirations of the Osage people is still present today.” [5]

When Fathers Schoenmakers and Bax, and the first three Jesuit brothers arrived at the Catholic Mission in 1847, they were warmly received by the Osages. [1] They had been briefed on what to expect and Fr. Schoenmakers, in particular, had been trained at the De Neff School for Foreign Missionaries in Turnhout, Belgium. But there was no way they could have been ready for what was coming during the next 23 years.

The government buildings were inadequate and poorly built. Log chinking washed away and one of the fireplace chimneys collapsed. On a brighter note, enrollment at the Boy’s School grew fairly rapidly. When the Loretto’s arrived in October of 1847, the Girl's School started immediately. During its early years, the mission enjoyed good relationships with the government’s Osage agent, Major Andrew Dorn; and local fur traders, especially the Chouteau's. Dorn was considered to be the fairest and most effective of the government agents.

Success with converting the Osages to Christianity was mixed but Father Schoenmakers allowed leeway in blending their native rituals with the beliefs and rituals of the Catholic church. Wah-Kon-Tah was the Osage supreme being which could be related to the Catholic’s God. They had most of their success with the mixed-blood Canadian Osages who tenaciously clung to their Catholic faith, even if they didn't fully understand it. Father Schoenmakers remained patient.

The 1850s brought problems — Serious problems. From 1850 through 1856 a series of epidemics—scurvy, smallpox, and scrofula—took a terrible toll. In August of ’53 scurvy claimed the life of one of the Osages' most loved and trusted missionaries, Father John Bax. In dying, Father Bax demonstrated his total dedication to his flock of Osage children and adults. It appeared he simply worked himself to exhaustion, then the illness. The missionaries and Osages also had to deal with continuous rounds of drought, grasshopper plague, and crop failures. Then, came the Civil War.

In a speech on September 24 of 1870 Father Schoenmakers said “The war deprived the Osages of all their labor and prospects.” Boys at the school, above fifteen, joined the Union Army. Some of the Osages joined the Confederate Army, but most remained loyal to Schoenmakers and the Union. The mission was in constant danger of attack, but it was often the site of white-flag gatherings where both Union and Confederate soldiers sought food and medical help from the missionaries. But on a couple of occasions, our Osage Mission – St. Paul story came very close to ending violently.

By the end of the war, the Osage's future was sealed. Their numbers had diminished by disease and war. As they returned to their former hunting and camping grounds they were littered with the cabins of squatters. Pressure to release their Kansas reserve for settlement was mounting. In 1865 they signed the first of two treaties that ceded their south Kansas reserve. But they refused to sign that Treaty until the government agreed to one condition — Father Schoenmakers would be given one section of land, with options to buy more land at the price offered to settlers. This term was demanded by the Osages to show appreciation for the work he had done to educate and protect the Osages. The government balked at gifting land to a Catholic Priest, and the Osage planted their feet and refused to sign the treaty. Finally, after President Lincoln’s death, the government relented and accepted the Osages' terms. During negotiations of the second treaty Fr. Schoenmakers intervened to protect the tribe, and settlers, from the unscrupulous actions of the railroad robber barons. [2][3]

The Osage's appreciation was likely well deserved. In his book, A History of the Osage People, 1989, Osage historian Louis Burns said: “The Jesuits and Sisters of Osage Mission, probably more than any other outside factor, were responsible for the survival of the Osage people. It is no small wonder that eighty percent of the Osages are still Catholic today. These dedicated souls accomplished more than they lived to realize. Their Influence on the souls and aspirations of the Osage people is still present today.” [5]

Shouminka Window at Immaculate Conception Catholic Church, Pawhuska. The "Cathedral of the Osage."

Shouminka Window at Immaculate Conception Catholic Church, Pawhuska. The "Cathedral of the Osage."

In addition to Burns’ words, the Osages have immortalized Father Schoenmakers in three ways:

- The Osage language word for priest is “Shouminka”— taken from Father Schoenmakers name.[4]

- The enduring gratitude of the Osage people is still displayed in a thirty-six foot tall stained glass window in the Immaculate Conception Catholic Church in Pawhuska Oklahoma. This image shows the priest ministering to a group of prominent tribal members.

- Today a high percentage of the Osage people remain Roman Catholic. Many of those still practice a blended version of Catholicism and Osage tradition.

Some Reference Information:

1. Follow This Link for Chapter 5 of Our Story, The Catholic Osage Mission. This link also has four sub-chapters that provide detail about the mission and buildings (including this sub-chapter).

2. Follow This Link for more information about the Osages departure from Kansas, including the treaties and treaty demands regarding Father Schoenmakers gifted land. The section of land provided as a gift now makes up most of St. Paul, Kansas.

1. Follow This Link for Chapter 5 of Our Story, The Catholic Osage Mission. This link also has four sub-chapters that provide detail about the mission and buildings (including this sub-chapter).

2. Follow This Link for more information about the Osages departure from Kansas, including the treaties and treaty demands regarding Father Schoenmakers gifted land. The section of land provided as a gift now makes up most of St. Paul, Kansas.

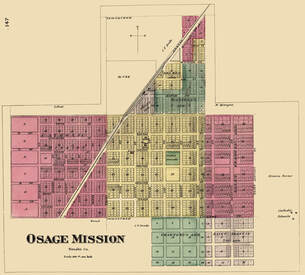

Most of St. Paul sits on the land the Osages gifted to Fr. Schoenmakers. Much of the area at left, in red, was never developed. (Click to enlarge)

Most of St. Paul sits on the land the Osages gifted to Fr. Schoenmakers. Much of the area at left, in red, was never developed. (Click to enlarge)

3. The section of land Fr. Schoenmakers was given is the section that most of St. Paul, Kansas occupies. When you think about it, we owe the Osages a huge debt of gratitude in return. Without that gift, our town probably would not exist, at least as it is today. Many of the families who formed here since the late 1800's would not exist. In fact, I probably would not be typing this now. My family is one of those families.

Follow This Link for more information about the founding of the town of Osage Mission, Now St. Paul.

4. {šǫmįhka (variants šǫmįʾhke, šǫmį'hka)} [After an early Catholic missionary named Father Schoenmakers] —a partial definition from the Osage Language Dictionary.}

5. Louis Burns compared the perils and trials of the Osage with the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in the Book of Revelation. Follow this link for more information about the early days at Osage Mission - Progress and Tragedy. https://www.acatholicmission.org/6-progress-and-tragedy.html

Follow This Link for more information about the founding of the town of Osage Mission, Now St. Paul.

4. {šǫmįhka (variants šǫmįʾhke, šǫmį'hka)} [After an early Catholic missionary named Father Schoenmakers] —a partial definition from the Osage Language Dictionary.}

5. Louis Burns compared the perils and trials of the Osage with the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in the Book of Revelation. Follow this link for more information about the early days at Osage Mission - Progress and Tragedy. https://www.acatholicmission.org/6-progress-and-tragedy.html